A recent pilgrim recounts some of his impressions coming home from walking 1,000 miles on the Camino de Santiago.

I begin with the end. Just after I got into the car, there was a crash. I had finished my pilgrimage two days before this, on the Feast of All Saints, and then on All Souls Day I had explored the rainy city of Santiago de Compostela. Now on this morning, November 3rd, a generous pilgrim friend was waiting for me with his car in the 5:45AM mist. I buckled into the passenger seat and showered him with muchísimas gracias. “It is not at all problem for me,” he assured me. Then he pulled out into the quiet street and began weaving through the damp city. That’s when the collision happened. “Whoa! Whoa!” I shouted to myself, gripping the overhead handle. I say there was a crash right then because that is how it felt. The impact of even being in a moving vehicle was violent and jarring.

I hadn’t moved faster than a walk for two and a half months. Since August, if I couldn’t go by foot, I didn’t go. It was November now, and in the car I was bolting past trees and benches and statues and pedestrians-turned-to-statues by our blistering speed of 40MPH. It felt sudden, exhilarating, dangerous, and alien. It felt almost unfair, like something the world would get carried away with if it weren’t careful. When we got on the highway, I actually had to close my eyes and put my head down to fend off the dizzies. We pulled into the airport. In less than 25 minutes we had covered a distance that would have taken us pilgrims two full days by foot. That very afternoon I would land in Barcelona, traveling in two hours over the same terrain most guidebooks recommend nearly forty days for walking. In medieval times, a pilgrim could expect his journey to last a year or two, and then he would still have to walk home.

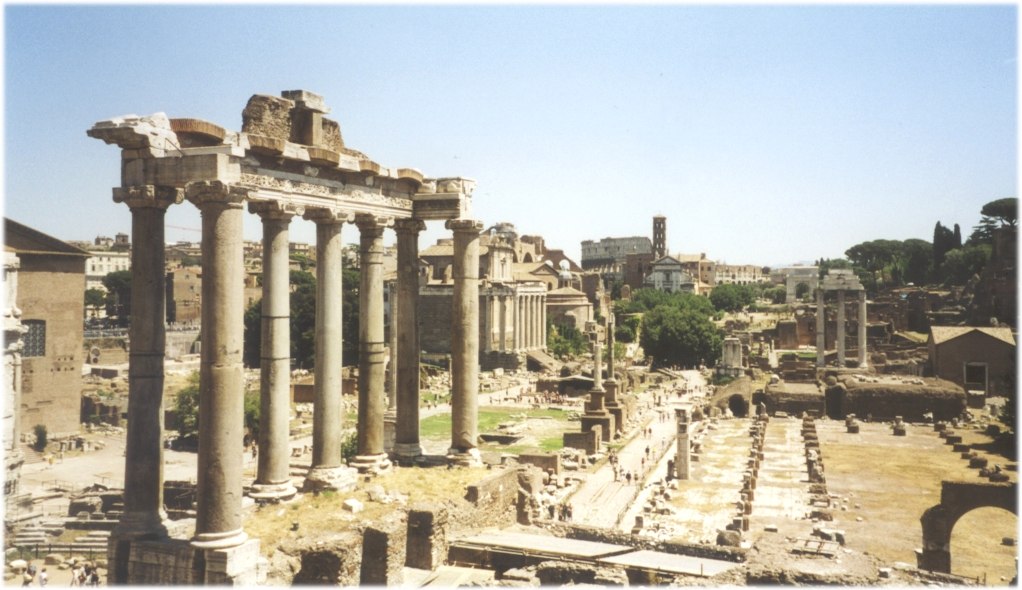

El Camino de Santiago. Jakobsweg. Le Chemin de Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle. The Way of St. James. In whatever language, this title refers to an ancient pilgrimage to the tomb of St. James the Apostle in the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, an old city in Northwest Spain. The earliest records indicate pilgrim activity before the turn of the first millennium. In the Middle Ages, many thousands of people from all over Europe—including both Charlemagne and St. Francis—would undertake the journey to visit the Apostle. In the centuries that followed, the Camino fell in and out of use, but recently the Way has seen a great resurgence. Last year roughly 215,000 people were received at the pilgrim office in Santiago de Compostela. Men and women from all over the world—from New Zealand to Korea to Brazil to Iceland to Spain—are hearing and answering the call of St. James.

I chose to begin my journey in Arles, France for several reasons, not the least of which was a desire to see the lands and colors that surrounded Vincent van Gogh in the final years of his life. And sure enough, I walked out of Mass that first morning and soon found myself in a field of dying sunflowers. I remember thinking that I had no idea what to think. Coming from a life in New York City, I entered the texture of the Camino like a bullet fired into water. But then, two months and one thousand miles later, the Camino ended, and I was taken out of the water and loaded back into the barrel of the modern world.

The world moves fast. The Camino slows you down. Physically, walking the Way bestows a lost dignity, making your own body the measure of the pace at which you move through the world. You wake up in one place, and if you wish to go anywhere that day, let alone end somewhere else that evening, your body must be the thing to take you there. If you get a blister—there will be blisters—you will get there slower. If you are sick, you may not be able to walk at all. Or maybe it’s a hot day, so along the way you rest under a chestnut tree and take off your socks to cool your feet, but then accidentally set your heel down on a dried chestnut burr. Each day is deeply related to the present condition of your body and environment, in a way that the modern world does not require or even allow. You become aware of your body’s deficiencies and yet proud of its responses, finding in your physical form a sensitivity to the scale of nature and a kind of ancient intuition. It is a bit like how you used to move as a child, buzzing around, when you weren’t self-conscience of your body but didn’t take it for granted either.

I didn’t fully appreciate this until my “car crash,” being hurled down the highway towards the airport in a metal box. From that moment, it was as if the world was saying to me, “Aw, you have a body? Let me help you with that.” There was an escalator up to the check-in counter, a conveyer belt to the boarding gate, a shuttle bus to the airplane 200 yards away. Then there was the plane, train, bus, and car that would take me home, where it would be possible to do everything I needed to do in a day without walking so much as five total minutes. Bill Bryson, in the book about his experience on the Appalachian Trail, astounds himself to calculate that every fifteen minutes he walked a greater distance than the average American walks in a week. It seems our civilization is set up to make walking as a means of transportation as difficult as possible, relegating it to recreation or leisure. To accomplish even part of your day’s tasks by foot is considered a luxury for the city dweller, and yet the pace of life is nowhere as fast as it is in the city.

Coming from the Camino, it was particularly easy to experience how life today has lost much of its connection to “creaturely rhythms,” to borrow a phrase from Wendell Berry. The modern world’s rhythms are primarily economic, mechanical, and industrial. The sounds alone can convey this: for seventy days I had heard cowbells, hawk cries, rustling vineyards, faint singing in the distance, church bells, footsteps, my own breathing, but I returned home to car horns, idling engines, trains rattling, heating units clicking, sirens blaring, phones ringing, electronics humming. “The rhythms of the creaturely world are living, sensitive, responsive, and under influence,” says Berry. A walk around the park—not the half-run down the steps as the subway screeches into place—is our little attempt to remember this forgotten rhythm, trusting that it’s alright not to get somewhere faster than your body can take you. For almost all of human history, with the occasional help of a ship or animal, a person had to live by this limitation.

Of course, walking the Camino is not the only way to find a slower pace. You could hike the Pacific Crest Trail, juice fast in Woodstock, or dig for arrowheads in Maine. But the Way of Saint James is unique for one enormous reason: it is a pilgrimage first and foremost. The spirit of St. James is everywhere and in everything. Whatever varied reasons one might have for beginning the walk, there is a very clear and definite sense that it is a shared journey to something. I remember after communal dinner at one of the parish pilgrim shelters, we all sat in the choir loft of the adjoining church with a few lit candles. A middle-aged Korean man who spoke patchy English was moved to tears trying to describe how it felt to have something so large in common with people from all over the world. He was talking about St. James. The scallop-shell symbol of the pilgrimage reveals this communal reality, with its many lines that begin far apart and all converge on a single point.

“We are pilgrims on the earth and strangers,” says Vincent van Gogh, who was a preacher before he was a painter. In his first Sunday sermon in 1876, he explained, “[W]e come from afar and we are going far. The journey of our life goes from the loving breast of our Mother on earth to the arms of our Father in heaven. Everything on earth changes—we have no abiding city here—it is the experience of everybody.” Capturing the spirit of the St. James, he exclaimed, “Ah, indeed we only pass through the earth, we only pass through life, we are strangers and pilgrims on the earth.”

The Camino helps us believe this. I remarked before that the Camino slows things down, which is true. But in another respect, the Camino speeds things up. Have you ever seen a time-lapse video of a plant growing? In a matter of seconds you can see its whole life, from sprouting to growing leaves to flowering to wilting. It unlocks a secret coherence of the plant that is impossible to see otherwise, one stage at a time. Or similarly, maybe you watched the slideshow at your grandparents’ 50th wedding anniversary, which tells the story of their whole life by focusing on a few choice moments, representing in minutes what decades have spread apart.

Walking the Camino is a bit like these two things. The Camino is a little life. It is complete with beginning, middle, and end. Its context as a pilgrimage powerfully unites spirit and body. It has a wholeness about it, pulling together in a brief amount of time many characteristics of what life itself is. The Way is so beautifully balanced: aloneness and society, food and hunger, song and silence, nature and city, past and present, trials and rewards, doubts and purpose. It simplifies and highlights. The exhausting scale of all possible things is narrowed down to a significant but manageable chunk, clarifying what is and what is not in your control. The small details and the big picture are seamlessly integrated. You kneel down to tie your shoe and stand up to glimpse the Pyrenees. It is not more real; you just pay closer attention. Countless people have done it before you, and countless more will do it after. We are allowed to see that, in van Gogh’s words, “We only pass through the earth, we only pass through life.”

But like all pilgrimages, mine eventually came to an end. After my jolting car ride, I was dropped back into the modern world at the Santiago airport. Reporting to the Ryanair check-in, I gave my passport and reservation number.

“Do you have your boarding pass, sir?”

“Uh, no? Aren’t you supposed to give me that? And anyway I didn’t really have access to a printer, let alone computer. I’ve been walking the Cam…”

“We can print it for you for a small fee. That will be 17 euros sir.”

“Well, that seems a little unfair, 17 euros. I just…”

“You must have misheard me sir. I said 77 euros. You can pay behind you. Come back to this line once you’ve paid.”

Of all the things that flashed through my mind, most of them unprintable here, I remembered something an older pilgrim had said to me a few days earlier over a beer: “Good luck on the real Camino.” He meant life, and he was right. So I paid the fee and walked onward. A few minutes later, muttering to myself while going through security, I heard in the distance a young man yell, “77 euros?! What the &%@$ is wrong with you people!” Without the spirit of the Camino, that would have been me. But my challenges were not over yet. Following the boarding-pass debacle, another airline would lose my bags on the way to New York. And my phone would get wet in the rain, frying it and costing me every picture I had taken on the trip. I arrived at JFK swindled, with no phone, no photos, and no bag. Welcome to the new Camino.

The world is notorious for fragmenting life, for bombarding our attention, for stacking worry on worry over too many things that matter too little. A Camino friend told me that after arriving home, he was overwhelmed by how, no matter how much he did in a day, it always felt like it wasn’t quite enough. Against this anxious scattering, we do all kinds of things that recollect. We grab a drink after work with friends, build a snowman with our kids, bike to yoga, read a favorite book, hunt for mushrooms, go to church. We try to hold onto one little piece at a time of the massiveness that we have to be thankful for. The pilgrim feels this acutely. He wrestles to hold onto what the Camino gave him, above all that spirit of gratitude, which forces him to admit that he has nothing that he has not received. As T.S. Eliot would put it, “For [him] there is only the trying. The rest is not [his] business.”

At the time of writing this, it has been four months now since I finished that pilgrimage, four months since I began this new one. Though I still actively fight against it, I have to admit that the feeling of being in a car isn’t so dizzying anymore. But it still does—and hopefully will always—feel like an exception to me. I have taken up cross-country skiing, but no matter how often I get out, my body is putting back on a soft edge. The callouses on my feet and hands are gone. A few off-color patches remain where blisters were, memories of toughness or pain. Some days, especially difficult ones, I say the St. James prayer that I said daily on along the Way: “O St. James, show us pilgrims, one step at a time, the hopeful happy way that leads to Him.” Tomorrow still feels like a town I am going to but know nothing about.

If you start painting your apartment and forget to open a window, the fumes fill the room and make you dizzy. As you paint, though, you smell it less and less, growing accustomed to the contaminant. Only when you have to run out to your neighbor’s to get some tool you need, where you chat and have a drink, do you come back and smell paint again. Walking the Camino is like visiting St. James’ home in the sky for a while, to get some things you need, drinking his wine and breathing fresh air. When you come back to your life, you smell paint again, open a window, and know you still have work to do.