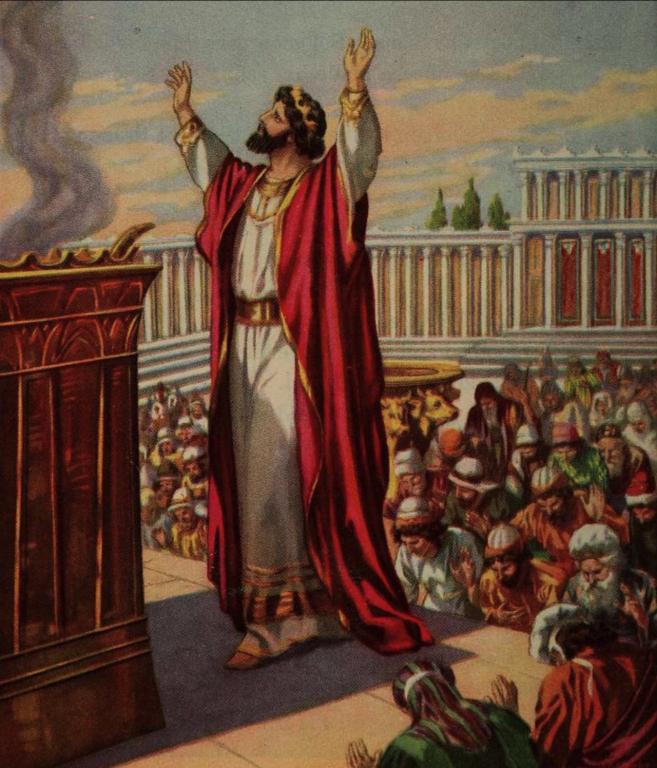

The Old Testament presents numerous examples of sacrifices, many of which can be understood as symbolic meals offered to God by His worshipers. From the solemnity of the Passover Lamb to the simple grain offerings, these sacrifices were not only acts of atonement but also deeply communal and spiritual experiences.

(Unfortunately, too few evangelicals talk about this OT background. For an exegetical deep dive into this topic, see The Cross in Context.)

Eating a Meal with God

Various scholars have observed how many biblical sacrifices are imbued with the symbolism of a meal. This imagery speaks to the intrinsic relationship between the divine and human, and more significantly, it underscores the reverence and adoration shown to God by His followers through this shared “meal.”

The term “meal” itself might evoke casual associations with our daily routines; however, in the biblical context, this connotation is significantly elevated. A meal shared with the divine is a profound expression of communal intimacy and a display of honor and reverence. Moreover, these “divine meals” are made possible by the worshipers who present their offerings as food to God.

Examples in Scripture

To unpack this idea, let’s consider some examples. In Leviticus 7:14-17, the bread is regarded as a “gift to the Lord.” The priest first eats the offering. Then, God seems to consume the meal in 7:17.

From this you shall offer one cake from each offering, as a gift to the Lord; it shall belong to the priest who dashes the blood of the offering of well-being. And the flesh of your thanksgiving sacrifice of well-being shall be eaten on the day it is offered; you shall not leave any of it until morning. But if the sacrifice you offer is a votive offering or a freewill offering, it shall be eaten on the day that you offer your sacrifice, and what is left of it shall be eaten the next day; but what is left of the flesh of the sacrifice shall be burned up on the third day.

Leviticus 21:6 says of the priests, “They shall be holy to their God, and not profane the name of their God; for they offer the Lord’s offerings by fire, the food of their God; therefore they shall be holy.” The Lord’s “food” in 21:6 is equated to the Lord’s “fire” (ʾišše). In Leviticus, the term describes each of the five main offerings and is equated with the bread elsewhere (cf. Lev 24:7; Num 28:2, 24).

Why use fire imagery? In effect, the burning fire transforms the sacrifice, lifting it to God. Therefore, God and people could have fellowship. Where did they eat this meal? In God’s dwelling place, his temple, or simply God’s “house.”

These observations run contrary to modern sensibilities. Still, God explicitly commands Israel to give him food. The Lord tells Moses,

“Command the Israelites, and say to them: My offering, the food for my offerings by fire [ʾišše], my pleasing odor, you shall take care to offer to me at its appointed time” (Numbers 28:2).

Ezekiel even appears to represent blood as a kind of drink given to God. Ezekiel 44:7 rebukes Israel’s leaders for

“admitting foreigners, uncircumcised in heart and flesh, to be in my sanctuary, profaning my temple when you offer to me my food, the fat and the blood. You have broken my covenant with all your abominations.”

To be clear, these offerings are symbolic gifts. Scripture does not claim that God needs food. In fact, Psalm 50:7-15 rejects the suggestion. The psalmist says,

Hear, O my people, and I will speak, O Israel, I will testify against you. I am God, your God. Not for your sacrifices do I rebuke you; your burnt offerings are continually before me. I will not accept a bull from your house, or goats from your folds. For every wild animal of the forest is mine, the cattle on a thousand hills. I know all the birds of the air, and all that moves in the field is mine. If I were hungry, I would not tell you, for the world and all that is in it is mine. Do I eat the flesh of bulls, or drink the blood of goats? Offer to God a sacrifice of thanksgiving, and pay your vows to the Most High. Call on me in the day of trouble; I will deliver you, and you shall glorify me.

The fact that Israel could misunderstand the sacrifices like this further confirms the above interpretation, that is, sacrifices served as symbolic food. Hendel says, “These meals dramatize the bonds of intimacy and distance that relate Israel to God. Table and altar are analogous in various ways, implicitly foregrounding the Israelites’ closeness to God.”[1]

Sharing Communal Meals

These examples highlight that the symbolic meals are an integral part of worship, an offering to God that simultaneously provides sustenance to the worshipers. Through this process, the bond between the divine and the faithful is reaffirmed, creating a mutually enriching experience.

But what happens when the offerings are of a non-animal nature, such as grain offerings? Here, too, we see the meal symbolism emerge. Leviticus 2 introduces the grain offering, a sacrifice made with fine flour, oil, and frankincense. This grain offering, much like the animal sacrifices, was ‘consumed’ partially by God through the act of burning on the altar, while the remainder served as food for the priests.

The burning of offerings on the altar and the rising smoke symbolize God’s receiving or, perhaps, consumption of the meal. Just as the family head in ancient cultures would partake of the best portions of a meal, so too the finest parts of the offering are given to God, acknowledging Him as the supreme head of the universal family.

Importantly, the communal aspect of these “meals” reinforces the communal nature of worship. The remaining portions of the grain offering were consumed by the priests, who represented the people before God. Hence, this offering both demonstrated the worshiper’s devotion and also played a vital role in maintaining the community’s spiritual leaders.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the concept of biblical sacrifices as symbolic meals encapsulates the profound relationship between God and His people. The shared “meal” signifies mutual sustenance, honor, and community—the worshiper offers a gift of sustenance to God, while also sustaining themselves and their community. It’s a tangible expression of devotion, showing that worship is not a mere act of ritual compliance but a deeply relational act of love and respect.

To conclude, biblical sacrifices’ portrayal as symbolic meals offers a rich, multi-dimensional understanding of the nature of worship. These sacrifices are not just transactions or obligations; they are shared meals—acts of communion that echo the deep, relational character of God, who desires more than our offerings: He desires our hearts.

This enduring lesson from Old Testament serves as a reminder for us today. As we come to God with our offerings, may we do so not out of duty but out of love, honoring Him as we would honor a cherished guest at our table, acknowledging Him as the provider of all good things, and expressing our deep gratitude and reverence for His abundant grace.

[1] Ronald Hendel, “Table and Altar: The Anthropology of Food in the Priestly Torah,” in To Break Every Yoke: Essays in Honor of Marvin L. Chaney, ed. R. B. Coote and N. K. Gottwald (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2007), 145.