A generation ago, Paul Hiebert popularized a way to describe three paradigms that people use to define and describe churches. One can intuitively see that the model has significant and practical implications; however, until recently, few people have attempted to tease them out.

This is where we should be grateful for Mark Baker’s new Centered-Set Church: Discipleship and Community without Judgmentalism.

Defining Three Paradigms

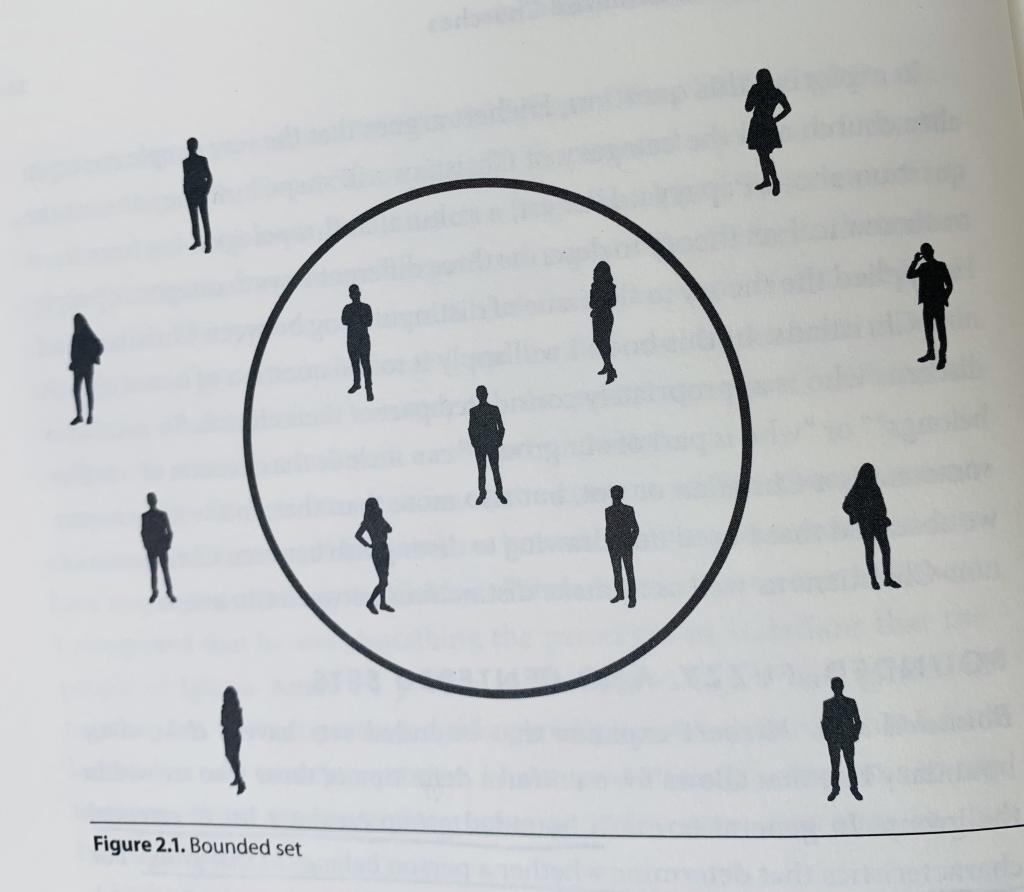

Three major paradigms represent how most people understand their local church (and the church more generally). First, conservative, traditionalist churches tend to be “bounded.” These “bounded set churches” are characterized by distinct criteria that determine who are insiders and who are outsiders.

Such markers of belonging might include faith statements or specific practices. These criteria are deemed essential to being a member of the group.

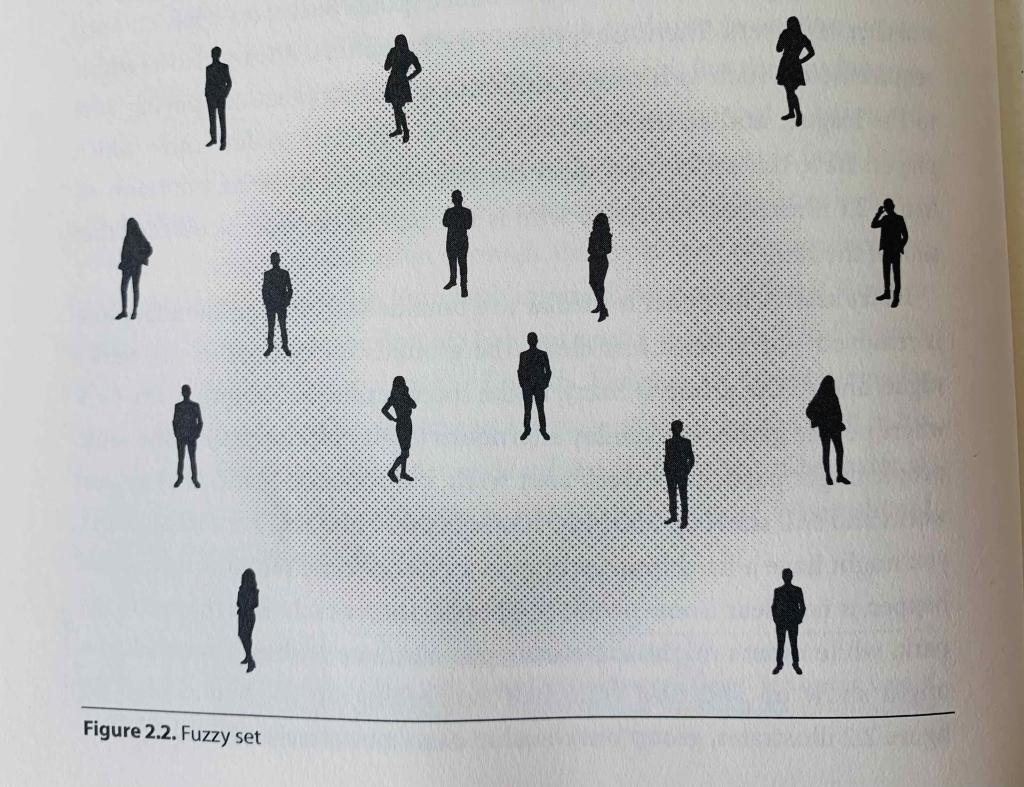

Second, some churches are “fuzzy set” communities. These churches abhor drawing lines that divide insiders and outsiders. There is hardly any clear basis for group identity. The hyper-emphasis on inclusion typically stems from their antipathy towards bounded set churches.

Baker advocates a third, alternative approach: centered-set churches. He says,

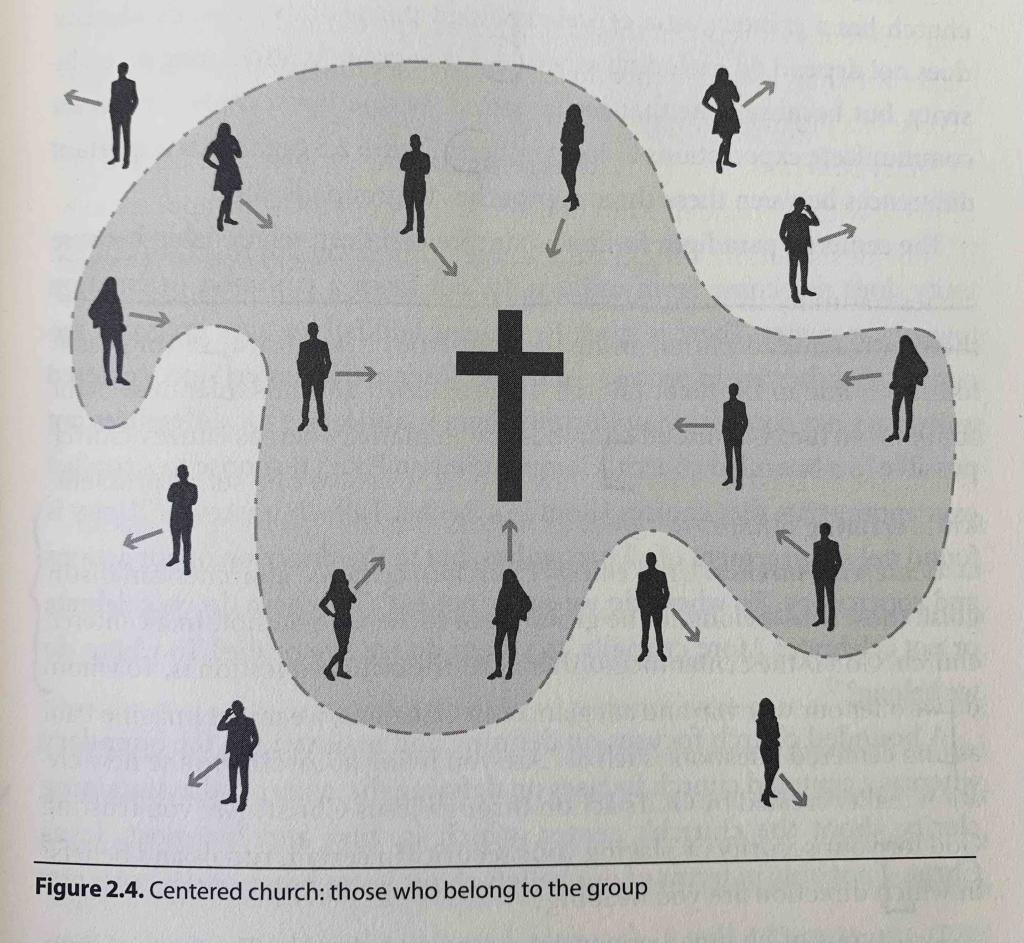

“Rather than drawing a line to identify people based on common characteristics, a centered set uses a directional and relation basis of evaluation. The group is created by defining a center and observing people’s relationship with the center… the set is made up of all who are oriented toward the center.” (p. 23)

The center-set paradigm defines everything and everyone around the question, “To whom do we offer our worship and allegiance?” (p. 26).

The above descriptions, of course, are simplifications. Baker delves more deeply into what constitutes each of these church types. In Centered-Set Church, he does an excellent job anticipating people’s objections and clarifying why these categories matter.

Orientation and Movement

Two features mark center-set churches–– orientation and movement. Understanding these two ideas helps us to appreciate this paradigm’s value and not respond with confusion and false assumptions.

First, let’s explain orientation. Members of a centered-set church are oriented on Jesus in a similar way that the planets of our solar system are oriented on the sun. This orientation unites people rather than their being conformed to one another according to various characteristics.

Second, centered-set church members seek to make movement toward Christ, their orienting center. They do not necessarily make progress at the same pace. Nevertheless, their ambition is to make steady movement in reflecting Christ more faithfully.

Some people misunderstand centered-set thinking by claiming that such churches have little concern for distinguishing Christians from non-Christians. Notice, however, how Baker’s Figure 2.4 (above) still marks out one group from another. While an implicit line exists,

“the line does not define the person’s relationship to the group. Rather, the line emerges by observing a person’s relationship to the center. If we erase the line, we still have the group… For a centered group, the emphasis is on defining the center and maintaining a relationship with the center.” (p. 29)

Undoubtedly, one will hear objections that “Christ” is too general a center. What if your view of Christ differs far too drastically from my perspective of him? What if our theologies diverge so much that we could not possibly worship the same person?

A Fantastic Analogy

Baker anticipates this concern and responds at length in the book. I’ll comment more in the next post. For now, it’s important simply to grasp a fundamental paradigm shift and then imagine its significance.

He offers a fantastic analogy worth our reflection. He writes,

“In the dry Australian outback, it is too expensive for ranchers to build and maintain fences that will contain cattle on their huge properties. So rather than building fences, they dig wells. Though their cattle will roam, they will not roam far, because they must keep returning to the well to drink water.” (p. 39)

With just this basic introduction, how might these three paradigms lead to different ways of being the church? It would be worth entering into a conversation this week, considering the fruit of being either a bounded-set, fuzzy-set, or centered-set church.