“Being a free American requires practically loving your neighbors so that the government doesn’t have to love them for you.”

That’s the conclusion of a fascinating essay by Cameron Hilditch entitled America’s Unwritten, Unraveling Constitution. You might recognize in that line the doctrine of vocation, which, as we keep saying, is not so much about our self-fulfillment as about loving and serving our neighbors.

Thus, Hilditch is suggesting that vocation is at the heart of America’s unwritten constitution.

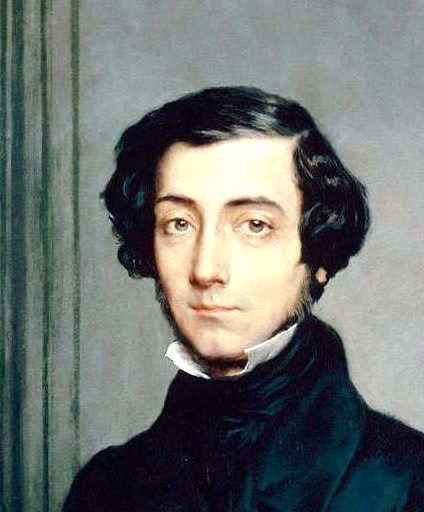

He is discussing Alexis de Tocqueville’s analysis of American culture in his 1835 classic Democracy in America. Hilditch points out that de Tocqueville, in trying to work out why American democracy avoided the dysfunctions of the French revolution, says little about the written framework set up in the U.S. Constitution. Rather, he is trying to understand the “constitution” of the United States in an earlier sense; namely, how this nation is “constituted,” how it is made up and how it functions, according to its folkways and culture.

De Tocqueville is trying to understand how it is possible for a nation to be both democratic and decentralized. “It was the social practices of Americans, their actions rather than their ideas, that constituted the true greatness of the country in his eyes.” This is the “unwritten Constitution” that, in turn, formed the written, legal document.

De Tocqueville cited the importance of America’s local governments and associations, from churches to town meetings. Life on the frontier gave Americans the habit–born of necessity–of banding together.

In the colonial and revolutionary eras, for instance, the material difficulties of life in a new land required that Americans depend on the work of their neighbors for their survival. This necessity of associating with one another to organize, compromise, and solve local problems recreated in democratic America the dense local and regional allegiance and autonomy that had existed in feudal France. The experience of convening with neighbors to solve problems also made the prospect of a distant and faceless central government both unappealing and unnecessary. As a result, Americans’ habit of joining local organizations did more, in Tocqueville’s eyes at least, to limit the reach of the federal government than any abstract philosophical or political principle. It made the American republic free in fact, not just in theory.

I want to imagine under what new traits despotism will appear in the world. I see an innumerable multitude of similar and equal people will turn incessantly in search of petty and vulgar pleasures, with which they will fill their soul. Each, standing apart, is like a stranger to the destiny of others; his children and personal friends forming for him the entire human race. As for the remainder of his fellow citizens, he is beside them, but he does not see them. . . .

He exists only in and for himself, and even if he still has a family, one can say that he no longer has a country. Above these people rises an immense and tutelary power, which alone takes charge of assuring their pleasures and looking after their fate. It is absolute, detailed, regular, foresighted, and mild. It would resemble paternal power, if, like it, its object was to prepare men for maturity. But it only seeks, on the contrary, to fix them irrevocably in childhood. . . .

It willingly works for their happiness. It looks after their security, foresees and assures their needs, facilitates their pleasures, regulates their principal affairs, directs their industry. . . .

Why does it not entirely remove the trouble of thinking and the difficulty of living? In that way it makes even less useful and rarer the exercise of free will, enclosing the action of the will in an ever smaller space. . . .

Equality has prepared men for all these things. It disposes them to endure them and often even to regard them as a benefit.

Sound familiar? Are we there yet?

Illustration: Portrait of Alexis de Tocqueville (detail) (1850), by Théodore Chassériau, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons