A common phrase in contemporary evangelical theology is “Jesus died the death I deserve.” You’ll hear it in sermons, worship songs, and theological discussions. It’s meant to capture the heart of the gospel— that Christ suffered punishment in our place. But what if this seemingly biblical phrase actually distorts the very thing it’s trying to explain?

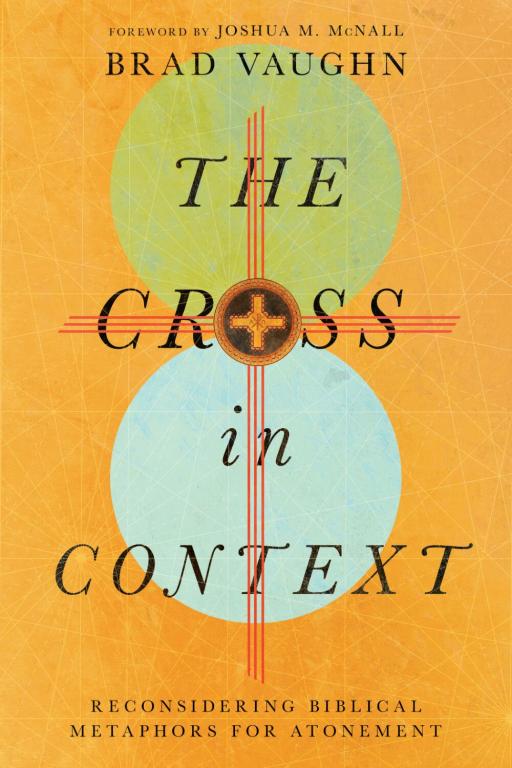

In writing The Cross in Context: Reconsidering Biblical Metaphors for Atonement, I became convinced that this formulation contains a fundamental category error that undermines both the logic of divine justice and the beauty of what Christ actually accomplished. The problem isn’t just theological nitpicking; it’s that we’ve confused payment with punishment, creating contradictions that weaken our understanding of the cross and limit our ability to communicate the gospel across cultures.

The Logical Contradiction in Penal Substitution

The standard evangelical explanation goes like this: sin creates a debt before God that demands punishment, so Christ bears that punishment in our place. But here’s the problem—this conflates two entirely different concepts: debt and punishment.

In any coherent system of justice, payment satisfies debt, while punishment is the consequence when debt goes unpaid. You don’t pay a debt and go to prison for failing to pay it. If Jesus truly “paid” our debt through his sacrifice, then additional punishment becomes not just unnecessary but unjust. As I’ve argued elsewhere, “If Jesus already settled our debt, God no longer should punish us… Otherwise, God would accept our payment, yet still punish us. This is unjust.”

This isn’t merely a theoretical problem. It distorts our understanding of God’s character. It suggests that divine justice is purely punitive, requiring suffering even when restitution has been made. But biblical justice, especially in the Old Testament context, is primarily relational and restorative, aimed at repairing relationships and restoring honor rather than simply inflicting deserved pain.

The Resurrection Problem

There’s another logical issue: if Christ truly died “the death I deserve,” then why is he raised? The death that sinners deserve, according to Romans 6:23 and Revelation 20:14, is eternal death— permanent separation from God. Yet Jesus is vindicated, exalted, and restored to divine presence (Philippians 2:9-11). His resurrection signifies divine approval, not divine punishment.

This creates an inescapable tension. If Jesus bore the punishment I deserve (= eternal estrangement from God), then resurrection becomes theologically incoherent. The only way to preserve the integrity of the resurrection is to conclude that Jesus’ death was not punitive in a retributive sense, but rather the fulfillment of his mission of obedience.

Consider Jesus’ actual words from the cross: “Into your hands I commit my spirit” (Luke 23:46). This echoes Psalm 31:5 and reflects trust, not abandonment. Jesus doesn’t cry out in despair at divine rejection—he entrusts himself to the Father. This is incompatible with the logic of punitive substitution.

What Kind of Death Did Jesus Actually Die?

If we step back from the punishment framework, a different picture emerges. Jesus’ death saves not because of the suffering involved, but because of the life that led to it. His death is the culmination of perfect covenantal loyalty—what I call “the death I couldn’t die.”

Paul frames this precisely in Philippians 2:8-11, “He humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death—even death on a cross. Therefore, God highly exalted him…” Notice the logic: God vindicates Jesus not because he absorbed punishment, but because he fulfilled the covenant through self-emptying obedience.

This obedience pattern runs throughout the New Testament. Hebrews says Jesus “offered himself without blemish to God” (9:14), language drawn directly from Levitical purity laws where only unblemished offerings appropriately honor God. In John’s Gospel, Jesus explicitly frames his death as glorification: “Now is the Son of Man glorified, and God is glorified in him” (13:31).

Jesus’ death is unique not because of divine wrath poured out on him, but because of the perfect life behind it. No sinful human can offer what Christ does (i.e., an entire existence devoted to the Father in complete righteousness). While our deaths are the wages of sin, Christ’s death is the fruit of devotion. It’s not retribution but representation, not condemnation but consecration.

Sacrifice as Gift, Not Penalty

This reframing aligns perfectly with how the biblical sacrificial system actually works. The Levitical system focuses on the value of the gift, not the suffering of the victim. Offerings must be “without blemish” (Leviticus 1:3, 10); the animal’s perfection, not its pain, makes the gift acceptable.

Sacrifices function as valued offerings that restore God’s honor and repair relationships, not as condemned scapegoats absorbing divine fury. They act as “public confessions of need and sin” where “the giver admits his offense, expresses repentance, and acknowledges that he needs forgiveness.” The act is inherently relational—an expression of allegiance, not a mechanism of retribution.

This is why Christ’s atonement is consistently described in gift and devotion language: “Christ gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God” (Ephesians 5:2). The key concept is gift—a costly, voluntary act of love and loyalty whose value satisfies divine justice by restoring the honor due to God.

Reframing Key Texts

Consider Galatians 3:13: “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us.” Rather than absorbing divine punishment, Christ enters the covenantal defilement and exclusion that characterized Israel’s exile. As Israel’s representative king, he overcomes this curse through obedience and resurrection, not by being punished in our place.

Similarly, Romans 3:25 describes Christ as a hilastērion—often translated “propitiation” but better understood as “mercy seat,” the cover of the ark where atonement was made. Christ becomes the new mercy seat, the place where God meets his people, and relationship is restored. The blood of Christ, like blood applied to the ark, signals access to God, not appeasement of divine rage.

The Better Substitution

This doesn’t eliminate substitution; it reframes it. Christ substitutes for us not by absorbing our fate but by fulfilling our calling. He becomes what we could not: one who glorifies God perfectly through faithful life and death. This preserves substitution while grounding it in covenantal categories of honor, loyalty, and reconciliation rather than legal categories of guilt and punishment.

Jesus doesn’t merely “take the hit” for sinners. He offers up the life and death they could never give. His gift satisfies divine justice not by absorbing divine fury but by restoring the glory due to God’s name.

Why This Matters

This reframing has profound implications. It presents a God whose justice aims at restoration rather than retribution, whose wrath is appeased by honor-giving gifts rather than punishment-absorbing victims. It explains why the Father exalts rather than abandons the Son. And it provides a more coherent foundation for Christian discipleship—we’re not merely shielded from punishment but invited to participate in Christ’s life of faithful devotion.

Perhaps most importantly, this model speaks with clarity across cultures, especially in honor-shame contexts that characterize much of the global church. Legal metaphors of guilt and punishment often confuse people in cultures where honor, kinship, and relationships are primary moral categories.

Jesus didn’t die the death I deserve. He died the death I couldn’t die— offering perfect honor where I could only bring shame, perfect loyalty where I could only offer betrayal, perfect reconciliation where I could only create alienation. That’s not less than penal substitution—it’s far more beautiful and biblically grounded.

The gospel isn’t that God found someone to punish instead of me. The gospel is that God found someone faithful when I was not, and through union with him, I too can become what I could never be on my own: one who honors God through obedience, even unto death.

For a deep dive into the biblical arguments supporting this post, see The Cross in Context: Reconsidering Biblical Metaphors for Atonement.