The articles here usually talk about theology or missions, often something where those topics intersect (like contextualization, honor, and shame). Yet, I hope to achieve more than dispense useful information about the Bible and missiology. Other desires also motivate what I write and how I do so.

I did not grow up in a Christian home. I was not “churched” from a young age. As I’ve followed Christ over the years, I’ve seen certain habits of thinking and interacting that are concerning. On the one hand, some people are too hesitant to disagree with one another, fearful of looking “unchristian” or causing disunity in the church. On the other hand, many people seem always to be looking for a fight. Any disagreement could be seen as a challenge to the Bible’s authority.

Accordingly, one hope I have for the church is that we would learn how to have the courage to disagree and the wisdom to do so well.

Without understanding how to disagree well, the church will never have unity, just mere conformity. Without civility amid differing convictions, the church need not worry about “the world” because it will become its own worst enemy. When it comes to ministry, we will struggle to find solutions to ongoing problems because we remain unteachable.

Responding to Argument Culture

This is why I think Meuhlhoff and Langer’s recent book Winsome Conviction: Disagreeing without Dividing the Church is so timely and important. This is not a book of platitudes and well-wishing. It’s packed with substantial insights and practical tips. (They also have a related podcast called, yes, “Winsome Conviction.”)

They lament the full-blown emergence of “argument culture” within the United States (a term used by Deborah Tannen), including the church. In their podcast, they quote Tannen saying,

“The Argument Culture urges us to approach the world and the people in it in an adversarial frame of mind, it rests on the assumption that opposition is the best way to get anything done. The best way to discuss an idea is to set up a debate. The best way to cover news is to find spokespeople who express the most extreme polarized views and present them as both sides. These all have their uses and their place, but they are not the only way, and often not the best way to understand and approach the world.”

“That a characteristic of the argument culture is you exclude listening and you exclude an attempt to understand the other person.… When you’re having an argument with someone, your goal is not to listen and understand. Instead you use every tactic you can think of, including distorting what your opponent just said in order to win the argument.”

This is the problem and context for which this book was written.

Agreeing to Disagree

What is the greatest threat to the church? According to Meuhlhoff and Langer, it’s quarreling (17), a cancer that destroys the church from within. In the Introduction, they suggest three ideas that run counter to much conventional thinking (5). They state,

- “We do not believe that strong convictions cause incivility.”

- “We will dispute the claim that convictions are about absolutes.”

- “We do not believe that all Christians will agree on all matters of conviction.”

In Romans 14, Paul affirms the legitimacy of personal convictions yet without equating a conviction with an absolute, universal norm or command. He also “does not even claim all viewpoints are equally valid” (25). While we might base our convictions on absolute commands, they should not be confused. We can change our convictions.

In the book, what is a “conviction”? They “are firmly held moral or religious beliefs that guide our beliefs, actions, and choices” (34). They tend to be implications of bigger ideas, not clear statements from the Bible itself.

Behind convictions are values. While Christians can generally agree about a set of values, they tend to disagree about which values should have priority, which have greater weight, and in what situations (41). Because convictions are so tied to our emotions, we can become overly protective of them, as though they were absolutes.

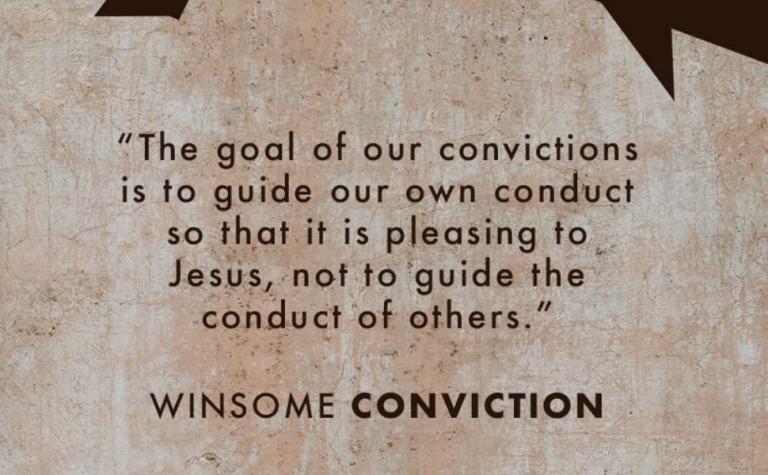

A problem grows whenever we “export” our convictions. Our judgments functionally absolutize our convictions. The authors add, “The goal of our convictions is to guide our own conduct so that it is pleasing to Jesus, not to guide the conduct of others” (30). Elsewhere, they speak about what happens in small groups and in discussions.

“The goal is to refine and deepen one another’s convictions… The goal is not to produce a single accepted conviction for the entire group” (46).

Two Questions

So now, it’s time to ask ourselves a few questions.

First, how are you caught up in “argument culture”? (After all, who among us can claim to be completely innocent?)

Second, which of your convictions might you be prone to treat as absolutes (which you’re likely to try exporting to others)?