It looks like marijuana will soon be legalized everywhere. There is no organized opposition–not even among conservative Christians–so I see nothing that will stop it. When that happens, it is likely to pass into general use. Eventually, it may become a normal accompaniment of everyday life. If that happens, how do you think widespread marijuana use will change the culture?

The apologists for the drug think it will be a medical panacea and that it will usher in an era of peace, love, and understanding. The skeptics will make jokes about a stoned nation void of ambition and constantly afflicted with the munchies. But, seriously, what might be its cultural effect? Will people become less angry and more “mellow”? What might marijuana do to our music, art, and entertainment? (OK, maybe those are already created under the influence.) Will a marijuana haze make the general public more introspective or more social? Will people have the drive that built the nation or lapse into passivity?

I have no idea. But I do suspect that cultural marijuana will make people religious. That is, having a particular kind of religion. They will most emphatically not be scientifically-materialistic atheists. But they will not necessarily be religious in a Christian sense, though perhaps Christians can get through to them. The church would do well to prepare for this kind of “spirituality.”

The new strains of marijuana available today, I am told, are much more powerful than anything Baby Boomers experimented with in the 1960’s. I am also told that different products sold in the dispensaries–and we now have one in our little rural town, though requiring an easily procured medical license–are marketed for different effects and different kinds of highs. One of those is a high that is “mystical.” Drugs are often said to “open the mind” to “transcendent experiences.”

I came across a post (HT: George Strieter) from a couple of years ago from E. D. Watson, a writer and artist. I believe she is a Catholic. She describes her life-long yearning for mystical experience and tells how marijuana helped her to find that. I urge you to read it all. Note too why she gave it up. Read it all, but here are some excerpts.

From E. D. Watson, CONFESSIONS OF A MYSTIC MANQUÉ:

As an undergraduate anthropology student, I took a class on worldwide religious rituals, wherein I learned that the whole point of drugs, as far as many non-industrial cultures are concerned, is access to the Divine. The idea of recreational drug use—getting stoned and playing hours of Mario Cart, say—would be blasphemous. . . .

The drug [marijuana] interrupted the steady stream of self-criticism that makes creative endeavors a slog. Moreover, I also found that when high, there was an easy, crystal-clear line of communication between myself and God. Sitting on the floor with paper and glue spread around me like a planetary ring, I could pose theories to God. I could ask questions. Responses arrived inside my mind without delay. The voice that spoke was not the familiar voice that narrates my near-constant internal chatter. It was gentle, vast, and succinct. Though I didn’t always like the answers, their inherent truth was undeniable.

But after a few years, I began to feel like God wanted me to stop.

I resisted at first. Why would God want me to stop doing the thing that allowed us to hang out together and have conversations? It was societal pressure, I decided. I was at the age where a person has to decide who and how they want to be. Did I want to be a status-quo person with clean urine and health insurance, or did I want to talk to God? That question was easy to answer.

I kept getting high, but it wasn’t the same anymore. I could still “hear” the voice I’d come to think of as God’s, but I began to detect a level of disappointment in our conversations. The voice, which was infinitely patient, never scolded me, but I could tell that It—whatever It was—was weary of the routine we’d established. This realization stung. . . .

Not long after that, I gave it up.

The silence stunned me like a hammer-blow. When I’d go outside, the sky was just the sky; the trees mere trees. There were no messages beneath the thin surface of reality. Nothing throbbed with meaning. To say that I missed God would be putting it lightly. The line had gone dead. I could have started smoking again, but I feared a cosmic rebuke. For months I was an excommunicant, roaming wordless wilds. My art and writing dried to a trickle. . . .

. . . True mystical experiences are not a cozy living room to which one might retire at leisure. They are conferred at God’s discretion, if at all. Drugs were, in hindsight, my way of trying to force God’s hand.

This is not inchoate “spirituality.” This is a testimony of a theist. God talks to her. She talks to Him. They chat. She has a personal relationship with God. They “hang out.”

This is a pure example of “enthusiasm,” of religion and of God Himself as sheer experience. It is an attempt to know God wholly apart from His Word.

I won’t say that Watson approaches God with no sense of her sinfulness or that there is more to Him that she perceives. She is a Christian at some level, and other of her writings show that she has a theology. Here she senses God’s disapproval at their drug-enabled communion, feeling that He is disappointed in her. Finally, she realizes that drugs are “my way of trying to force God’s hand,” that God must have the initiative, an intuition that we must be dependent on God’s grace.

People today have trouble even conceiving of God and they tend to be oblivious to spiritual reality. Drugs can help that, I suppose, but at the cost of reducing Him to a mental sensation, a high. And yet some Christians say that they get high on Jesus. But if being high is what they get from Jesus, how is that any different than getting high on drugs?

Christianity is not about feelings, however mystical and transcendent, but about truth. It has to do with language–God’s Word–and His coming in the flesh of Jesus Christ. It’s about the Cross–Christ’s suffering and our suffering; His death and our death; His resurrection and our resurrection–and it is about vocation and loving and serving one’s neighbor. Again, I’m pretty sure that Watson knows this, but a marijuana devotee–or a “Jesus-makes-me-high” devotee–might miss it all, while being quite satisfied by enjoying a constant religious high.

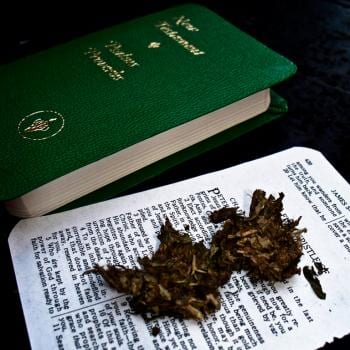

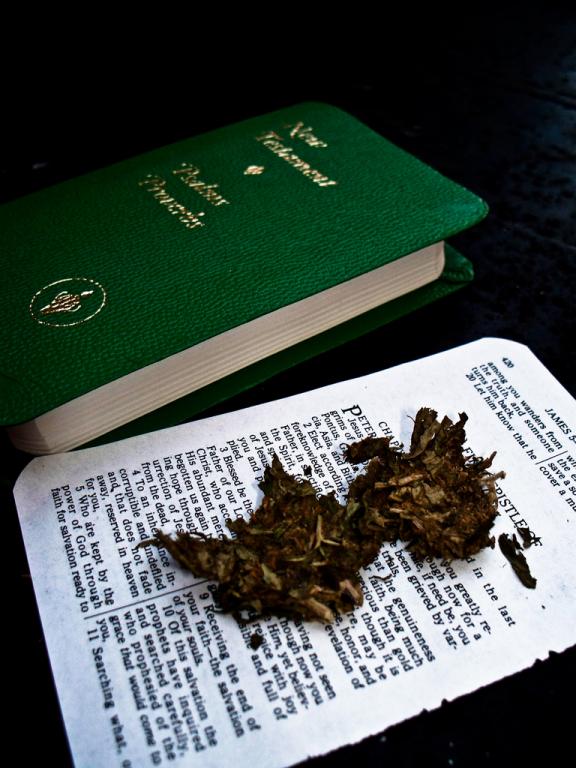

Rastafarians consider marijuana to be a sacrament. The Native American Church uses peyote as a sacrament. (Activists in Colorado, having legalized marijuana, are now working to legalize “magic mushrooms.” Colorado will be so religious.) Watson was using marijuana in that way, as a means of grace, as a way to connect with God. The actual sacraments connect us to God by faith. And they do so through Christ.

How might Christians reach out to someone with a marijuana-infused religion? Pastors, how would you deal with a member of your flock who is full of this kind of “experience” with God? How can we penetrate the haze with the Law and the Gospel?

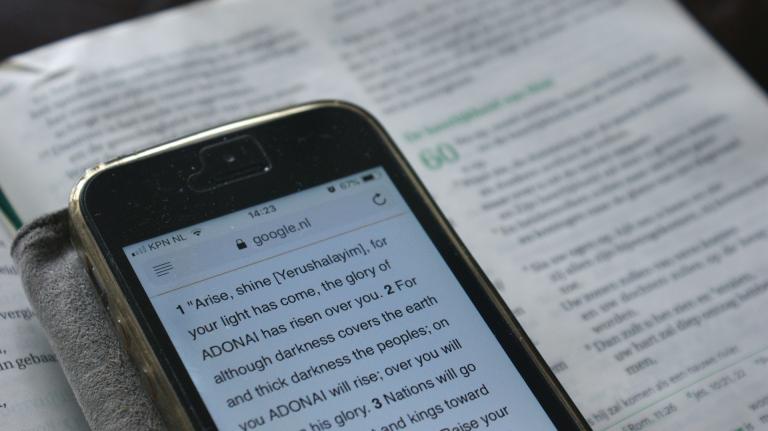

Photo: “Forgive Me Father For I Have Sinned,” by Adrianna Broussard via Flickr, Creative Commons License