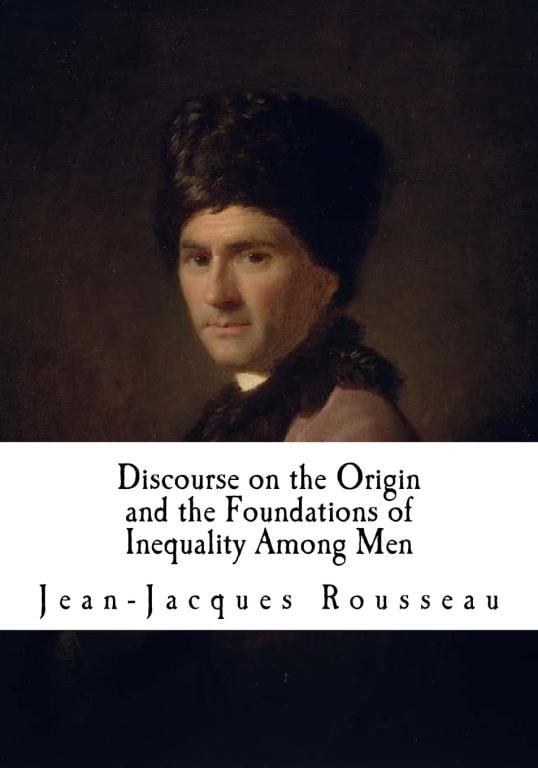

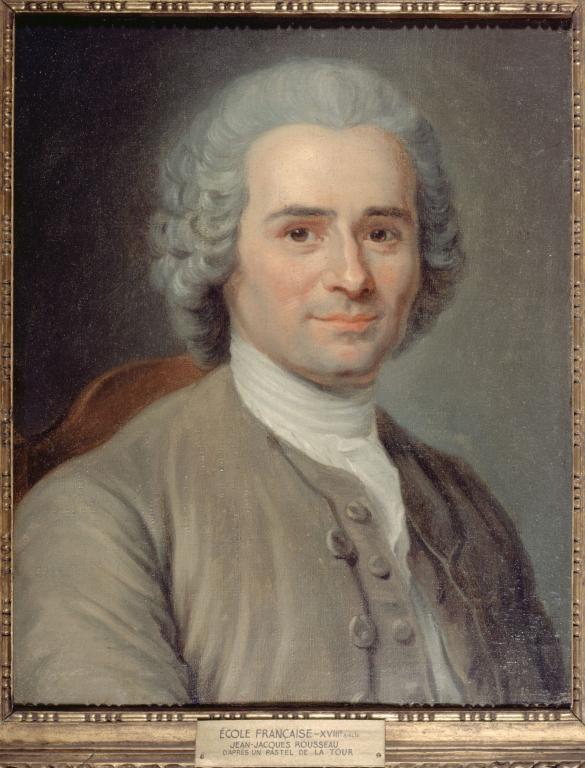

Jean-Jacques Rousseau is often celebrated as a champion of liberty, individualism, and natural human goodness. In his Second Discourse on the Origins of Human Inequality, Rousseau tries to expose the dangers of social inequality by tracing the root of human misery to the onset of civilization.

While I find his writing abysmally naive and self-contradictory, he does give voice to some of the worst inclinations in the modern West. His famous claim, “Man is weak when he is dependent and he is emancipated before he is robust,” epitomizes a particular strain of Enlightenment thinking that is deeply problematic.

This post critiques Rousseau’s perspective, emphasizing just one way that his vision of human freedom is flawed and highlighting its unintended consequences for society.

Rousseau and Enlightenment Thought

Rousseau’s Second Discourse is fundamentally a critique of civilization and an idealization of a pre-social “state of nature.” He posits that human beings, in their natural state, were solitary and free, unencumbered by the artificial dependencies that characterize contemporary society. Civilization, he argues, led to corruption by creating artificial needs and dependencies on others, as symbolized by property, social norms, and institutions.

Rousseau’s philosophy is representative of Enlightenment thinking, which often portrayed human beings as inherently rational and society as the corrupting force that prevents people from realizing their full potential. (Again, I find his argument embarrassingly illogical, yet many others drool over his conclusions.)

Rousseau’s sentiment that “Man is weak when he is dependent” reflects a problematic understanding of what it means to be human. Dependency is not only an essential characteristic of human life; it is also the foundation of social bonds and moral obligations. To Rousseau, dependency equals weakness, which implies that true freedom must be grounded in uncompromising independence.

Such a worldview glorifies an ideal of absolute self-sufficiency that overlooks the importance of interdependence—a critical flaw that carries over into how we think about social and political issues today.

The Emancipation Paradox

Rousseau’s claim that “man is emancipated before he is robust” suggests a paradox inherent in his thinking. He imagines an idealized emancipation, where individuals break free from all forms of external control before they can engage in a mature, self-directed life. In reality, human beings become capable through the experience of relational interdependence.

As infants, we are utterly dependent on caregivers; it is this dependency that allows us to become robust, capable adults. Rousseau’s vision assumes a linear progression— as though emancipation somehow occurs without the prior nurturing that creates robustness in the first place.

This logic, when taken to its extreme, has troubling implications for how we perceive freedom. The idea that true freedom requires shedding all forms of dependency disregards the deeply relational nature of human existence. Rather than being a sign of human frailty, dependency fosters empathy, mutual support, and the capacity for growth.

Rousseau’s emphasis on emancipation encourages a false ideal— one that values atomistic individualism over collective well-being.

A Critique of Enlightenment Individualism

Rousseau’s troublesome legacy can be traced to his foundational assumptions about human nature, which carry over into modern notions of individualism. By emphasizing the state of nature as a pure and inherently free state, Rousseau reinforces the idea that human beings are only truly human when they stand alone. Such a notion is a baseless figment of his imagination.

He envisions utopian freedom as a return to a supposed original autonomy—free from the entanglements of society and culture. While this conceptualization of freedom appears liberating, it invariably turns into a form of hyper-individualism that undermines the social contract that binds communities together.

Here’s a little more background to contextualize Rousseau.

He writes, “The first man who, having enclosed a piece of land, thought of saying, ‘This is mine,’ and found people simple enough to believe him, was the real founder of civil society” (Second Discourse). Here, Rousseau explicitly ties the origins of inequality to the birth of private property and the establishment of rules governing ownership and power.

This critique remains powerful in revealing how material inequalities perpetuate social stratification, yet his solution—a return to a purer, more autonomous human existence—is unhelpful in addressing the intricacies of our society. It suggests that the ideal state for humanity is one free from relational ties, where any dependence represents a loss of freedom.

This perspective has contributed to contemporary issues such as the valorization of self-made success and the stigmatization of those who require help, whether due to economic hardship, disability, or age. If we accept Rousseau’s vision, individuals are deemed worthy only when they can act without aid from others, a perspective that leads to social alienation and a lack of collective responsibility.

The claim that dependency equals weakness is reflected today in the way societies treat vulnerable populations, often prioritizing individual autonomy over social welfare. In this sense, Rousseau’s thought is the seed of a Western ideology that problematically celebrates radical independence at the expense of compassion and mutual aid.

Human Flourishing Requires Dependency

Rousseau’s critique of dependency also lacks an appreciation for the positive dimensions of social ties. Human flourishing, as the Bible, Aristotle, and countless others argue, occurs within a community where individuals engage with others in meaningful ways.

His denouncement of dependency obscures the reality that relationships are essential for well-being.

Individuals cannot develop virtues, moral understanding, or even basic human capacities in isolation. Rousseau’s idealized human—emancipated, free from dependence—becomes a ghost of sorts, unable to fully engage in the richness of human experience.

Take, for instance, Rousseau’s romanticization of the “noble savage”—a figure who lives free from the burdens of social institutions. While this image resonates with many as a critique of the corrupting influence of modernity, it ultimately paints a one-dimensional portrait of human nature that undervalues community, cooperation, and shared responsibility.

The vision is one of freedom without commitments, a simplistic reduction of what human life truly entails. It’s a sad one at that.

In dismissing the role of relational ties, Rousseau’s Second Discourse ends up undermining the very conditions that make authentic freedom possible; namely, the nurturing social structures that allow individuals to thrive.

The Contemporary Relevance of Rousseau’s Ideas

The impact of Rousseau’s individualism is still seen in contemporary debates over individual rights versus social obligations. In modern Western societies, the rhetoric of self-reliance and independence often takes precedence over communal considerations. This is evident in discussions about social welfare, healthcare, and economic policy, where dependency is frequently portrayed as a moral failing.

Rousseau’s vision of freedom— one that prioritizes emancipation from all forms of external influence— contributes to this misguided valorization of autonomy.

In contrast, a more balanced perspective would recognize that dependency is not inherently antithetical to freedom. In fact, meaningful freedom emerges from interdependence and a recognition of mutual vulnerability. Social systems that emphasize collective welfare, such as universal healthcare or public education, reflect the understanding that human beings are inherently interconnected. The Enlightenment’s focus on individual autonomy, says Rousseau, fails to appreciate this fundamental truth.

Ultimately, Rousseau’s perspective on dependency and emancipation reflects the limitations of Enlightenment rationalism when taken to its extreme. By imagining a world in which people must shed all dependency to become truly free, Rousseau unwittingly sets up an impossible ideal. His critique of inequality, while valuable in exposing the corrupting influence of societal hierarchies, misses the mark when it comes to understanding how humans thrive together.

Freedom is paradoxically often found not in isolation but in community—in relationships where mutual dependency fosters resilience, empathy, and true human flourishing.

Conclusion

Rousseau’s Second Discourse offers a powerful critique of civilization and inequality, yet his understanding of freedom as emancipation from dependency is fundamentally flawed. It reflects an unfortunate strand of Enlightenment thinking that idolizes self-sufficiency at the expense of interdependence.

This worldview, which confuses individuality and individualism, contributes to a modern society that values autonomy over care, individual rights over social responsibilities, and independence over empathy. As we consider Rousseau’s legacy today, we must challenge this notion that dependency equates to weakness and recognize that true human flourishing comes from embracing, rather than rejecting, our connections to one another.