Another week, another episode of the mini-series The Bible. These are my first impressions of the second episode.

Another week, another episode of the mini-series The Bible. These are my first impressions of the second episode.

The pacing, redux. The second episode is 86 minutes long, and the first six minutes consist of footage from the first episode, so that leaves only 80 minutes for the second episode to take us all the way from the spies in Jericho to the birth of King Solomon — a period that covers about two or three centuries.

Each episode so far has begun with a title card proclaiming that this mini-series is true to the “spirit” of the Bible, but the more this show zips through the Old Testament, the more I wonder how accurate this claim can possibly be.

For one thing, there are all the really important stories that the mini-series seems to be skipping entirely, like the ones about Job and Ruth. More importantly, though, there are tensions and even contradictions within the Old Testament — and sometimes within the very same text! — that are squelched entirely as this series rushes from one quick battle scene to the next.

For example, in Deuteronomy 24, Moses says parents should not be put to death for the sins of their children, and children should not be put to death for the sins of their parents — each generation will pay for its own sins and no others — but in Deuteronomy 25, just one chapter later, Moses commands future generations of Israelites to wipe out the Amalekites for the sins of their ancestors. And, as it happens, this last command becomes a key plot point in this week’s episode, when Samuel orders Saul to obliterate the Amalekites and condemns him for failing to do a thorough job of it.

Or consider how Deuteronomy 23 says that no descendant of a Moabite or Ammonite may enter the assembly of the Lord, “not even in the tenth generation” — a law that was ruthlessly enforced centuries later by Ezra and Nehemiah — whereas the book of Ruth not only celebrates a Moabite woman’s marriage to an Israelite man, but ends with the possibly startling revelation that King David was her descendant, and was indeed only three generations removed from her.

(Note, too, incidentally, how the passage from Deuteronomy bars not only foreigners from the assembly of the Lord but eunuchs, too; and note how Isaiah 56 seems to counter this by welcoming both eunuchs and foreigners into the Temple. And note, too, that it is this Isaiah passage which Jesus is quoting, centuries later, when he “cleanses” the Temple and calls it “a house of prayer for all nations.”)

Different religious traditions have different ways of dealing with these tensions, but they’re there in the text, and any representation of the text that claims to be true to the “spirit” of the text should probably try to address that somehow. But no, this mini-series has little interest in any sort of intentional ambiguity, or indeed in anything that would get in the way of making these stories “exciting”, and so it blitzes right past all that stuff.

The violence, redux. There’s a lot more hacking and slashing in this episode than there was in the previous one, but it doesn’t seem so gratuitous this time, if only because the stories of Joshua, the Judges and the early Kings are indeed largely concerned with the wars fought between the Israelites on the one hand and the neighbouring nations on the other hand. (The Bible also talks about civil wars between the Israelite tribes, but the mini-series skips over those.)

Even so, as justified as the violence might be, the mini-series does ramp things up a bit.

Last week, I mentioned the gratuitous swordfight between Joshua’s spies and the inhabitants of Jericho; this week’s episode continues with the Israelite spies invading Rahab’s house and holding a sword to the throat of her child in order to keep Rahab quiet. And then the spy goes on to say that God “saved us from slavery. We are his chosen.”

Last week, I mentioned the gratuitous swordfight between Joshua’s spies and the inhabitants of Jericho; this week’s episode continues with the Israelite spies invading Rahab’s house and holding a sword to the throat of her child in order to keep Rahab quiet. And then the spy goes on to say that God “saved us from slavery. We are his chosen.”

Now how would you react if someone invaded your home, threatened your child and then said he was on a mission from God? At times you wonder if the makers of this series are actually trying to make the Israelites look like villains.

I think there’s another explanation for this, though. In the Bible, Rahab is a prostitute and the spies “stay” at her house before the king of Jericho sends soldiers looking for them. What the spies actually do in Rahab’s house, we are not told — but it doesn’t necessarily look all that good.

So, apart from the fact that the filmmakers wanted to keep things “exciting”, I think they were also trying to find a way to explain how the spies got inside Rahab’s house without suggesting that there was anything untoward about their arrival there. Better, apparently, to say that they were running from a swordfight — and holding Rahab’s family hostage — than to say that they might have paid her for sex.

The mini-series goes further than the Bible in depicting divinely-sanctioned violence in other ways, too.

In Judges 16, when Samson is about to knock down the pillars of the Philistine temple, thereby killing both himself and the thousands of Philistines who have gathered to mock him there, Samson directs all his words at God and asks God for the strength to get his revenge; but in the mini-series, Samson directs his words at the Philistines and taunts them by saying that God “wants me to destroy you all!”

In Judges 16, when Samson is about to knock down the pillars of the Philistine temple, thereby killing both himself and the thousands of Philistines who have gathered to mock him there, Samson directs all his words at God and asks God for the strength to get his revenge; but in the mini-series, Samson directs his words at the Philistines and taunts them by saying that God “wants me to destroy you all!”

Then there is the bit where David brings Saul a bag full of Philistine foreskins, and Saul asks, “From a hundred men?” and David replies, “Two hundred. God was with me.” This is a reasonable extrapolation from I Samuel 18, where David’s general success in battle is taken by Saul as a sign that “the LORD was with David”, but it is not something that David himself claims, at least in this particular context.

It is also interesting to hear Uriah tell David that the reason he won’t go back to his house and sleep with his wife, after David calls him back from the battlefront, is because the war he and his fellow soldiers are fighting is a “holy war”. That isn’t quite the reason he gives in II Samuel 11.

Prostitution. I have already noted how this episode downplays the idea that Joshua’s spies might have sought the services of a prostitute. I can’t help noting that the episode mitigates this theme in other ways, too.

First, it’s not even clear that the Rahab of this mini-series is a prostitute. She is accosted by a man in the street who calls her “my little whore”, but the impression one gets is that she is, at most, the victim of a sexual aggressor. What the text treats as a matter-of-fact description of her profession becomes just an insult uttered by some bit player.

Second, the episode completely omits Samson’s visit to a prostitute in Gaza. His visit there led to an almost-confrontation with the local Philistines which culminated in one of Samson’s more impressive feats of strength, but the mini-series skips this entirely, thereby allowing us to think that Samson’s later dalliance with Delilah was a one-time display of weakness, rather than part of a recurring pattern.

Nationalism. Last week’s episode ended with Joshua’s spies crying “For Israel!” as a swordfight began in the streets of Jericho. That moment is repeated at the beginning of the second episode, and, interestingly, it is also echoed in a scene set a couple centuries later, when David and his men capture Jerusalem.

I am also struck by how, when Joshua conquers Jericho, the Israelites around him began to chant “Israel! Israel! Israel!” Echoes of how modern Americans chant “U.S.A.! U.S.A.! U.S.A.!” perhaps? I can’t help thinking that the ancient Israelites would have been likely to chant something a little more theologically inflected, but I could be wrong about that.

Note, too, how enthusiastic the Israelite leaders are in their calls to subjugate the other nations. When the walls of Jericho fall, Joshua cries, “We give this city to the Lord! Destroy everything!” And when David kills Goliath, King Saul tells his soldiers to attack the Philistines, and cries, “Let us make slaves of them!”

This is not an inaccurate depiction of how the Israelites and other nations of that era would have dealt with each other. But it is also the sort of thing that other Bible movies would try to get around, somehow, either by toning it down or making it clear that the other nations had earned such treatment. It is striking that The Bible doesn’t go either route, despite the fact that it is trying to popularize the Bible for a mass audience.

Continuity between Bible stories, redux. In addition to the two “For Israel!” scenes, this episode includes a bit where Jonathan says he loves David, and Saul tries to dampen this by saying, “As Abel no doubt once loved Cain.”

Continuity between Bible stories, redux. In addition to the two “For Israel!” scenes, this episode includes a bit where Jonathan says he loves David, and Saul tries to dampen this by saying, “As Abel no doubt once loved Cain.”

What’s interesting about this particular reference to an earlier Bible story is that Saul is actually wrong to draw the parallel that he does. All of the other references to earlier Bible stories have maintained some sort of continuity between them — God made a promise to Abraham, and now it is being fulfilled by Moses, etc. — but here there is no parallel at all between the genuine, mutual love between Jonathan and David on the one hand and the fratricide that Cain commits against Abel on the other hand.

Ethnicity. I devoted an entire blog post two months ago to the fact that Samson, unlike virtually every other Israelite character in this series, is portrayed by a black actor. Now that I have seen the episode itself, I don’t think we can chalk this up to “colour-blind” casting.

For one thing, you can’t help but wonder if there is a certain amount of racial stereotyping involved in the fact that the mini-series’ only significant black character (not counting his mother, who is family after all, or a couple of the angels, who aren’t even human) happens to be the one biblical character who is best-known for his brute strength.

But the mini-series also grossly oversimplifies the story of Samson — and plays on modern racial subtexts — by suggesting that Philistine antagonism towards him was racism pure and simple. When (black) Samson marries his (white) Philistine wife, a Philistine villain in the background declares, “We need to send these Israelites a message, make it clear to them they cannot take our women. Our people should never mix.”

Oversimplification. In the Bible, Samson’s interactions with the Philistines are a long, complicated affair (or series of affairs, considering his penchant for Philistine women). But virtually all of the detail that makes these interactions interesting is left out of the episode altogether.

Oversimplification. In the Bible, Samson’s interactions with the Philistines are a long, complicated affair (or series of affairs, considering his penchant for Philistine women). But virtually all of the detail that makes these interactions interesting is left out of the episode altogether.

Take Samson’s wedding. In Judges 14-15, Samson gives his guests a riddle to solve, and they pressure his wife into getting the answer from him. Samson reacts by killing a bunch of Philistines and abandoning his wife, but when he tries to get her back, he is told that she has been given to another man. So then Samson destroys the Philistines’ wheat fields and vineyards, after which the Philistines get their own revenge by killing Samson’s wife and her father.

This cycle of violence (and betrayals) is completely written out of the mini-series, so that Samson’s wife and father-in-law are now murdered almost immediately after the wedding, simply because she married someone of the wrong race.

Then there is Samson’s relationship with Delilah. In Judges 16, Delilah asks Samson for the secret of his strength multiple times, and, like an idiot, he doesn’t give her the correct information until after she has demonstrated — twice! — that she is willing to use the information against him. In the mini-series, however, Samson gives her the correct answer the first time she asks.

Banal or problematic dialogue. David tells Saul he didn’t sneak up on Saul and kill him, even though he could have, because “only evildoers do evil deeds.” In the hands of better filmmakers, I would think that the mini-series was going to challenge this idea, given David’s later actions (especially in the Bathsheba affair). But I’m not sure the makers of this series were thinking that far ahead; instead, it sounds like just another trite would-be truism.

Banal or problematic dialogue. David tells Saul he didn’t sneak up on Saul and kill him, even though he could have, because “only evildoers do evil deeds.” In the hands of better filmmakers, I would think that the mini-series was going to challenge this idea, given David’s later actions (especially in the Bathsheba affair). But I’m not sure the makers of this series were thinking that far ahead; instead, it sounds like just another trite would-be truism.

Also, when the Philistine leaders first approach Delilah to ask her to betray Samson, she protests, “He’s changed! He’s a different man since he met me!” Again, quite apart from the fact that we barely spend enough time with Samson to actually notice any changes, something about the wording here seems a little off, a little anachronistic, to me.

Minor quibbles. The angel who appears to Joshua tells him, “The Lord parted the waters for Moses. For you, he will split rock.” Actually, by this point in the story, the Lord had already parted — or at least blocked — the waters for Joshua, too.

Minor quibbles. The angel who appears to Joshua tells him, “The Lord parted the waters for Moses. For you, he will split rock.” Actually, by this point in the story, the Lord had already parted — or at least blocked — the waters for Joshua, too.

It’s also interesting how the mini-series amplifies the part of Samson’s mother — even allowing her to search through the rubble of the Philistine temple after Samson dies — while completely ignoring his father and other kinsmen.

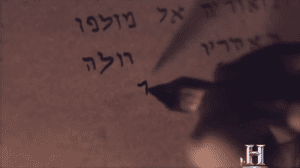

And is David really writing that letter to Joab in modern Hebrew? Click here to see the sort of alphabet David or his scribes would have really used back then.

And is David really writing that letter to Joab in modern Hebrew? Click here to see the sort of alphabet David or his scribes would have really used back then.

Things I liked. As rushed as things might be in this mini-series, the jump cut from young David fighting Philistines to the older David fighting Philistines was actually quite effective, and neatly sums up the fact that, yup, David did a lot of fighting.

I also liked the way Saul gets the line about David slaying “thousands”, and the way his son Jonathan gets the line about David slaying “tens of thousands”. The way it’s played here, the extra praise for David doesn’t seem like it should have been anywhere near as threatening as Saul makes it out to be, which just underscores the fact that Saul, in his paranoia, was out of sync with his own family.

I also get a kick out of the fact that the prophet Samuel is played here by Paul Freeman, who may be best known to movie buffs as Belloq in Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), i.e. the rival archaeologist who dresses up as a high priest and opens the Ark of the Covenant, after which his head explodes.

I also get a kick out of the fact that the prophet Samuel is played here by Paul Freeman, who may be best known to movie buffs as Belloq in Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), i.e. the rival archaeologist who dresses up as a high priest and opens the Ark of the Covenant, after which his head explodes.

For a Bible-movie buff like me, it is kind of fun to note that Freeman previously played Cornelius — the first Gentile convert to Christianity — in the mini-series A.D. Anno Domini (1985), and that the apostle Peter, who baptizes Cornelius, was played in that mini-series by Denis Quilley, who also played Samuel in Bruce Beresford’s King David (1985). So from now on, whenever I see Peter meet Cornelius in A.D., it will be like watching a meeting of Samuels.

Here endeth my post on episode two. Episode three — which will finish the Old Testament section of the mini-series and begin the New Testament section — airs Sunday night.