Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Second Discourse on the Origins of Human Inequality offers a critical examination of the human condition, tracing the roots of inequality back to the earliest stages of social development. (See my previous post for a critique of his individualism.)

As flawed as his work is, Rousseau rightly observes that competition and the lust for respect are foundational elements that generate inequality and lead to varied social ills. This post explores how Rousseau’s critique of competition and the drive for recognition exposes underlying dynamics that still plague contemporary societies.

The Birth of Competition

In his Second Discourse, Rousseau reflects on the transformation of human beings from isolated individuals living in a “state of nature” to members of a stratified society. According to Rousseau, in the state of nature, humans were peaceful, free, and indifferent to the status of others. They were driven by basic needs such as hunger, shelter, and rest. However, as civilization progressed, human beings began to live in larger groups, and with this communal existence came new challenges— particularly competition for resources, status, and recognition.

Though known as a political writer, Rousseau argues,

“even without the government becoming involved, any quality of prestige and authority becomes inevitable among private individuals as soon as… they are forced to make comparisons among themselves and to take count of the differences they discovered in the continual use, they have to make of one another.”

Rousseau argues that the desire for respect and esteem is not natural to humans but arises in the context of society. He says it became necessary to be acknowledged as somebody, to make oneself known by doing deeds, and to compare oneself to others. In this new social setting, individuals began to compare themselves to others and developed a sense of pride, leading to envy and rivalry.

It is this relentless comparison that Rousseau identifies as the root of inequality— the need to prove oneself better, to be more respected, or to be richer than one’s neighbor.

The Pitfalls of Social Esteem

The drive for respect, according to Rousseau, introduces a harmful aspect of human psychology: the insatiable desire to outdo others.

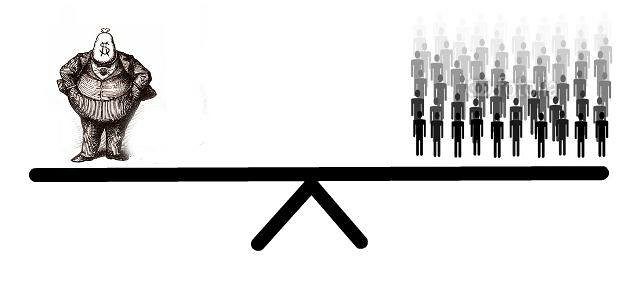

This competitive spirit led to an array of negative outcomes, including the establishment of social hierarchies and the oppression of those deemed inferior. By constantly comparing themselves with others, individuals sought ways to dominate and distinguish themselves, leading to increasing disparities in wealth and power. The desire for esteem was linked to the emergence of property ownership, and from there, inequalities in power and privilege became entrenched.

In this context, Rousseau asserts, “The first man who, having enclosed a piece of land, thought of saying, ‘This is mine,’ and found people simple enough to believe him, was the real founder of civil society.” The establishment of property was not merely the birth of economic inequality but also the beginning of moral corruption, as it institutionalized the competitive drive.

Ownership became synonymous with respect, and those who lacked property were marginalized. This marked a departure from the simplicity of the state of nature, where humans lived independently and without concern for their relative status.

Social Ills from Competition

Rousseau’s understanding of competition has implications for understanding the problems facing modern society. The obsession with social status and material wealth is seen today in the persistent inequalities that characterize many societies. The drive to accumulate wealth and to be recognized as “successful” pushes individuals to prioritize personal gain over the welfare of others. This drive often leads to a breakdown of social cohesion and an erosion of communal values, as the pursuit of individual success fosters alienation, greed, and distrust.

Rousseau warns that society’s emphasis on competition inevitably produces losers. When individuals are constantly measured against one another, those who cannot keep up are left behind and stigmatized as failures. This dynamic is evident today in the way we treat the economically disadvantaged, where poverty is often perceived as a personal failing rather than a systemic issue.

The pressure to compete has led to increased stress, anxiety, and a deepening sense of disconnection— problems that Rousseau foreshadowed as inherent in a society built on comparison and rivalry.

Moreover, Rousseau’s critique of competition extends to the political realm. He understood that the pursuit of power and status was not limited to individuals; it also manifested within institutions. Nations compete with one another in the quest for dominance, resources, and influence, often leading to conflict and war. This competitive nationalism has far-reaching consequences, from colonial exploitation to contemporary geopolitical tensions. Rousseau’s insights into the destructive consequences of competition reveal the dangers of a worldview that prizes winning above all else.

The False Promise of Progress

One key insight from Rousseau in the Second Discourse is that progress, as it is typically conceived, is not synonymous with the betterment of human life.

The technological advancements and economic growth that often define “progress” are not necessarily aligned with the well-being of individuals or societies. Rather, progress has historically served to exacerbate inequalities by amplifying the differences between those who have access to resources and those who do not.

Rousseau’s understanding of competition reveals that the fruits of progress—wealth, status, and power—are unevenly distributed, leaving many worse off despite apparent societal advancements.

Rousseau’s critique of progress is particularly relevant in our current era of globalization and digital technology. While advances in technology have connected the world in unprecedented ways, they have also introduced new forms of competition. Social media platforms, for instance, have become gladiatorial arenas for individuals to compete for attention, validation, and popularity.

The constant pressure to present a curated image of success has fostered a culture of comparison, contributing to declining mental health and deepening feelings of inadequacy. Rousseau’s analysis helps us understand how the relentless pursuit of respect and recognition can lead to widespread social ills, even in an age that celebrates connectivity and progress.

The Cost of Status-Seeking

Rousseau’s examination of the drive for social esteem also exposes the ethical costs of status-seeking behavior. When individuals become fixated on gaining respect and recognition, they often do so at the expense of their moral values. Rousseau argues that this desire leads people to act inauthentically, adopting behaviors that may gain them approval but that are ultimately hollow and self-serving.

The pursuit of respect becomes a performance. Genuine virtue is sacrificed in favor of appearances. This critique resonates today, as many people struggle with the pressure to conform to societal standards of success and to engage in performative displays of morality or virtue signaling.

The ethical cost of competition is also evident in the economic realm, where the pursuit of profit often leads to the exploitation of workers, environmental degradation, and the perpetuation of unjust practices. Rousseau’s analysis suggests that when competition is left unchecked, it encourages behavior that is not only detrimental to others but also dehumanizing to those who engage in it.

By reducing relationships to transactions and valuing individuals based on their economic contributions, competition erodes the social fabric and undermines the very idea of a just society.

Moving Beyond Competition

Rousseau’s insights into the corrosive effects of competition and the lust for respect provide a powerful critique of the values that underpin modern society. While Rousseau’s idealization of the state of nature may be impractical as a model for contemporary living, his emphasis on the dangers of competition offers an important corrective to the excesses of individualism and the relentless pursuit of success.

Instead of defining worth through comparison, Rousseau invites us to consider a society that values cooperation, empathy, and the well-being of all its members.

A more equitable society, he suggests, would recognize the importance of shared interests over individual ambition. By fostering a sense of community and mutual support, we can begin to address the social ills that arise from competition and the pursuit of status. His vision calls us to reevaluate the metrics by which we measure success and to cultivate values that prioritize human connection and collective flourishing over the fleeting rewards of status and respect.

Conclusion

I find myself appalled at most of what Rousseau says in Second Discourse on the Origins of Human Inequality. However, he does provide a compelling critique of the social (status-oriented) forces that drive inequality and social ills. His analysis of competition and the lust for respect reveals the deep-seated problems inherent in a society built on comparison, rivalry, and the pursuit of status.

While Rousseau’s vision of an ideal society may not offer a practical blueprint for modern living, his critique serves as a vital reminder of the costs associated with unchecked competition. By recognizing the dangers of status-seeking and embracing values that promote solidarity and empathy, we can work towards building a flourishing society that is more just and humane.