Darren Aronofsky recently said he wants his upcoming movie Noah to “smash expectations of who Noah is”.

Darren Aronofsky recently said he wants his upcoming movie Noah to “smash expectations of who Noah is”.

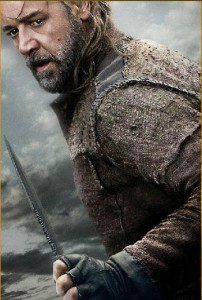

And Russell Crowe said last year that the title character, played by him, is “not benevolent. He’s not even nice.”

The Gospel Herald has now picked up on these quotes and combined them with Monday’s bogus Variety story to suggest that the film will contradict the Bible, which describes Noah as a “righteous man”.

But what does that phrase even mean?

Let’s start with Aronofsky’s quote.

In context, it’s clear that he was talking not necessarily about Christian perceptions of Noah, but about the general perception of Noah that everyone has grown up with — everyone, that is, who has ever stepped inside a preschool or nursery where the walls are decorated with images of a man and a boat and lots of smiling animals.

As Aronofsky said in the sentence that immediately followed his “smash expectations” quote: “The first thing I told Russell is, ‘I will never shoot you on a houseboat with two giraffes behind you.'”

So basically he’s “smashing” a pop-cultural image of Noah as much as he is doing anything else. He’s asking people to stop treating the story as a children’s fable and to take it more seriously. And surely, even conservative Christians have done that sort of “smashing” from time to time.

Conservative Christians might not have the resources to make $125 million movies, but surely we have told sermons and published books that challenged popular misconceptions about the Bible and its characters, including misconceptions that were popular among our fellow conservative Christians. (Philip Yancey’s book The Jesus I Never Knew — in which Yancey used films about Jesus to help him rethink some of his ideas about our Saviour — comes to mind.)

Beyond that, Aronofsky is also drawing our attention to the fact that Noah basically witnessed the destruction of his world. Not just a city or two, like Sodom and Gomorrah, but the entire civilization within which he had been raised.

As Aronofsky recently told Total Film, “it’s truly the first apocalypse story.”

So Aronofsky is trying to get us to think about that, too.

And because he is taking the story as seriously as he is, and populating it with characters who have some semblance of realistic psychology, he is also trying to get us to think about the effect of this apocalypse on the small group of people who survived it.

As Crowe has put it, Noah is the guy who stood and watched as everyone died. And as Aronofsky put it when he first expressed interest in making this film seven years ago, Noah had “some real survivor’s guilt” — an interpretation that Aronofsky bases partly on the fact that the Bible itself tells us Noah built a vineyard shortly after he survived the Flood and got so drunk on his own wine that he passed out naked.

It’s possible the drunkenness was a one-time thing. It’s possible that it wasn’t part of an ongoing habit. But Aronofsky’s interpretation is certainly a legitimate one.

And certainly, in my own experience growing up evangelical, the fact that Noah got drunk was often cited as one of the ways in which the Bible kept reminding us that even its heroes were fallen. (As Steve Taylor said when I interviewed him in 1994, “one of the great things about the Bible is it just gives it to you straight, y’know? You get both sides of the story with Gideon and Noah and whoever.”)

So the fact that Aronofsky has taken Noah’s drunkenness into account should not be considered a stroke against the film. Quite the opposite, in fact.

Now it is true, as The Gospel Herald notes, that the New Testament speaks of Noah’s righteousness. There is Hebrews 11:

By faith Noah, when warned about things not yet seen, in holy fear built an ark to save his family. By his faith he condemned the world and became heir of the righteousness that is in keeping with faith.

And there is II Peter 2, which calls Noah “a preacher of righteousness”.

Noah was righteous in the sense that he “walked faithfully with God” at a time when most other people were “wicked”. And he was righteous in the sense that, when God told him to build the ark and thereby save both the human race and the various animal species from complete destruction, he went ahead and did that.

But calling someone “righteous” does not mean that they are perfect, nor does it mean that they can’t have a dark side.

Consider that passage in II Peter, which puts Noah and Lot in the same category.

Lot is the guy who tried to protect his visitors from gang rape by letting the mob sexually assault his daughters instead. And then, after witnessing both the destruction of his home and the death of his wife, Lot ended up getting drunk in a cave somewhere and impregnating both of his daughters.

Was Lot a righteous man? Compared to his neighbours in Sodom, sure… I guess. But let’s not overpraise him. Let’s not forget the other parts of the story that make him a much more complicated character.

And as for that passage in Hebrews: What would it look like if a man was filled with “holy fear” and “condemned the world” around him? Might his fear get the better of him? Might he go too far with his condemnation of that world? Might his zeal for God’s justice overwhelm his openness to God’s mercy?

The tension between God’s justice and God’s mercy is something we believers all have to deal with. And it sounds like this film will wrestle with that too.

Unfortunately, we believers have a tendency to downplay the sides of our heroes that can make us a bit uncomfortable. And you can arguably see this process happening within the Bible itself — starting with those New Testament passages that focus on the righteousness of Noah or Lot (or Samson, etc.) without acknowledging the parts of their stories that are more, um, disreputable.

And certainly, throughout church history, there has been a tendency to make the saints look better than they probably were. You see this not only in the hagiographies that have been written over the years, but also in films that reduce figures like Elijah to bastions of holiness who show none of the human qualities — the doubts, the fears, the hesitations — that the Bible ascribes to them.

But no one pays ten bucks a ticket to sit through propaganda of that sort. People go to the movies to see stories that they can relate to on some level. Even the recent wave of comic-book movies — movies that draw fairly clear-cut lines between good guys and bad guys — have made a point of showing how their superhero protagonists sometimes wrestle with their faults.

So by all means, let Aronofsky explore the darker, more complicated side of the Noah story. Let him take the audience on Noah’s journey as Noah hears his message from God (which is real, after all; the Flood does happen), and as Noah tries to figure out how to apply that message to his life beyond simply building the Ark.

Maybe Aronofsky will do a really good of balancing all the issues at play. Maybe he won’t.

But if even half of what we’ve heard about this film is true, I do hope that it will encourage us to think about the cost involved — socially, psychologically, domestically — when God calls on us to do something and we heed his call.

And I hope it will get us to think about the ways in which our obedience to God hinges on our understanding of God, which may or may not be accurate.

To put this another way, I don’t want Aronofsky’s film to give us all the answers. I want it to stimulate good questions. And I hope the people who see it, or who are thinking of seeing it, will be willing to entertain those questions.