Church of the Holy Trinity v. U.S.

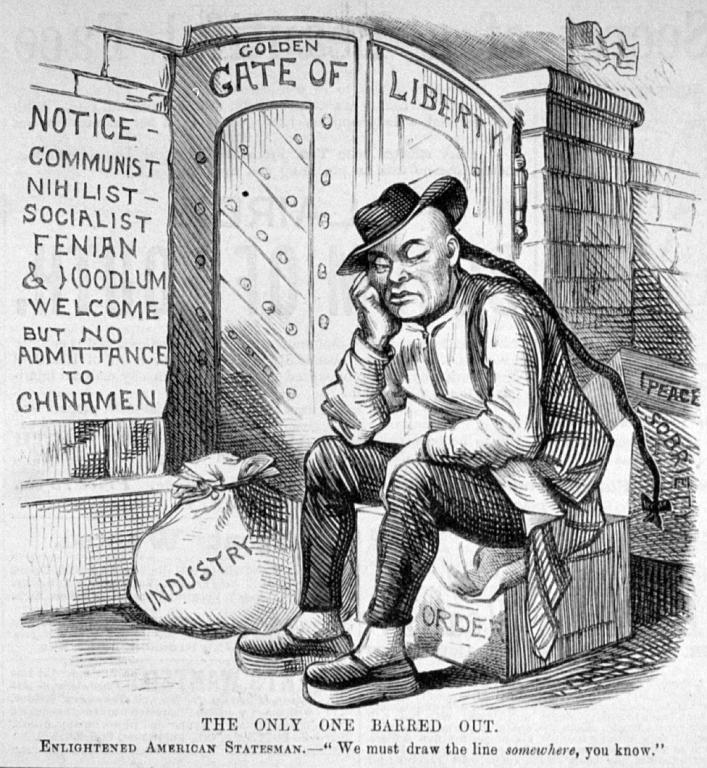

“There is no dissonance in these [legal] declarations. …These are not individual sayings, declarations of private persons: they are organic [legal, governmental] utterances; they speak the voice of the entire people. …These, and many other matters which might be noticed, add a volume of unofficial declarations to the mass of organic utterances that this is a Christian nation.” – Church of the Holy Trinity v. U.S., 143 U.S. 457 (1892). Unanimous Decision Declaring America a Christian Nation Significantly, the U. S. Supreme Court cited dozens of court rulings and legal documents as precedents to arrive at this ruling; but in 1962, when the Supreme Court struck down voluntary prayer in schools, it did so without using any such precedent.

VERDICT: Deliberately Misleading

The real issue with this quote is Hobby Lobby’s description of the case, which is inaccurate. This case involved the Alien Contract Labor Law of 1885. The court did not declare (i.e., it did not hold, but only stated in dicta) that this is a Christian nation. The court ruled that the Alien Contract Labor Law did not prevent churches from contracting to bring pastors from other countries to minister to their congregation. That’s it. It was an issue of statutory interpretation. The opinion, written by Justice David Brewer, makes the statement, but it is not really relevant to the case or holding.

Coming from Brewer, a devoutly religious “[s]on of a Congregationalist minister-missionary” and former Sunday school teacher, the claim should not be surprising. Steven K. Green, Justice David Josiah Brewer and the “Christian Nation” Maxim, 63 Alb. L. R. 427, 433 (1999). Of course, if Hobby Lobby wanted to truly relate Justice Brewer’s meaning in these two paragraphs, they should have looked to the book he wrote to clarify them, The United States A Christian Nation. Brewer, referring to his Holy Trinity opinion, asks and answers a question Hobby Lobby’s dearth of subtlety prevents them from comprehending:

But in what sense can it [the United States] be called a Christian nation? Not in the sense that Christianity is the established religion or that the people are in any manner compelled to support it. On the contrary, the Constitution specifically provides that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Neither is it Christian in the sense that all its citizens are either in fact or name Christians. On the contrary, all religions have free scope within our borders. Numbers of our people profess other religions, and many reject all. Nor is it Christian in the sense that a profession of Christianity is a condition of holding office or otherwise engaging in the public service, or essential to recognition either politically or socially. In fact the government as a legal organization is independent of all religions.

So we are not a Christian nation in any meaningful way. Brewer falls short. He relies mostly on our pre-constitutional, colonial history – that religious people came to this country originally, some on religious missions. When it comes to actually showing that our government and laws are substantively based on Christianity, Brewer demurs:

I could show how largely our laws and customs are based upon the laws of Moses and the teachings of Christ; how constantly the Bible is appealed to as the guide of life and the authority in questions of morals; how the Christian doctrines are accepted as the great comfort in times of sorrow and affliction, and fill with the light of hope the services for the dead. . . . But I must not weary you.

Brewer claims he “could show,” but if he could have, he would have. Many have tried to show that our Constitution and laws are Christian or biblical, but it simply cannot be done.

Hobby Lobby’s description of Supreme Court precedent that “struck down voluntary prayer in schools” is misleading. Hobby Lobby doesn’t provide a case citation, only a year: 1962. It appears to be referring to Engel v. Vitale, a 1962 case. Hobby Lobby’s description of the case is inaccurate, and the factual description is more similar to Abingdon v. Schempp, a 1963 case, than Engel. Either way, the Supreme Court has never “struck down voluntary prayer” in school. Schempp prohibited schools from “requiring the selection and reading at the opening of the school day of verses from the Holy Bible and the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer by the students in unison.” Sch. Dist. of Abington Twp., Pa. v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203, 223 (1963) (emphasis added). These were not voluntary, they were “required” and “prescribed as part of the curricular activities of students who are required by law to attend school.” Id.

If Hobby Lobby was referring to Engel v. Vitale, the description is misleading. There, a school board actually wrote a prayer for students to recite every day. The “prayer was composed by governmental officials as a part of a governmental program to further religious beliefs.” Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421, 425 (1962). This clearly violates the Constitution: “the constitutional prohibition against laws respecting an establishment of religion must at least mean that in this country it is no part of the business of government to compose official prayers for any group of the American people to recite as a part of a religious program carried on by government.” Id. Read the case; the prayer was not voluntary. A government-imposed duty, or even request, to pray is naturally coercive: “When the power, prestige and financial support of government is placed behind a particular religious belief, the indirect coercive pressure upon religious minorities to conform to the prevailing officially approved religion is plain.” Id. at 431. Even the dissent recognized that students’ Free Exercise rights, i.e., their ability to engage in voluntary prayer, were not an issue in the case: “The Court does not hold, nor could it, that New York has interfered with the free exercise of anybody’s religion. For the state courts have made clear that those who object to reciting the prayer must be entirely free of any compulsion to do so, including any ‘embarrassments and pressures.’” Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421, 445 (1962) (Stewart, J., dissenting) (citations omitted).

Contrary to Hobby Lobby’s post-quote assertion, the Court used precedent. The majority relied primarily on “our Constitution, and our Bill of Rights with its prohibition against any governmental establishment of religion.” Id. at 433. But it also cited copious history, texts, and James Madison’s Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments. What Hobby Lobby means to say is that no other Supreme Court precedent was cited (even though, technically, the majority did cite Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1 (1947) in a footnote and Justice Douglas’ concurrence cited: McCollum, etc. v. Board of Education, 333 U.S. 203 (1948); Zorach v. Clauson, 343 U.S. 306 (1952); McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420, 563 (1961)). Notice the bait and switch: Hobby Lobby’s precedent standard for Church of the Holy Trinity was “court rulings and legal documents as precedent,” but for the unnamed 1960s decision legal documents such as the Constitution and Bill of Rights did not count as precedent, only court decisions would do.

In Schempp, the 1963 case, the Supreme Court explained this further: “in Engel v. Vitale, only last year, these principles were so universally recognized that the Court, without the citation of a single case and over the sole dissent of Mr. Justice STEWART, reaffirmed them.” Sch. Dist. of Abington Twp., Pa. v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203, 220-21 (1963). In the Schempp decision, from pages 214 through page 222 the Court is only citing, discussing, and examining precedent. The Court cited: Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421 (1962); Zorach v. Clauson, 343 U.S. 306 (1952); Bureau of the Census, U.S. Department of Commerce, Statistical Abstract of the United States (83d ed. 1962); James Madison, Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments; Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1 (1947); Board of Education of Cincinnati v. Minor, 23 Ohio St. 211 (1872); Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296 (1940); Murdock v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 319 U.S. 105 (1943); McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420 (1961); Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488 (1961); People of State of Ill. ex rel. McCollum v. Bd. of Ed. of Sch. Dist. No. 71, Champaign Cnty., Ill., 333 U.S. 203 (1948); West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943); The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment; The Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment; and The Fourteenth Amendment.

Justice Brennan’s concurrence cites even more precedents, including plenty showing the importance of secular education long before the 1960s:

- “. . . President Grant’s insistence that matters of religion should be left ‘to the family altar, the church, and the private school, supported entirely by private contributions.’” Schempp, 374 U.S. at 273 (Brennan, J., concurring).

- “. . . Theodore Roosevelt’s declaration that in the interest of ‘absolutely nonsectarian public schools’ it was ‘not our business to have the Protestant Bible or the Catholic Vulgate or the Talmud read in those schools.’” Id.

- “. . . the message of an Ohio Governor who vetoed a compulsory Bible reading bill in 1925: ‘It is my belief that religious teaching in our homes, Sunday schools, churches, by the good mothers, fathers, and ministers of Ohio is far preferable to compulsory teaching of religion by the state. The spirit of our federal and state constitutions from the beginning (has) been to leave religious instruction to the discretion of parents.’” Id. at 273-4.

- “. . . the opinions of the Attorneys General of several States holding religious exercises or instruction to be in violation of the state or federal constitutional command of separation of church and state.” Id. at 274.

- “. . . the courts of a half dozen States found compulsory religious exercises in the public schools in violation of their respective state constitutions” including Illinois, Louisiana, Wisconsin, South Dakota, Washington, and Nebraska. Id.

In conclusion, whichever case Hobby Lobby is referring to, a student’s ability to voluntarily pray in their own way in school has never been in danger.

Source: Holy Trinity Church v. United States, 143 U.S. 457 (1892). The Holy Trinity decision. Brewer’s book, The United States A Christian Nation.