In all the years that I’ve been writing about film, I have read only a few screenplays before seeing the films in question. Last week I added Darren Aronofsky’s Noah to that very short list.

In all the years that I’ve been writing about film, I have read only a few screenplays before seeing the films in question. Last week I added Darren Aronofsky’s Noah to that very short list.

The script I read is credited to Aronofsky and Ari Handel and seems to be identical to the one that has already been reviewed by Christian screenwriter Brian Godawa and Hitfix columnist Drew McWeeny. However, I don’t want to say too much about it here, because it seems we’ve all read an earlier draft than the one that was used to make the actual film.

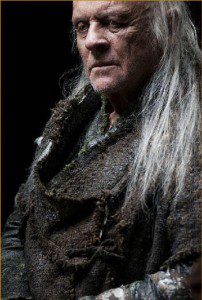

For one thing, when Paramount announced two years ago that it was going to produce the film, they also announced that John Logan had been hired to rewrite the script — yet his name appears nowhere on the undated screenplay that I read. For another, there have been reports for almost a year now that Ray Winstone will be playing a “nemesis” of Noah’s named Tubal-Cain — and yet there is no character by that name in the screenplay that I read.

Now, Noah does have a nemesis in the screenplay that I read, but he goes by the name Akkad — which happens to be the name of one of the cities built by the biblical Nimrod in the years immediately after the Flood. In secular history, this city also lent its name to the Akkadian Empire, a Mesopotamian kingdom that, according to Wikipedia, “is sometimes regarded as the first empire in history”.

So it’s possible that Logan has simply changed the name of Noah’s “nemesis” from Akkad to Tubal-Cain. But I hope he has done a bit more than that, since the Bible says Tubal-Cain had a sister named Naamah and, according to some Jewish traditions at least, this sister was identical to the Naamah (or Naameh) who was Noah’s wife. I’m hoping, in other words, that we’ll see some interesting family dynamics between two mutually antagonistic brothers-in-law and the sister or wife who is caught in the middle — dynamics that are completely absent from the script that I read.

Like I say, I don’t want to say too much about the screenplay that I read, because a lot might have changed between this draft and the one written by Logan, and of course the filmmakers might make all sorts of other changes on the set or in the editing room. But I agree with McWeeny that there is the potential for some truly fantastic imagery here, and I am intrigued by the fact that Aronofsky ties the story of Noah to the creation and fall of mankind more strongly than I had anticipated; I am also intrigued by the way Aronofsky fuses the creation myths of the Old Testament with modern scientific theories about the origins of both our world and our species.

I do, however, want to respond to a few of Godawa’s critiques. In addition to his work as a screenwriter and a film critic, Godawa is also working on a series of novels set partly during this period, the first of which is called Noah Primeval — so he has some truly insightful things to say about the shift in perspective between the original Hebrew texts and the script that Aronofsky has based on them. But there are a few points where I disagree with Godawa’s take on the screenplay itself.

First, noting that the film depicts the Flood partly as God’s response to our devastation of the environment, Godawa writes:

First, noting that the film depicts the Flood partly as God’s response to our devastation of the environment, Godawa writes:

The notion of human evil is more of an afterthought or symptom of the bigger environmental concern of the great tree hugger in the sky.

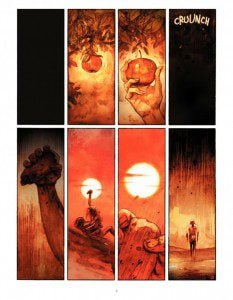

I wouldn’t say human evil is presented here as an afterthought, exactly. The film will apparently begin the same way the graphic novel begins, with Eve’s eating of the forbidden fruit leading directly to the murder of Abel by Cain; this is then followed by a series of screams and noises that play over a black screen, indicating violence of one sort or another. The ruined environment — which is, admittedly, the main concern of the film from that point on — comes after all that violence, and is arguably a symptom of it, not vice versa.

What’s more, the Fall and the bit about Cain and Abel is repeated later on, when Noah tells the Creation story to his family aboard the Ark (a framing device that has already been used in such productions as Testament: The Bible in Animation and this year’s The Bible). And, beyond even that, Noah’s decision to let humanity die out — because he believes the Earth would be better off without us — is motivated by an incident in which he strikes one of his sons out of anger. Pondering his actions, Noah says:

I thought somehow we were different. I look out at all those lost souls and I sympathize with them. They are no different than us. We are no different than them. The same wickedness in all of us. . . . It is not what [the boys] did. It was my response. My anger!

Note: Noah, who has already well established his environmentalist bona fides by this point in the film, thought he was different from the other human beings because he was not prone to violence like them. But it is when he lashes out in anger that he decides even he is too fallen to perpetuate the human race — and if he is too fallen to keep humanity going, then surely any descendants of his would be, too.

So it is mankind’s propensity for violence, and not our tendency to destroy the environment, that pushes Noah over the edge, as it were, there.

Second, Godawa writes:

The primary sin of the script Noah is man’s violence against the environment. Which is kind of contradictory, don’t you think? Claiming that God destroys the entire environment because man was — well, destroying the environment?

This is indeed an old objection to the efforts by some people to turn the story of Noah into an environmentalist fable. And yet it seems pretty clear to me that, in Aronofsky’s film, there isn’t much environment left for God to destroy by the time the story gets started. Indeed, as Godawa himself notes, the only reason movie-Noah has enough wood to build his Ark is because of a magical sort of forest that sprouts up thanks to a magic seed provided by Methuselah. (Although that itself, arguably, raises other questions, like why Methuselah doesn’t help even more plants to grow, to offset the environmental destruction committed by others. But leave that be for now.)

The problem is that Noah is depicted as attempting to follow God’s will in the script, a will that includes the complete annihilation of the human race, as opposed to the Genesis depiction of starting over with eight humans to repopulate and ultimately provide a Messiah.

The script does, indeed, deviate from the Bible in its depiction of God’s plan and the degree to which God spells that plan out for Noah. (There are only six humans in movie-Noah’s family, not eight, for one thing, because only one of his sons is old enough to be married.) But does the God of this film really want to annihilate the entire human race? The script is not as clear on this point as Godawa suggests. At best, it’s actually somewhat ambivalent.

Godawa barely even mentions one of the most pivotal scenes in the entire script, when Naameh visits Methuselah to discuss Noah’s plan to let humanity die out. Godawa does quote the bit where Methuselah says it would be “justice” if humanity was destroyed, but he leaves out the key bit of dialogue that follows that line:

The Creator reaches down to us with two hands. In his left — a sword that shears away wickedness. That is justice. But in his right — a canopy. It shelters us from judgement and creates a space for grace. That is mercy. Which the Creator intends for us now — that is a mystery.

Then, when Naameh asks Methuselah why Noah won’t strive for mercy, Methusaleh replies, “The visions came to Noah. The choice is his.” The implication, as far as I can tell, is that the people to whom God speaks have some leeway to interpret God’s will and to then apply their interpretations. But if Noah is obsessed with “justice”, Methuselah himself acts in a way that opens the door for “mercy”, and it is not at all clear that God endorses Noah’s plan more than he endorses Methuselah’s.

Godawa argues that Noah seems to have God on his side because the animals on the Ark rally to Noah’s side when he sets out on one particularly drastic course of action (a sequence that one person has compared to The Beastmaster, a 1982 film about a man who can communicate telepathically with animals). But Methuselah’s intervention, itself, has a strong element of the supernatural — and given that Methuselah is the wise one that everyone turns to for help, I think it is at least possible that the film expects us to get our clearest view of God’s will, such as it is, through him.

Godawa, however, makes no reference to Methuselah’s supernatural intervention. So, while Godawa does make some valid points about the film and its deviations from both scripture and Jewish tradition, there’s a big hole there in his critique of the film and the themes it develops. Or so I would argue, at any rate.

But again, I don’t want to spend too much time going back and forth over the details in this script, since we currently have no idea how closely it will resemble the actual film that comes out in March of next year. For now, though, I do think it’s worth noting that it looks like Aronofsky’s film will be more ambiguous or ambivalent than some of its critics are currently giving it credit for.

(P.S.: For what it’s worth, I also think the film will be more ambiguous or ambivalent than some of its supporters give it credit for! Conservative Christian lobbyists like Movieguide founder “Dr.” Ted Baehr have already claimed that the film will be “incredibly redemptive” and “God-centered”, which strikes me as an oversimplification in the exact opposite direction. Expect there to be a lot of ballyhoo about the film’s biblical “accuracy” when it comes out, too.)