That evangelicals and other conservative Christians tend to be such big supporters of the non-evangelical, non-conservative- Christian Donald Trump has occasioned much criticism and soul-searching. But new research adds an intriguing (though still debatable) twist: Trump’s biggest supporters in the Republican primary were indeed evangelicals whose religion is very important to them but who don’t go to church.

From Timothy P. Carney, Why ex-churchgoers flocked to Trump, Philanthropy Daily:

The best way to describe Trump’s support in the Republican primaries—when he was running against the likes of Jeb Bush, Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, John Kasich—would be: white evangelicals who do not go to church.

Geoffrey Layman, a political science professor at the University of Notre Dame, noticed this during the primaries, writing: “Trump does best among evangelicals with one key trait: They don’t really go to church.”

While writing my forthcoming book, Alienated America, my research assistant Nick Saffran and I crunched some numbers provided by Emily Ekins of the Voter Study Group. We broke down Republican primary voters by church attendance. Among the most frequent attenders—those going more than once a week—Trump got about 32 percent of the vote.

Trump also got a minority of those who simply go once a week. Among those who reported going “a few times a year,” Trump got about half. He got an easy majority (55 percent) of those Republicans who “seldom” attend, and a full 62 percent of those who never attend. That is, every step down in church attendance brought a step up in Trump support, and vice versa. The most frequent attenders were half as likely to support Trump as were the least frequent attenders.

This confirmed what others had noticed. Liberal Peter Beinart wrote for The Atlantic that the GOP electorate has secularized, and that this secularization “helped Trump win the GOP nomination.”

In March, as the GOP field was narrowing down to Trump and Cruz, one Pew Research Center survey found Trump trailing by 16 points among white evangelical voters who attended church weekly, but leading by 19 points among those who do not.

The author, Mr. Carney, stresses that these non-church-going evangelicals are not to be dismissed as nominal Christians. They have strong religious beliefs and say that their faith is very important to them. But they do not go to church. And this is a large number of American Christians. The author goes on to speculate about why this is, that Trump somehow fills a void once occupied by church.

First of all, this is a study of the Republican primary. There were many conservative candidates to choose from. Once Trump got the nomination, most evangelicals did vote for him and continue to support him. And why shouldn’t they, if they are, for example, single issue voters for the pro-life cause? Or anti-socialist? Or worried about religious liberty? Or any number of other issues, in which Trump supports their position and the Democrats most emphatically do not?

But these findings point to some larger factors that we have been harping on at this blog.

Most of this data can be accounted for in terms of Trump’s support among the low-income white working class. This is pretty much the demographic that is the most unchurched. And they have lots of reasons to support Trump.

Though they don’t go to church, these folks generally consider themselves to have strong Christian beliefs. Which brings up a phenomenon that is bigger than politics: Churchless Christianity.

Despite the dramatic drop-off in church attendance and affiliation, most people who are doing without church still retain religious and often Christian beliefs. This is true even of the “Nones.” It is true even in sophisticated Europe.

This represents a major challenge for orthodox Christianity, since the church is of supreme importance. Churchless Christianity is a different kind of Christianity altogether. This topic deserves its own post, so stay tuned for that.

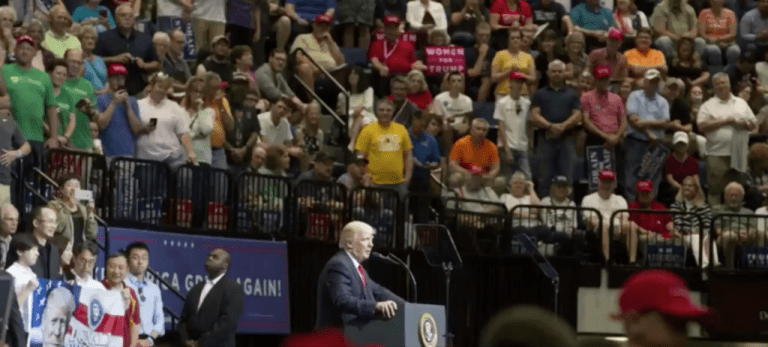

Photo: Trump rally in Cedar Rapids, Iowa [one of the least churched cities in the nation ], Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons