The big picture is this: profit requires labor, labor requires laborers, white North Americans wanted profit, they needed laborers, and African slaves became their laborers.

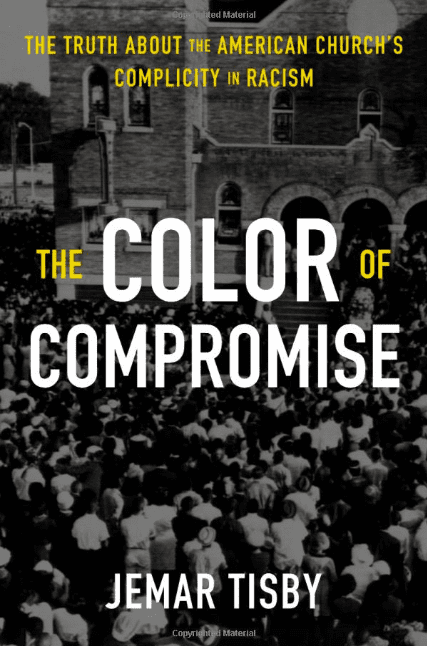

Not all at once, claims Jemar Tisby in his new book, The Color of Compromise. Indentured servants and laborers over time became slaves, and along with this shift was the connection of blackness to inferiority and whiteness to superiority.

My understanding of the history of slavery is that blackness was connected to slavery in about the 6th Century at the hands of Arab/Muslim profit-making and slaves from Africa were shipped into the Arab countries. Tisby’s focus is not that history but how race was connected to slavery in the Americas — from North to the West Indies to Central and South America.

In “Christian America,” Christianity itself was adapted to establish permanency in slavery rather to see slaves as brothers and sisters — siblings — in Christ. Christianity then did not emancipate slave bodies but liberated the soul while keeping the body in slavery.

So slave laws became common in North America:

As slavery became more institutionalized, more rules regulated its practice. By the mid-seventeenth century, colonies began developing “slave codes” to police African bondage. The codes determined that a child was born slave or free based solely on the mother’s status. They mandated slavery for life with no hope of emancipation. The codes deprived the enslaved of legal rights, required permission for slaves to leave their master’s property, forbade marriage between enslaved people, and prohibited them from carrying arms. The slave codes also defined enslaved Africans not as human beings but as chattel—private property on the same level as livestock.

Race is a social construct; it was tied to Christianity at times:

In The Baptism of Early Modern Virginia, historian Rebecca Anne Goetz explains how Europeans on the Atlantic coast of North America developed religious and racial categories in tandem. At first, colonists debated whether Africans were capable of becoming Christians. They adhered to a concept that Goetz calls “hereditary heathenism.” Just as parents passed down physical characteristics to their children, they also passed down their religion. Hereditary heathenism tethered race to religion. From their earliest days in North America, colonists employed religio-cultural categories to signify that European meant “Christian and Native American or African meant “heathen.” Over time, these categories simplified and hardened into racial designations.

Critical in this history was the challenge of the Bible’s message of equality and siblingship between all Christians, and critical here is that race was not tied to superiority in the Bible, so a challenge was at hand:

Even though European missionaries sought to share Christianity with indigenous peoples and Africans, social, political, and economic equality was not part of their plan. Missionaries carefully crafted messages that maintained the social and economic status quo. They truncated the gospel message by failing to confront slavery, and in doing so they reinforced its grip on society.

Motives for conversion were checked:

Francis Le Jau … When Le Jau was able to persuade African slaves to adopt the Christian religion as their own, he confirmed their profession by baptizing them. The vows he made the slaves recite show how European missionaries maintained a strict separation between spiritual and physical freedom. “You declare in the presence of God and before this congregation that you do not ask for holy baptism out of any design to free yourself from the Duty and Obedience you owe to your master while you live, but merely for the good of your soul and to partake of the Grace and Blessings promised to the Members of the Church of Jesus Christ.

Baptism, it was regulated, did not emancipate slave bodies from slavery:

The heading reads, “Key Slavery Statutes of the Virginia General Assembly,” and cites a law enacted in September 1667. … On the question of whether baptism would render slaves free, the Virginia General Assembly decided, “It is enacted and declared by this Grand Assembly, and the authority thereof, that the conferring of baptism does not alter the condition of the person as to his bondage or freedom.” This statute encouraged white enslavers to evangelize their human chattel since baptized slaves would not be freed. In the words of the assembly, “Masters, freed from this doubt, may more carefully endeavor the propagation of Christianity by permitting children, though slaves, or those of greater growth if capable, to be admitted to that sacrament.”

So from the beginning of American colonization, Europeans crafted a Christianity that would allow them to spread the faith without confronting the exploitative economic system of slavery and the emerging social inequality based on color.

Christianity served as a force to help construct racial categories in the colonial period. A corrupt message that saw no contradiction between the brutalities of bondage and the good news of salvation became the norm. European missionaries tried to calm the slave owners’ fears of rebellion by spreading a version of Christianity that emphasized spiritual deliverance, not immediate liberation. Instead of highlighting the dignity of all human beings, European missionaries told Africans that Christianity should make them more obedient and loyal to their earthly masters.