Three down, two to go! Here are my first impressions of the third episode of The Bible, which ended the Old Testament section of the mini-series and began the New Testament section.

Three down, two to go! Here are my first impressions of the third episode of The Bible, which ended the Old Testament section of the mini-series and began the New Testament section.

Continuity between Bible stories, redux. For all my grumbling about the series to date, there is one thing about it that I have always appreciated, and that is the way it links the various Bible stories, whether by having characters in one story recall what their ancestors did in another, or by having the angels appear in multiple stories wearing the exact same clothes, etc. And the first half of this episode is seriously impressive on that level.

For one thing, it depicts the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians, which very few filmmakers have ever done; indeed, apart from Jeremiah (1998), one of the films in ‘The Bible Collection’, I can’t recall ever seeing this event dramatized before. So that alone makes this episode somewhat exceptional.

But even more impressive is the way this episode weaves together the various bits in the Bible that are connected to the fall of Jerusalem. The episode begins with the prophet Jeremiah warning King Zedekiah not to rebel against the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar, so at first we experience the fall of Jerusalem from Jeremiah’s point of view. But then we see Daniel and his friends captured by the Babylonians. And then we see Zedekiah captured by the Babylonians, and forced to watch as his sons are killed (after which his eyes are put out, so that the death of his sons is the last thing he will ever see).

But even more impressive is the way this episode weaves together the various bits in the Bible that are connected to the fall of Jerusalem. The episode begins with the prophet Jeremiah warning King Zedekiah not to rebel against the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar, so at first we experience the fall of Jerusalem from Jeremiah’s point of view. But then we see Daniel and his friends captured by the Babylonians. And then we see Zedekiah captured by the Babylonians, and forced to watch as his sons are killed (after which his eyes are put out, so that the death of his sons is the last thing he will ever see).

And then we’re back to Jeremiah as he “escapes” to Egypt — though the series glosses over the fact that Jeremiah was actually treated fairly well by the Babylonians, and was only taken to Egypt against his will after some of his fellow Judeans murdered the man who had been put in charge of the country following Zedekiah’s defeat. In fact, Jeremiah believed that going to Egypt was anything but an escape, because he believed Nebuchadnezzar would attack Egypt next and deal harshly with everyone he found there.

But never mind that right now; a lot of details are bound to go missing when a mini-series rushes through events as quickly as this one does. Heck, never mind the fact that Daniel was actually taken from Jerusalem the first time Nebuchadnezzar attacked the city, about two decades earlier, during the reign of Zedekiah’s brother Jehoiakim. I’m just glad to see the fates of Jeremiah, Zedekiah and Daniel linked like this. Among other things, seeing Nebuchadnezzar’s brutal treatment of Zedekiah lends a menacing subtext to his dealings with Daniel later on — a subtext that is not always quite so explicit in stand-alone adaptations of the Book of Daniel.

But the continuity doesn’t stop there. Daniel and his three friends recite biblical Psalms when they pray; and then, when Daniel’s friends are thrown into the fiery furnace, we get another possible “Christophany” as a fourth man appears in the flames with them; and then, as Daniel’s story comes to its conclusion, he tells one of his friends about a dream he had, in which he caught glimpses of the future, including Roman soldiers (he doesn’t call them that, but we recognize the accompanying visual).

But the continuity doesn’t stop there. Daniel and his three friends recite biblical Psalms when they pray; and then, when Daniel’s friends are thrown into the fiery furnace, we get another possible “Christophany” as a fourth man appears in the flames with them; and then, as Daniel’s story comes to its conclusion, he tells one of his friends about a dream he had, in which he caught glimpses of the future, including Roman soldiers (he doesn’t call them that, but we recognize the accompanying visual).

What’s more, Daniel tells his friend he saw “one like a son of man coming on the clouds” — a prophecy that many Christians take to be a reference to the second coming of Jesus, but which the mini-series treats as though it were a reference to his first coming.

And so the series no longer just has flashbacks to the earlier Bible stories; it has flash-forwards as well. And with that, it segues into the New Testament quite nicely.

(Come to think of it, what’s impressive here is not just the continuity between different Bible books, but the continuity within the Book of Daniel itself. The first six chapters are basically narrative, and have provided fodder for many children’s books over the years, but the last six chapters are a collection of prophecies, and are very popular with end-times enthusiasts and the like. In pop-culture terms, it’s rare to see those two parts of the book brought together like this, so that, itself, is something to commend the mini-series for.)

Prophecies. There are at least two other flash-forwards in this episode. In one, Joseph has a dream about the slaughter of the innocents, which prompts him to take Mary and Jesus out of Bethlehem.

And then there is a fascinating bit during Jesus’ temptation in the wilderness, where Satan’s offer of political power — complete with Pontius Pilate bowing before Jesus and kissing his feet — is cross-cut with footage from one of the later episodes, in which the Romans abuse Jesus. Other Jesus movies have emphasized the political, even militaristic, aspect of Satan’s offer here (see, e.g., The Miracle Maker), but I can’t recall another film that makes it so personal, or ties it so directly to the actual fate that awaited Jesus.

And then there is a fascinating bit during Jesus’ temptation in the wilderness, where Satan’s offer of political power — complete with Pontius Pilate bowing before Jesus and kissing his feet — is cross-cut with footage from one of the later episodes, in which the Romans abuse Jesus. Other Jesus movies have emphasized the political, even militaristic, aspect of Satan’s offer here (see, e.g., The Miracle Maker), but I can’t recall another film that makes it so personal, or ties it so directly to the actual fate that awaited Jesus.

On a quasi-related note — nothing to do with flash-forwards, but very much to do with prophecies — there is an intriguing bit of dialogue, after the Persians conquer the Babylonians, in which Daniel tells the Persian king Cyrus that his victory was foretold by “a prophet here in Babylon, Isaiah.”

Does this mean the mini-series subscribes to the view — widely accepted among academics, but frowned upon by some old-school inerrantists — that the later portions of the Book of Isaiah, including the prophecy about Cyrus in Isaiah 44-45, were written not by the Isaiah who lived in the 8th century BC, but by the so-called “Deutero-Isaiah” who lived in the 6th century BC? Sounds like it.

This reminds me of an interesting last-minute tweak that Mel Gibson made to The Passion of the Christ (2004). The film begins with a quote from Isaiah 53, and in the workprint that I saw at a church-based screening several weeks before the film came out, the quote was dated to about 400 BC — but when the final version of the film came out in theatres, the date had been changed to 700 BC. I have sometimes wondered if Gibson made the change because the conservative pastors to whom he was promoting his film objected to the scholarship that lay behind the original date, but that’s just a guess on my part.

In any case, it’s interesting to see this mini-series go the other way.

Other prophecies are treated in a more conventional manner. One of Herod’s scribes cites a prophecy that is actually a pastiche of Isaiah 7:14 and 9:6, and uses the word “virgin” where the more accurate translation of the original Hebrew would be “young woman”. As N.T. Wright and others have noted, no one interpreted this passage as a prediction of the messiah’s virginal conception until the author of Matthew did, so the words spoken by Herod’s scribe here are somewhat anachronistic.

The episode also suggests that the magi who paid homage to the newborn Jesus were conversant in the Hebrew scriptures, since one of them quotes the line in Numbers 24 about “a star coming out of Jacob” as though it were a literal prediction of the literal star that the magus in question is looking at.

The episode also suggests that the magi who paid homage to the newborn Jesus were conversant in the Hebrew scriptures, since one of them quotes the line in Numbers 24 about “a star coming out of Jacob” as though it were a literal prediction of the literal star that the magus in question is looking at.

But presumably he would not have read the rest of the passage so literally, since it goes on to talk about the star and its accompanying sceptre crushing the foreheads and skulls of Israel’s enemies. Some have argued that the prophecy actually refers to David, and of course the messiah has always been understood as a “type” of David, but it’s difficult to apply this prophecy to Jesus directly, at least in any sort of literal manner.

The violence, redux. Once again, the mini-series just can’t resist the urge to pump up the violence at every opportunity.

This is less of an issue in the first half, which is, of course, all about the wars and abuses of power committed by the kings of Babylon and Persia — though once again, it must be said that the makers of this mini-series do tend to dwell on the violence a little much.

But it doesn’t really become a problem until the second half of the episode, when our focus turns to the New Testament and practically the first thing we see is a small group of Jewish rebels getting into a fight with King Herod’s men, and then Herod himself stabbing one of these rebels in the neck and letting him bleed to death. (None of these details are actually from the New Testament itself; instead, they come from Josephus’ history of the period.)

But it doesn’t really become a problem until the second half of the episode, when our focus turns to the New Testament and practically the first thing we see is a small group of Jewish rebels getting into a fight with King Herod’s men, and then Herod himself stabbing one of these rebels in the neck and letting him bleed to death. (None of these details are actually from the New Testament itself; instead, they come from Josephus’ history of the period.)

This is followed by the Annunciation, which takes place when Mary is trying to get away from a fight between Romans and her fellow Nazarenes. That’s right, the voice of Gabriel plays on the soundtrack as we see slow-motion shots of people being beaten up.

Later, of course, there is the slaughter of the innocents, which we see twice: once in Joseph’s dream, and once when it actually happens. This is followed by a scene in which Herod kills his eldest son, and then by a sequence in which the Jews respond to news of Herod’s death by rising up against the Romans and are then immediately crushed for their efforts.

And then, at the end of the episode, the bit where Jesus calls on Peter to become his first disciple is cross-cut with footage of John the Baptist yelling proclamations in prison just prior to getting his head chopped off.

And then, at the end of the episode, the bit where Jesus calls on Peter to become his first disciple is cross-cut with footage of John the Baptist yelling proclamations in prison just prior to getting his head chopped off.

Most of the violent acts depicted here can certainly be justified as biblical and/or historical, but the problem is how the mini-series consistently relies on this violence to keep things interesting — which, inevitably and ironically, ends up making things kind of dull.

“God is with us.” Two weeks ago, I had some qualms about the way Moses said God was “with us” and therefore not with the Egyptians. Then, last week, I quibbled with the way David says God was “with me” when he killed hundreds of Philistines and took their foreskins.

But it’s becoming apparent that the phrase “God is with us” really is one of this mini-series’ central motifs. It is especially pronounced in Daniel’s ecstatic reaction to the miracle of the fiery furnace, where he repeats the words “with us” a few times. And the phrase gets an interesting new application when Daniel tells the Persian king Cyrus — who has just apologized for putting him in the lion’s den — “God is with you.”

Echoes and callbacks. Note how Jerusalem, under Zedekiah, resists the Babylonian armies for 18 months, leading to cannibalism within the city walls and mass slaughter once the Babylonians finally enter from outside. And then note how, in contrast, the Babylonians surrender to the Persian king Cyrus without a fight.

Note also how Daniel stands with his arms outstreched in the lion’s den, in a way that recalls the possible “Christophany” in the fiery furnace.

Note also how the episode includes two scenes of people in prison, or at least a prison-like structure, and how the episode drastically simplifies the stories of those people. On the one hand, there is Nebuchadnezzar, who goes insane — but there is no hint of how he regained his sanity and worshiped God for it. And on the other hand, there is John the Baptist, who spends his brief time in prison shouting that the messiah has come, without expressing any of the doubts that came to him after he had been locked up for a while.

Note also how the episode includes two scenes of people in prison, or at least a prison-like structure, and how the episode drastically simplifies the stories of those people. On the one hand, there is Nebuchadnezzar, who goes insane — but there is no hint of how he regained his sanity and worshiped God for it. And on the other hand, there is John the Baptist, who spends his brief time in prison shouting that the messiah has come, without expressing any of the doubts that came to him after he had been locked up for a while.

Finally, note how Jesus strides into the water at his baptism, and how he strides into the water again when he approaches Peter’s boat.

The meaning of Hebrew names. Nebuchadnezzar and his chariot driver share a chuckle over the meaning of the word “Jerusalem” — “city of peace” — as the Babylonian army embarks on its long journey to Judea.

More interestingly, the episode eschews the Babylonian names by which Daniel’s three friends are most commonly known. The Book of Daniel tells us, right at the beginning, that Daniel and his three friends were all given Babylonian names — but then it goes on to refer to Daniel mainly by his Hebrew name while referring to the others mainly by their Babylonian names Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego.

This mini-series is having none of that: instead, it has Azariah (the friend who was re-named Abednego) insist that he be known by his Hebrew name, which means “He who is held by God.” And it builds up the Daniel-Azariah relationship in a way that allows for some exposition, as well as an interesting reversal, wherein Azariah is forced to watch from the sidelines as Daniel is punished for his faith in God, just as Daniel had been forced some years earlier to watch as Azariah and the others were tossed into the fiery furnace.

This mini-series is having none of that: instead, it has Azariah (the friend who was re-named Abednego) insist that he be known by his Hebrew name, which means “He who is held by God.” And it builds up the Daniel-Azariah relationship in a way that allows for some exposition, as well as an interesting reversal, wherein Azariah is forced to watch from the sidelines as Daniel is punished for his faith in God, just as Daniel had been forced some years earlier to watch as Azariah and the others were tossed into the fiery furnace.

Cause and effect? After the fiery-furnace episode, the narrator states that the miracle there unites the Jewish people. Later, when Cyrus lets Daniel out of the lion’s den, the miracle prompts Cyrus to allow the Jews to return to Jerusalem.

The Book of Daniel itself never states that these miracles led to these consequences; in fact, it barely mentions Cyrus at all. (In the Bible, the king who throws Daniel in the lion’s den is not Cyrus, but a figure named Darius the Mede, who may have ruled Babylon on Cyrus’s behalf.)

The Book of Daniel itself never states that these miracles led to these consequences; in fact, it barely mentions Cyrus at all. (In the Bible, the king who throws Daniel in the lion’s den is not Cyrus, but a figure named Darius the Mede, who may have ruled Babylon on Cyrus’s behalf.)

But there’s something kind of clever about this, and you can see why the filmmakers made these connections. It works dramatically, and it is certainly a valid speculation if you regard the miracles as historical events (which of course many believers do).

In the case of the fiery furnace, however, the thrust of the biblical story is not so much that the Jewish people are united, but that the pagan king comes to believe in God — so much so that he threatens death and dismemberment to anyone who speaks against the Israelite God. (In a similar vein, the mini-series shows Cyrus — who has just declared his own belief in God — throwing Daniel’s accuser into the lion’s den for making a snarky comment about the Jews not having a temple of their own. In the Bible, the king went even further and killed the accusers’ wives and children.)

And of course, I’ve already noted that the mini-series omits the other occasion on which Nebuchadnezzar professes his faith in God, following his bout of insanity.

So once again, we may have evidence here of a tendency on the part of this mini-series to tilt its focus ever-so-slightly away from Israel’s God and onto Israel itself.

What is Jesus thinking? Several years ago, I wrote an essay on the use of flashbacks and point-of-view shots in Jesus films. One of the points of the essay was that filmmakers often use these “subjective” techniques to draw us into the mind of Jesus, and thus to help us experience his humanity even as the films ask us to behold his divinity.

The adult Jesus is only present for about the last 14 minutes of this episode, but it has a few interesting details that point towards a similar kind of balancing act. The first time we get a good look at Jesus’ face, it slowly comes into focus while John the Baptist prophesies his coming — that points to Jesus’ divinity. But then, when Jesus is baptized, we get a point-of-view shot looking up through the water at John — that points to Jesus’ humanity, and it underscores his humble submission to John’s baptism.

The adult Jesus is only present for about the last 14 minutes of this episode, but it has a few interesting details that point towards a similar kind of balancing act. The first time we get a good look at Jesus’ face, it slowly comes into focus while John the Baptist prophesies his coming — that points to Jesus’ divinity. But then, when Jesus is baptized, we get a point-of-view shot looking up through the water at John — that points to Jesus’ humanity, and it underscores his humble submission to John’s baptism.

This is followed by Jesus’ temptation in the wilderness, where, as I noted earlier, we get a mix of images, all representing Jesus’ thoughts: on the one hand, there are the glimpses of power that Satan is offering him, but on the other hand, there is the suffering he knows he will endure if he sticks to God’s plan for him. This, too, draws us into Jesus’ thoughts.

Finally, there is one “private” detail that I find kind of intriguing. The temptation sequence begins with Satan throwing a rock to Jesus, which he catches. Later, when Jesus approaches Peter’s boat, he picks up a rock and looks at it before putting it back down. What is he thinking? Is he pondering the choice he has made? Having refused to perform the miracle that Satan asked him to perform, is he looking ahead to his own first miracle? (The first miracle he performs in this mini-series, that is; according to John’s gospel, the first miracle he performed was changing water to wine.)

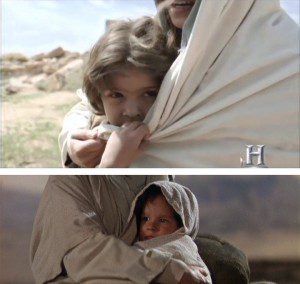

I also like the way the young Jesus peers over his mother’s shawl as she tries to shield his eyes from the sight of dozens of crosses. It’s kind of reminiscent of a bit from The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), where the eyes of young Jesus look at a road lined, similarly, with dozens of crosses. In both cases, you cannot help but wonder, What is he thinking?

I also like the way the young Jesus peers over his mother’s shawl as she tries to shield his eyes from the sight of dozens of crosses. It’s kind of reminiscent of a bit from The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), where the eyes of young Jesus look at a road lined, similarly, with dozens of crosses. In both cases, you cannot help but wonder, What is he thinking?

Where’s the scripture? For a mini-series about the Bible that makes a point of showing how conscious its characters could be of the scriptures and traditions that already existed in their day, it is striking — if not puzzling — that the scene of Jesus’ temptation in the desert downplays any reference to the scriptures.

The gospels make a point of showing how Jesus refused each of Satan’s temptations by quoting scripture, and when I was growing up, this story was always held up as an example of how we needed to know our Bibles. But in this episode, Jesus seems to appeal to nothing more than his own impulses.

He does quote the verse about man not living on bread alone but on every word that comes from the mouth of God — but he never says “It is written.” He never makes it clear that he is quoting the words of God himself even as he speaks.

Odds and ends. I’ve already touched on a few of the ways in which this episode oversimplifies things (by removing John the Baptist’s doubts in prison, etc.). One other example of this is the way Mary just accepts Gabriel’s announcement that she will bear a son without objecting, as she does in the Bible, that she is a virgin.

Odds and ends. I’ve already touched on a few of the ways in which this episode oversimplifies things (by removing John the Baptist’s doubts in prison, etc.). One other example of this is the way Mary just accepts Gabriel’s announcement that she will bear a son without objecting, as she does in the Bible, that she is a virgin.

It is also striking how Joseph’s “dream” occurs during the daytime, as he stands in the middle of the street. Note, too, that Joseph receives his dream from Gabriel, thus bringing together the nativity accounts of Matthew (which includes dreams and is told from Joseph’s point of view) and Luke (which includes angels and is told from Mary’s point of view).

Another oversimplification: Pontius Pilate and Herod Antipas are made to look a little chummy, for lack of a better word, which they definitely weren’t at this point in the story. Also, why does Antipas welcome Pilate “to Judea”? Antipas was tetrach of Galilee, and had no jurisdiction in Judea (though his father had been king there a few decades earlier).

Another oversimplification: Pontius Pilate and Herod Antipas are made to look a little chummy, for lack of a better word, which they definitely weren’t at this point in the story. Also, why does Antipas welcome Pilate “to Judea”? Antipas was tetrach of Galilee, and had no jurisdiction in Judea (though his father had been king there a few decades earlier).

Whew. That’s enough for now. Episode four — which will continue but, apparently, not conclude the Jesus portion of this mini-series — airs on Sunday.