If you are unfamiliar with the term “purity culture,” it is most often associated with the abstinence movement that emerged in full force during the 1990s (and whose influence is felt today). Joshua Harris became one of its most recognizable spokesmen; he authors the bestseller I Kissed Dating Goodbye. You might also recall organizations like “True Love Waits.”

If you are unfamiliar with the term “purity culture,” it is most often associated with the abstinence movement that emerged in full force during the 1990s (and whose influence is felt today). Joshua Harris became one of its most recognizable spokesmen; he authors the bestseller I Kissed Dating Goodbye. You might also recall organizations like “True Love Waits.”

Preaching a “Sex Prosperity Gospel”

The intentions of the movement are laudable. Church leaders wanted to protect their children from the pains that can come with premarital sex. They also wanted kids to have happy marriages free of guilt and shame. As with many things, the problem with purity culture was/is not its goals as much as the methods it used.

I have heard people say that purity culture preached a “sex prosperity gospel.” The basic message went something like this: If you don’t have sex before marriage, you will have wonderful marriages with amazing sex.

Naïvely, church youth bought the promises of purity culture. And, sadly, unintended consequences followed.

One Sin that Changes Who I Am

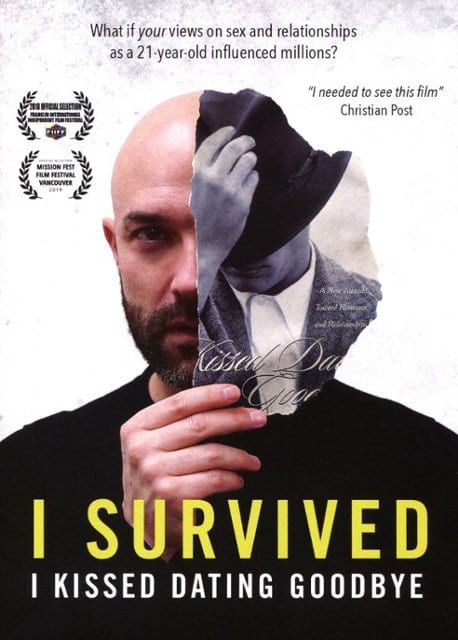

I recently saw the documentary “I Survived I Kissed Dating Goodbye.” In it, Joshua Harris faces his critics and reconsiders the legacy of his book. Around the 19-minute mark, Harris makes an astute observation. He says,

“There are all kinds of categories of sin where we sin and we don’t change our status, like you know, if you lie, you don’t say, “Oh well, I’m no longer, you know, a lying virgin or something….” [laughter] We just don’t think that way. We just say, “You know what? I sinned. I want to repent of that. I want to move forward.”

But with this issue, it’s like, if you have sex, you’re no longer a virgin, you know, it’s like your status has somehow changed. And I think that’s an emphasis on one particular sin out of the millions of ways that we can sin that I think is actually not healthy. It makes the focus not so much “Who am I in relationship to God, who loves and relates to sinners and shows grace to sinners.” It becomes this “Do I have this badge and this identity of being a virgin?”

And if I don’t have that, then I feel like I’ve lost something and I’m no longer as valuable…. I think that led a lot of us astray.”

In effect, purity culture conveyed the idea that this one particular sin— sex outside of marriage— would lead a person to perpetually being stained. This link between one sin and an altered identity has led to decades of turmoil for many people who have struggled to untangle sex and shame.

Thinking that Traps Us

How did the purity movement magnify one specific sin such that it seeming changed one’s identity in ways that other sins did not? I suggest two answers.

-

Idolatry

First, the movement subtly reinforced the idolatry it opposed. Harris underscores an irony. In short, the purity movement presents “sex as the most important thing to sell abstinence.” Christine Gardner, the author of Making Chasity Sexy, chronicles various ways that rallies and music were used to get people excited about sex only then to say, “Don’t have sex.”

These methods of purity culture infuse kids with idolatrous thinking that isolates one blessing above all others. It never dislodges the idolatry of sex. It isolates one blessing among others. In an odd way, “Don’t have sex” acts similarly to the command “Don’t think of a pink elephant.” The heightened attention and exaltation of sex undermine the movement’s own goals.

Physical intimacy is no longer seen within the larger plan and promise of God for creation. Such reductionism isolates and then privileges different parts of life. We begin to define ourselves in terms of one sin or social sphere.

-

Purity Language

Second, the movement exploited purity language without realizing the potent effect of the metaphor. For example, many kids in the 1990s publicly confirmed their decision to remain abstinent by wearing purity rings. Similar rituals continue today. In one documentary, we see families and communities hold galas where the girls wear white dresses to celebrate their virginity.

Richard Beck’s Unclean contains one of the most profound treatments on the relationship between morality and purity language (chapter 3, “Morality and Metaphor”). All metaphors assume a certain logic. Our minds often fail to notice the implicit logic one welcomes when accepting a certain metaphor.

When a person becomes “unclean” or “impure,” one needs a remedy. Unclean people attempt to regain their purity. However, virginity is not something that can be regained. Just as women cannot be “sort of pregnant,” neither can is someone a “sort of” a virgin. You are or you are not. There seems to be no remedy.

When “virgin” becomes a fundamental identity claim, what happens? Church kids who have sex before marriage then come to feel they have become moral lepers.

In the coming posts, I’ll further explore the power of purity language and the consequences of “purity culture.”