Would you use a tradition presentation to preach the gospel to a “Tiger Mom“?

In the last point, I suggested that traditional formulations and methods may not address Eastern questions and problems.

In the last point, I suggested that traditional formulations and methods may not address Eastern questions and problems.

For example, in my first point, I noted that the Tiger mom’s rigorous and self disciplined zeal for perfection is not like that of Luther, who worried how God would accept him as an imperfect sinner. As with other Chinese people, Chua is not thinking about God at all. This leads us to my second point.

(2) We want to ask, “What are the possible motives behind this sort of thinking?”

As I’ve pointed out in previous posts, the quest for perfection may not be a “legalist” problem at all. Rather, it may express a person’s desire for “face,” wanting to be accepted by a group and so avoid the shame and insecurity of isolation.

From a parent’s perspective, people don’t want to see their kids fail, be excluded, and feel ashamed. Not only that, no parent wants to look bad themselves due to the problems stemming from their kid’s lack of discipline. Before being quick to criticize the selfishness of a “tiger mom,” what parent has not worked out of this same sort of thinking? For example, parents compromise and don’t do what is right simply because their kids embarrass them in public. Also, many families even in the West appeal to “family pride” and uphold the family name.

Even Westerners understand this very basic law of human community: we share the honor and shame of those with whom we identify. This fact has untold implications for theology and ministry.

(3) “Easterners” and “Westerners” typically have different assumptions about human nature.

Chua explains her rationale:

Chinese parents demand perfect grades because they believe that their child can get them. If their child doesn’t get them, the Chinese parent assumes it’s because the child didn’t work hard enough. That’s why the solution to substandard performance is always to excoriate, punish, and shame the child. The Chinese parent believes that their child will be strong enough to take the shaming and to improve from it.” (p. 52-53).

Chinese thinking sees human nature as fundamentally good. Western culture, because of the Church’s emphasis on sin nature, has emphasized human depravity. Theologically interpreted, one might say that Chinese intuit the fact that humans were originally created good, made in the image of God. Thus, one could perhaps say that Chinese focus more on what is inherently human nature.

The West, on the other hand, focuses on the our sin nature, which is not an essential feature of having a human nature, since (a) Jesus was fully human but had no sin nature, (b) Adam had no sin prior to the Fall, and (c) we will not be less human in the new heaven and new earth, yet we will not have sin.

The West, on the other hand, focuses on the our sin nature, which is not an essential feature of having a human nature, since (a) Jesus was fully human but had no sin nature, (b) Adam had no sin prior to the Fall, and (c) we will not be less human in the new heaven and new earth, yet we will not have sin.

Sorting out the detailed thinking and the implications of these two views would take too much time. For now, I want to emphasize a couple of important and related points.

A Chinese Perspective on Parenting

First, Chinese see the potential in people for improvement. Therefore, Chinese emphasize hard work and self-discipline. (In truth, many Americans are no different in practice. The “American Dream” presumes the great potential of the rugged individual who can be anything he wants to be when he grows up.)

It’s not uncommon for an American parent to say, “Well, she just wasn’t born with that ability.” As a result, a girls parents may not push their daughter through those tough times required of any student trying to master a new skill, like playing piano or dance. It could of course work the other way. One could not work hard to develop a “natural” gifting precisely because a person takes that talent for granted.

The Chinese on the other hand see the interconnectedness of people and events. For some, it can lead to a sort of fatalism, so that one doesn’t even want to try a new challenge. However, for others, they know they must work incredibly hard to overcome the various factors that stand in the way to their success.

One’s view of human nature and community is a fundamentally theological and missiological issue. It is not simply “Are we born good or bad?” It’s a bit more nuanced, which the second point above about context illustrates.

Our Response

Christian pastors, missionaries, and theologians have to take these questions seriously. In the zeal to makes things simple, we may cover over a number of problems. We can’t treat Chinese like Americans, just as one could not treat a New Yorker like a Cajun from New Orleans.

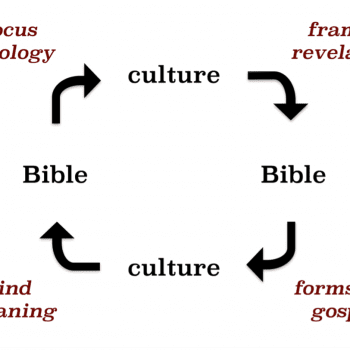

For all the talk about contextualization and global theology, I wonder how serious we actually are. Mission and evangelism books offer simple methods to start church planting movements with little consideration for how their formula may or may not work in another context. “Contextualization” (so called) in the States can often amount to nothing more than an alteration in music or esthetics.

Consider our task––we serve the one true Creator God in the midst of all the nations of the world. Do we really think this work should be simple?

I wonder if it might help the church if we would just be willing to complicate the whole process just a little bit.

Photo Credit: CC 2.0/wikipedia

Related articles

- Introducing My New Book, Saving God’s Face (www.patheos.com/blogs/jacksonwu)

- Tiger moms turning kids into robots (cnn.com)