He will swallow up death in victory; and the Lord God will wipe away tears from off all faces (Is 25:8)

Ben Witherington III, Isaiah Old and New, sees later Isaiah 14-39 coming from the time of the historical Isaiah, the prophet in Judah through the time of Hezekiah, before the fall to Babylon. This section opens with oracles of woe and judgment against the nations and Judah, continues with such oracles interspersed with oracles of redemption and victory, and finishes up with a historical narrative recounting the miraculous deliverance of Jerusalem from Sennacherib, King Hezekiah’s illness and healing, and his rather foolish display of all his wealth to the envoys from Babylon.

Ben Witherington III, Isaiah Old and New, sees later Isaiah 14-39 coming from the time of the historical Isaiah, the prophet in Judah through the time of Hezekiah, before the fall to Babylon. This section opens with oracles of woe and judgment against the nations and Judah, continues with such oracles interspersed with oracles of redemption and victory, and finishes up with a historical narrative recounting the miraculous deliverance of Jerusalem from Sennacherib, King Hezekiah’s illness and healing, and his rather foolish display of all his wealth to the envoys from Babylon.

Many (perhaps most) scholars will argue that this section dates from a later time, after the fall of Jerusalem and exile, at least the material in chapters 24-27. Witherington argues that this is primarily because they see the hope of resurrection in Isaiah 25 and 26 as reflecting ideas from a much later era. Isaiah, the argument goes, would not have spoken of resurrection. Witherington counters that it is hard to pinpoint the emergence of an idea with any accuracy – especially in a time and place with relatively little written record and that the history of ideas shows that they wax and wane. Although later editors may have made some insertions leading to the text we have, there is no strong reason to doubt that these oracles date to the historical Isaiah.

It is to these oracles of hope that we turn. Specifically to Isaiah 25-26, 29, and 35. Quotes, allusions, and other references to these sections are quite important in the New Testament. Following Isaiah 25:8 quoted at the top of this post, Isaiah 26:19 is quite specific about resurrection:

Your dead will live;

Their corpses will rise.

You who lie in the dust, awake and shout for joy,

For your dew is as the dew of the dawn,

And the earth will give birth to the departed spirits. (26:19)

There is some ambiguity in the translation here, the NIV has “their bodies” and the NASB quoted above has “their corpses” but Witherington in a footnote says it should be “my corpses.” In fact, the Complete Jewish Bible (see Bible Gateway) has “Your dead will live, my corpses will rise.“

About these sections, Witherington writes:

Indeed, the reason phrases and ideas from Isaiah 26 show up on the lips of Jesus in Luke 7 and Isaiah 25 on the lips of Paul in 1 Corinthians 15 is precisely because they are taken to enunciate the notion of resurrection from dead even more clearly that what is said in Isaiah 40-66. (p. 127-128)

Here from the mouth of Isaiah we see the seeds of the ultimate victory through resurrection. Witherington goes on to argue:

Here then we find the notion of death being swallowed up by the Author of Life, God, and in addition we find out that the form this will take is bodily resurrection of “my corpses,” those which belong to God. (p. 128)

The reference to “my corpses” signifies the resurrection of God’s people. The ideas contained in these passages play an important role in the New Testament portrayal of the gospel.

Isaiah 34 and 35 turn to God’s wrath against the nations (34) and to the liberation of God’s people (35). We have here “the themes of judgment on Israel’s foes and redemption for God’s people.” (p. 132) Although chapter 35 starts with the parched land bursting into bloom, the emphasis is on the people and the return of the redeemed.

Strengthen the feeble hands,

steady the knees that give way;

say to those with fearful hearts,

“Be strong, do not fear;

your God will come,

he will come with vengeance;

with divine retribution

he will come to save you.”

Then will the eyes of the blind be opened

and the ears of the deaf unstopped.

Then will the lame leap like a deer,

and the mute tongue shout for joy.

…

And a highway will be there;

it will be called the Way of Holiness;

it will be for those who walk on that Way.

The unclean will not journey on it;

wicked fools will not go about on it.

No lion will be there,

nor any ravenous beast;

they will not be found there.

But only the redeemed will walk there,

and those the Lord has rescued will return.

They will enter Zion with singing;

everlasting joy will crown their heads.

Gladness and joy will overtake them,

and sorrow and sighing will flee away. (vv. 3-6, 8-10)

Witherington emphasizes that God is the redeemer here. There are at least two important aspects to this. First – nowhere in Isaiah is there a call to arms. Rather there is a call to turn to God and to rely on God.

Notice that we do not have a promise here that God will arm his people and teach them to fight. To the contrary, they are being told, “‘vengeance is mine; I will repay’ says the Lord” (cf. Isaiah 24:21-25:5; 34:8; 43:4; 48:20; 49:24, 25; 62:11). This theme is present throughout the book of Isaiah, however many hands may have contributed to it. (p. 133)

The theme is picked up in Revelation. According to Witherington:

Rather than a call to arms, Revelation is a call to say farewell to arms, and to leave justice in the hands of God, and to be prepared to die for one’s faith. This is called conquering. (p. 134)

Second, the healing of the people (blind, deaf, lame) has a spiritual aspect – but it is also a physical healing. There is a complete regeneration of the land and of the people.

Salvation must be seen in its holistic sense involving body and human spirit, involving the individual and the society, involving creation and creatures. … Here we should remember the promise of the shoot that comes out of the root in the dead stump of Jesse. God wants a whole new leadership for God’s people going forward. (p. 134)

Looking ahead to the topic of our next post – on the use of Isaiah 13-39 in the New Testament – it is worth pointing out with Witherington that when Jesus raised the dead, healed the deaf, blind, and lame, this is a sign that “Isaiah’s new creation is breaking into the midst of the old one, and that the road back from living in the land of disease, decay, and death, a sort of an exile form the land of life, the land oozing with milk and honey, is being paved by Jesus.” (p. 137)

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.

The links to books above above are paid links. Go with this one if you prefer: Isaiah Old and New: Exegesis, Intertexutality, and Hermeneutics.

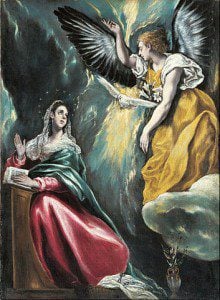

_-_Annunciation_-_Google_Art_Project-220x300.jpg)

I will finish out this Christmas season with a link to a recent issue of CBE’s Mutuality Magazine:

I will finish out this Christmas season with a link to a recent issue of CBE’s Mutuality Magazine:

The very idea that a virgin conceived and bore a son raises an eyebrow or two in our secular Western society – both modern and postmodern. At the risk of being a little too earthy – conception in humans requires input from two sources. After all, we all know that an egg from the woman requires the DNA from the sperm provided by a man to make it whole, capable of producing a new individual. One might, perhaps conceive of a clone of some sort using only Mary’s DNA – but this could only make a female, not a male. No Y Chromosome in Mary. If a virgin gave birth to a son it was a truly miraculous conception. The DNA had to come from somewhere. Did God just produce a a unique set of chromosomes to join with Mary’s? Was it Joseph’s DNA? Some other descendant of David? Was this a divine artificial insemination?

The very idea that a virgin conceived and bore a son raises an eyebrow or two in our secular Western society – both modern and postmodern. At the risk of being a little too earthy – conception in humans requires input from two sources. After all, we all know that an egg from the woman requires the DNA from the sperm provided by a man to make it whole, capable of producing a new individual. One might, perhaps conceive of a clone of some sort using only Mary’s DNA – but this could only make a female, not a male. No Y Chromosome in Mary. If a virgin gave birth to a son it was a truly miraculous conception. The DNA had to come from somewhere. Did God just produce a a unique set of chromosomes to join with Mary’s? Was it Joseph’s DNA? Some other descendant of David? Was this a divine artificial insemination? Interaction not Intervention. One of the most important criteria for thinking through the incredible claims in scripture is God’s interaction with his creatures rather than his intervention in his creation. The miracles ring true when they enhance our understanding of the interaction of God with his people in divine self-revelation. The virginal conception is part of the Incarnation, “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us”. The magnificent early Christian hymns quoted by Paul in Col 1.15-20 and Phil 2.6-11 catch the essence of this enacted myth as well.

Interaction not Intervention. One of the most important criteria for thinking through the incredible claims in scripture is God’s interaction with his creatures rather than his intervention in his creation. The miracles ring true when they enhance our understanding of the interaction of God with his people in divine self-revelation. The virginal conception is part of the Incarnation, “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us”. The magnificent early Christian hymns quoted by Paul in Col 1.15-20 and Phil 2.6-11 catch the essence of this enacted myth as well.

The relationship between God, humans, animals and land runs through the Old Testament, and especially the redemption of Israel from Egypt as related in Exodus to Deuteronomy. Ultimately God controls both abundance and lack, prosperity and want. As Moses told the people (Deut. 28):

The relationship between God, humans, animals and land runs through the Old Testament, and especially the redemption of Israel from Egypt as related in Exodus to Deuteronomy. Ultimately God controls both abundance and lack, prosperity and want. As Moses told the people (Deut. 28): Moo argues that sacrificial system itself is a testament to the connections and value of all life. The animals must have intrinsic value to serve as an atonement for human sin. Their lifeblood is to be treated with respect, buried and not consumed (a prohibition retained in the Gentile church Acts 15: 19-20,29)

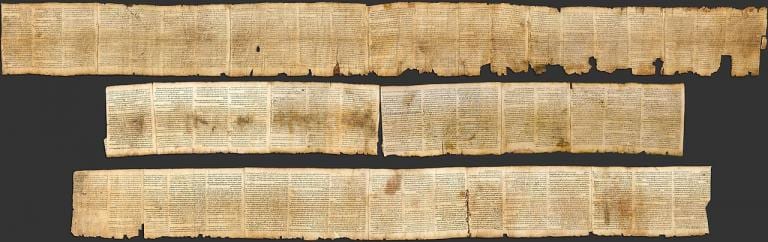

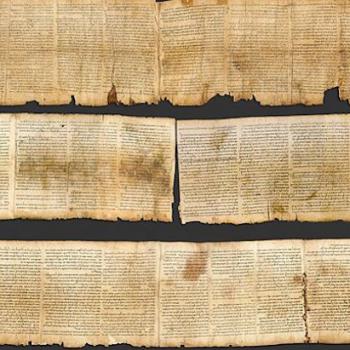

Moo argues that sacrificial system itself is a testament to the connections and value of all life. The animals must have intrinsic value to serve as an atonement for human sin. Their lifeblood is to be treated with respect, buried and not consumed (a prohibition retained in the Gentile church Acts 15: 19-20,29) Witherington also points out that while Jesus read Isaiah, the people didn’t. The book of Isaiah was of unparalleled importance in the early church, but it is important to remember that most of the population was illiterate or only functionally literate. (Literacy rates were probably around 15% – but are hard to quantify). Most of the population did not have access to scrolls or the ability, time, and desire to read and study them.

Witherington also points out that while Jesus read Isaiah, the people didn’t. The book of Isaiah was of unparalleled importance in the early church, but it is important to remember that most of the population was illiterate or only functionally literate. (Literacy rates were probably around 15% – but are hard to quantify). Most of the population did not have access to scrolls or the ability, time, and desire to read and study them.