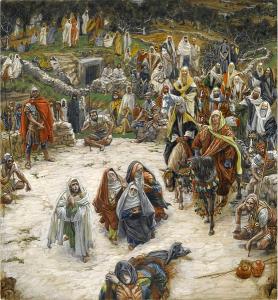

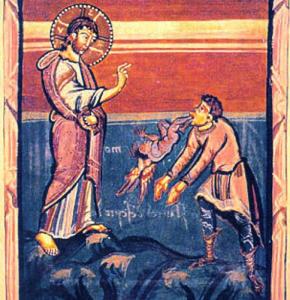

Jesus read Isaiah. Luke relates Jesus’ first recorded teaching moment, after his baptism and temptation.

Jesus returned to Galilee in the power of the Spirit, and news about him spread through the whole countryside. He was teaching in their synagogues, and everyone praised him.

He went to Nazareth, where he had been brought up, and on the Sabbath day he went into the synagogue, as was his custom. He stood up to read, and the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was handed to him. Unrolling it, he found the place where it is written:

“The Spirit of the Lord is on me,

because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners

and recovery of sight for the blind,

to set the oppressed free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

Then he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant and sat down. The eyes of everyone in the synagogue were fastened on him. He began by saying to them, “Today this scripture is fulfilled in your hearing.” (Luke 4:14-21)

Listening to – or reading – the Bible straight through, repeatedly and regularly, has many benefits. As I have continued the practice of listening on my morning commute – for almost a decade now – the dependence of the New Testament on the Hebrew Scriptures has become unmistakable, sometimes cropping up in the most unexpected places. What pops to mind when hearing Isaiah 22:21-22? “He will be a father to those who live in Jerusalem and to the people of Judah. I will place on his shoulder the key to the house of David; what he opens no one can shut, and what he shuts no one can open.“

Listening to – or reading – the Bible straight through, repeatedly and regularly, has many benefits. As I have continued the practice of listening on my morning commute – for almost a decade now – the dependence of the New Testament on the Hebrew Scriptures has become unmistakable, sometimes cropping up in the most unexpected places. What pops to mind when hearing Isaiah 22:21-22? “He will be a father to those who live in Jerusalem and to the people of Judah. I will place on his shoulder the key to the house of David; what he opens no one can shut, and what he shuts no one can open.“

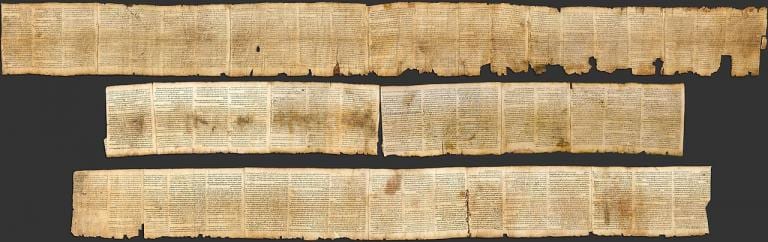

Echoes, allusions, and quotes from the Old Testament, permeate the New. The Psalms, prophets, especially Isaiah, lead the list. References to Isaiah average more than one a page. Ben Witherington III in his recent book Isaiah Old and New: Exegesis, Intertexutality, and Hermeneutics notes: “Almost everywhere one turns in the NT, one finds fingerprints of Isaiah. In some 300 pages of most any translation of the NT there are over 400 quotes, paraphrases, or allusions to Isaiah.” (p. 13) Even in this count, it is likely that we have missed some, the book was that important in the first century Jewish community and the early Christian church. Direct quotes are only the tip of the iceberg. For the Jew or Christian with a “Scripture-saturated way of thinking” paraphrases or allusions to Isaiah came automatically to mind. It is one of the best preserved books we have, with virtually the entire book in the Great Isaiah Scroll from Qumran (ca. 150 BC).

Jesus read Isaiah. Not as a proof text, but because the book was and is important. This alone should make the Isaiah worth careful consideration – both in its own context and in the way it is used by the Jesus, the Gospel writers in the letters of Paul, Peter, and James and in the book of Revelation. The NT use of Isaiah does not stand in a vacuum – with a new significance unattached to the original meaning of the book. Ben Witherington works through this in his book, “trying to understand its meaning in its original contexts first, before then asking and answering the question of how this same material is used by Jesus and the writers of the New Testament.” (p. 10)

We will join with Ben and consider the book of Isaiah and the echoes and allusions to the book in the New Testament.

What strikes you most about the book of Isaiah and the way it is used in the NT?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.

The link to the book above is a paid link. Go with this one if you prefer: Isaiah Old and New: Exegesis, Intertexutality, and Hermeneutics.

But who are his people? Are these the ones who heard and at one time said the right words? Is it it only those who have been baptized? Is it only those lucky enough to be “chosen,” born at the right time, in the right place, into circumstances making them receptive?

But who are his people? Are these the ones who heard and at one time said the right words? Is it it only those who have been baptized? Is it only those lucky enough to be “chosen,” born at the right time, in the right place, into circumstances making them receptive?

The true light gives sight to the blind. When Jesus spoke again to the people, he said, “I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness, but will have the light of life.” (8:12) And after restoring the man blind from birth: For judgment I have come into this world, so that the blind will see and those who see will become blind. (9:39)

The true light gives sight to the blind. When Jesus spoke again to the people, he said, “I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness, but will have the light of life.” (8:12) And after restoring the man blind from birth: For judgment I have come into this world, so that the blind will see and those who see will become blind. (9:39) But the greatest sign, Johnson argues, is the glorification of the Son. Incarnation ends in enthronement – but not before or without execution.

But the greatest sign, Johnson argues, is the glorification of the Son. Incarnation ends in enthronement – but not before or without execution.

So why are conservative Christians as a group (with many individual exceptions) anti-science when it comes to these kinds of issues: pollution control, environmental protection, climate change? It boggles my mind because there is no good theological reason for this attitude. In fact such virtues as stewardship and love for others dictates that we of all people should care. Not as radical green idealists who put the rest of nature over human flourishing, but as humans, God’s image, in the world to care for it and for others. Air pollution is a devastating problem in many cities around the world – as Southern Californians know quite well. Anthropogenic climate change is also a reality. How devastating might be up for debate – I don’t think this is an entirely settled question – but that doesn’t mean that we should sit back and do nothing, or worse yet, accelerate our pursuit of technologies suspected of making it worse.

So why are conservative Christians as a group (with many individual exceptions) anti-science when it comes to these kinds of issues: pollution control, environmental protection, climate change? It boggles my mind because there is no good theological reason for this attitude. In fact such virtues as stewardship and love for others dictates that we of all people should care. Not as radical green idealists who put the rest of nature over human flourishing, but as humans, God’s image, in the world to care for it and for others. Air pollution is a devastating problem in many cities around the world – as Southern Californians know quite well. Anthropogenic climate change is also a reality. How devastating might be up for debate – I don’t think this is an entirely settled question – but that doesn’t mean that we should sit back and do nothing, or worse yet, accelerate our pursuit of technologies suspected of making it worse. Katherine Hayhoe, an evangelical Christian, a climate scientist, and a voice advocating for careful consideration of the issues in the evangelical church (she isn’t willing to give up the term even though it has been tarnished by some of us) has an

Katherine Hayhoe, an evangelical Christian, a climate scientist, and a voice advocating for careful consideration of the issues in the evangelical church (she isn’t willing to give up the term even though it has been tarnished by some of us) has an

The healing miracles (including the restoration of the Synagogue leaders daughter to life) physical ailments are at the root of the problem. In both the exorcisms and the healings, human beings are restored to normal society and human companionship. Here, however, the emphasis isn’t of cosmic powers and spiritual domination, but on the pain and suffering and distress of the people. Jesus makes people whole, a clear harbinger of the coming Kingdom. It is also significant that Jesus shows concern, compassion, and mercy for the people he encounters. He brings sight to the blind and hearing to the deaf in more ways than one.

The healing miracles (including the restoration of the Synagogue leaders daughter to life) physical ailments are at the root of the problem. In both the exorcisms and the healings, human beings are restored to normal society and human companionship. Here, however, the emphasis isn’t of cosmic powers and spiritual domination, but on the pain and suffering and distress of the people. Jesus makes people whole, a clear harbinger of the coming Kingdom. It is also significant that Jesus shows concern, compassion, and mercy for the people he encounters. He brings sight to the blind and hearing to the deaf in more ways than one.