As Christians are trying to figure out how they should pursue politics and cultural influence in our secularist world, it is helpful to consider models from the past.

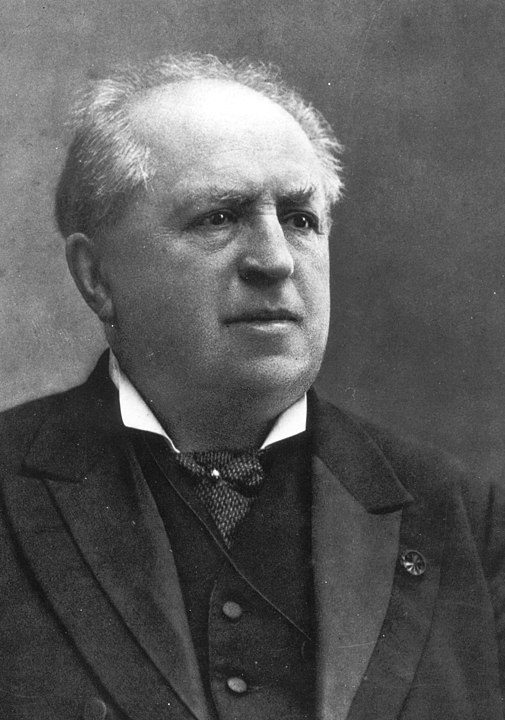

Jordan Ballor does that in his Religion & Liberty article The Faithful Christian and the Politics of the Tao. In it, he looks at the political activities of the Reformed theologian Abraham Kuyper (1837–1920), who not only started a successful Christian political movement in the Netherlands but actually rose to the position of Prime Minister.

In 1879, he founded the Anti-Revolutionary Party. An odd name for a political party, perhaps, describing what it was against rather than what it was for, but its focus was to oppose the legacy of the French Revolution, which continued to manifest itself in ever-more radical but mostly unsuccessful revolutions in Europe throughout the 19th century, from the widespread liberal revolutions of 1848 to socialist riots that in the next century would culminate in the Russian Revolution.

I was somewhat familiar with Kuyper, mainly from back when I was influenced by Francis Schaeffer, especially with his emphasis on “world views.” His political efforts I chalked up to the Calvinist “one-kingdom theology” that stresses the rule of the saints on earth, with the theocratic goal of ruling earthly societies with God’s law, which even Christians–let alone non-believers–are unable to keep.

But Ballor’s article showed me that I had misjudged Kuyper’s project. He didn’t start a “Christian Party,” much less a “Calvinist Party” designed to set up a millennial Christian utopia. Rather, his “Anti-Revolutionary Party” was oriented around a negative goal of opposing the anti-clericalism, the attacks on the family, and the undermining of other institutions that the spirit of revolution encouraged. At the same time, the “Anti-Revolutionaries” sought to offer more positive alternatives to the genuine problems–the exploitation of labor, poverty, inequality, etc.–that the revolutionaries were trying to address.

You couldn’t say that the “Anti-Revolutionary” party was conservative, at least in the old European sense of trying to build up the power of the monarchies, restoring the aristocracy, and imposing controls on the lower classes. Rather, Kuyper presided over what was, in effect, a populist movement. Says Ballor,

A distinctive feature of Kuyper’s emphasis was on the importance and dignity of the kleine luyden, the “little people.” In this way the ARP was fiercely and deeply democratic, grounding its principles in the dignity of all human beings, each with a vocation before God and a service to provide for others. “Everything can be a spiritual calling,” wrote Kuyper, and everyone should be respected and represented in the political order. This meant a focus on expanding the franchise more broadly (although not universally in a revolutionary fashion), even as it also meant focusing on the family as the basic unit of society.

Central to Kuyper’s political and theological convictions was the concept of “sphere sovereignty,” the notion, in Ballor’s words, that “God has given direct authorization to various social institutions, or ‘spheres,’ which operate according to their own logic and laws and ultimately are accountable to God.” The state has its sphere of sovereignty, but so does each family. Also the church, local governments, schools, businesses, workshops, and many more.

It follows that Kuyper believed in limited government and the decentralization of authority. So what is the role of government in all of these spheres? Ballor explains (my bolds):

While authority and legitimacy were not delegated by the state or through the government to the various spheres, the state did have a unique responsibility to be the forum of last resort for public justice. When conflict arises between the spheres, or there is corruption within an institution such that it needs aid to restore its proper functioning, the state can act in a remedial capacity. The purpose of state intervention, however, is always to restore spheres and institutions to health and self-sufficiency.

The purpose of the state is to protect and build up the other spheres–the family, the schools, economic institutions, local governments, private organizations, and, yes, the church–which strikes me as a principle that Christians interested in politics could apply today. This is a Christian model that is not Catholic “integralism,” with its dreams of papal and imperial rule, nor is it a “post-liberal” model that downplays democracy and individual rights. Rather, it is a Christian kind of liberalism as an alternative to the revolutionary kinds of liberalism.

Kuyper saw that his concept of sphere sovereignty was similar to the Catholic teaching about “subsidiarity,” defined as “the principle that a central authority should have a subsidiary function, performing only those tasks which cannot be performed at a more local level.” In 1891, Pope Leo issued the encyclical Rerum Novarum, which applied that principle in many ways, including affirming the dignity and rights of workers while rejecting socialism. The arch-Calvinist Kuyper loved that proclamation from the Pope, to the point that his Anti-Revolutionary Party allied with its Catholic counterparts. According to the politics of this unlikely alliance, the Calvinists and the Catholics would vote for each other’s candidates on second and subsequent ballots in jurisdictions where their party would fall short. This tactic, which would work better in a multi-party parliamentary system rather than a two-party system like ours, led to a coalition that would enact many of the ARP’s policies and make Kuyper Prime minister.

And yet, Kuyper was voted out of office in 1905, and his political program did not survive the two World Wars. The Anti-Revolutionary Party did persist until it merged with other Christian-related parties in 1974 to become part of the Christian Democratic movement, which is another but related approach to Christianity and politics. (See my posts from years ago: Conservative Theologically, but Liberal Politically and Kuyper and Christian Democracy; and my posts on the American Christian Democratic party that may be on your ballot, the Solidarity Party. Check out the party’s website to learn about its presidential candidates, Peter Sonski and Lauren Onak, the thoroughly pro-life alternatives.)

My impression is that “sphere sovereignty” and “subsidiarity” accord well with the Lutheran doctrine of the Estates and the doctrine of vocation. And yet the Anti-Revolutionary Party’s ultimate demise is also confirmation of the Lutheran pessimism about the ability of sinful human beings to establish a consistently moral and Godly society on earth. Christianity is not a political program but the good news of our salvation through Christ. Still, though, God reigns in a hidden way in His temporal kingdom, so we must never reject that temporal kingdom, but rather do what we can in our various vocations, including that of citizenship, to love and serve each other.

So what can we learn from Kuyper?

Photo: Abraham Kuyper by Unknown author – https://josdouma.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/kuyper-75.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=43933631