By Chris Seidman. Since 2001, Chris has served as lead minister of The Branch Church, a multi-site church in Dallas with more than 100 years of rich history. Chris is privileged to preach occasionally in churches, on college campuses, and in conferences across the country and often has his golf clubs in tow. He is also distinguished as an author who has written more books than he has sold. So he has that going for him.

By Chris Seidman. Since 2001, Chris has served as lead minister of The Branch Church, a multi-site church in Dallas with more than 100 years of rich history. Chris is privileged to preach occasionally in churches, on college campuses, and in conferences across the country and often has his golf clubs in tow. He is also distinguished as an author who has written more books than he has sold. So he has that going for him.

Sooner or later ministry has a way of smoking out our insecurities. The painful reality is the insecurities of servant leaders can complicate already complex situations in the life of a church, or organization, or family. One of the greatest gifts I can give the people I’m serving is to live from the blessing of God instead of for the blessing of others. I unpacked this idea with you in my previous post. (You can read it here http://www.patheos.com/blogs/jesuscreed/2018/01/10/ministry-not-blessing/)

It was at the ripe-old age of 30, that I began serving as lead minister of the church where I still am today. That was 17 years ago this month. When I began, every member of our staff was older than me. There aren’t words to convey my appreciation for their humility and patience with me in those early years and for our present staff’s humility and patience with me.

The Deep End

Since then, I’ve been in the deep end, way over my head. Here a few highlights that are not really all that unusual for a lot of us who’ve serve in churches.

There was the challenge of helping a 105 year-old church evolve from a traditional paradigm of worship to a more contemporary approach (and I know those terms “traditional” and “contemporary” can have varying definitions). And then there was the challenge of navigating those waters without blowing too big of a hole in the boat.

There was the challenge of transitioning from a church in one location into a multi-site church.

There was the time when we laid off several staff members at once due to a financial crunch shortly after expanding to two campuses.

There were challenges related to moral failures of fellow ministers.

There were challenges associated with changing the name of our church which had gone by the same name for more than a century.

There were challenges associated with our church becoming more diverse racially and socio-economically.

There were challenges that came with an evolution of our understanding of the work of the Spirit.

(By the way, in no way have we “arrived.” We still have our challenges!)

These short sentences I’ve just written can in no way sum up the kind of ambivalence, uncertainty, and varying levels of heartache wrapped up in each situation. My heart is still quite tender with many memories associated with these experiences. I made many mistakes and have learned some hard lessons.

And then there’s the reality of my own fallen nature being in the mix. As Eugene Peterson puts it, “Every congregation is a congregation of sinners. As if that weren’t bad enough, they all have sinners for pastors!” God and the church where I serve have been exceedingly gracious to me.

A Helpful Prayer

The longer I’m in ministry the more I’ve come to appreciate Paul’s prayer over a church that was facing challenges of its own. “And this is my prayer that you love may abound more and more in knowledge and depth of insight, so that you may be able to discern what is right….” (Philippians 1:9)

It isn’t always easy to know in times of challenge or transition what the most loving thing to do is. It’s why we need this prayer in our lives. So often I’ve found myself in a fog along with others trying to discern the right thing to do in times of challenge and transition as a church.

The Snare Of Living For A Blessing From Others

One of the things I’ve learned in those times is how thick the fog gets when my sense of identity and security is not firmly rooted in what God has proclaimed over me and demonstrated for me in Christ. I confessed you in my last post about my propensity to be consumed with what others may think or say about me. Few things pollute the process of discerning what the right thing to do is in a given situation, like a preoccupation with what others will say or think about you if you do “this” or “that.”

As the writer of Proverbs noted, the fear of others will prove to be a snare (Proverbs 29:25). It can be ensnaring in so many ways – one of which is the difficulty it adds to the process of discerning the right thing to do in a given situation.

This is where learning to live from the blessing of God instead of for the blessing of others can make such an important impact. When our security is not in what God has proclaimed over us and demonstrated for us in Jesus, it all too easily gravitates toward what others say to us or about us. This isn’t just true in my particular vocation. This can infect most any arena of life. More than once I’ve heard exasperated parents who don’t know what to do with a child say, “What will people say (or think) about us?”

Without realizing it, we can make whatever challenge, drama, or transition we were in as a church, family, or organization about ourselves in my own mind. How quickly we can turn our sacred communities and callings into “personal proving grounds” where our primary objective is to prove something about ourselves to ourselves or to others.

So much is hijacked in a community of faith when its servant leaders are ensnared with a preoccupation of what others may be thinking or saying about them. Sometimes the “others” aren’t in the church. They’re in the past. Or they’re in another city. Or they’re online. (Of course, people don’t think about us near as much as we’d like to think. But that fact does little to prevent some of us from being consumed with the possibility.)

Living From The Blessing Of God And The Dissipating Fog

I’ve found, though, that when my sense of identity and security is in the right place, I’m liberated from a preoccupation with what others think of me or how they’ll respond. The fog in difficult times of discernment begins to dissipate. I’m enabled to be completely given over to the integrity of the process of discerning, along with other servant-leaders, what God is calling us to do. It becomes possible for us to, as Charles Stanley put it, “Obey God and leave the consequences to him.”

If you smell the smoke of your own insecurities – or others do who you trust – own it and take heart. It is God’s will to set us free from a paralyzing preoccupation with ourselves. His mercies are new every morning (Lamentations 3:22-23). And speaking of morning, take C.S. Lewis’ advice to heart.

“It comes the very moment you wake up each morning. All your wishes and hopes for the day rush at you like wild animals. And the first job each morning consists simply in shoving them all back; in listening to that other voice, taking that other point of view, letting that other larger, stronger, quieter life come flowing in. And so on, all day….”

This “larger, stronger, quieter life” to me is the ministry of the Holy Spirit who reminds us of who we are as sons and daughters of the Father (Romans 8:16). We’d be wise to wake up to this “larger, stronger, quieter life” before we wake up to our devices and screens, or people’s opinions and fears.

The more we live from the blessing of God, the better position we are in to discern the right thing to do and be a true blessing to others.

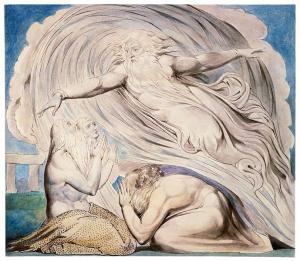

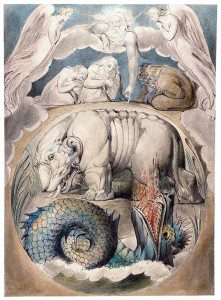

The message of Job, however, is not found in the speeches of Job or any of his friends. The message is found when God appears on the scene and addresses Job from the whirlwind. This isn’t a putdown squashing Job’s questions under God’s majesty. Rather McLeish views it as an acknowledgment of the significance of Job’s questions and his right to pose them, “for the invitation to ‘gird up your loins’ is spoken, shockingly, to a legal adversary of equal standing, not an inferior.” (p. 141) The walk through creation, including the questions posed to Job, for example:

The message of Job, however, is not found in the speeches of Job or any of his friends. The message is found when God appears on the scene and addresses Job from the whirlwind. This isn’t a putdown squashing Job’s questions under God’s majesty. Rather McLeish views it as an acknowledgment of the significance of Job’s questions and his right to pose them, “for the invitation to ‘gird up your loins’ is spoken, shockingly, to a legal adversary of equal standing, not an inferior.” (p. 141) The walk through creation, including the questions posed to Job, for example: Rather than bypassing Job’s questions and squashing them with is majesty, the Lord is answering Job’s questions – or more accurately guiding him to the answers for the questions he should have been asking in the first place. McLeish sees five lines of argument for this view. (p. 146-148)

Rather than bypassing Job’s questions and squashing them with is majesty, the Lord is answering Job’s questions – or more accurately guiding him to the answers for the questions he should have been asking in the first place. McLeish sees five lines of argument for this view. (p. 146-148)

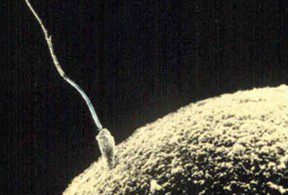

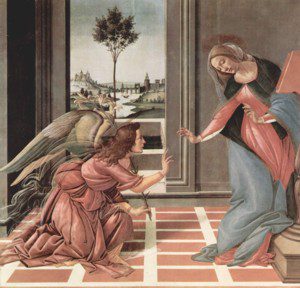

The very idea that a virgin conceived and bore a son raises an eyebrow or two in our secular Western society – both modern and postmodern. At the risk of being a little too earthy – conception in humans requires input from two sources. After all, we all know that an egg from the woman requires the DNA from the sperm provided by a man to make it whole, capable of producing a new individual. One might, perhaps conceive of a clone of some sort using only Mary’s DNA – but this could only make a female, not a male. No Y Chromosome in Mary. If a virgin gave birth to a son it was a truly miraculous conception. The DNA had to come from somewhere. Did God just produce a a unique set of chromosomes to join with Mary’s? Was it Joseph’s DNA? Some other descendant of David? Was this a divine artificial insemination?

The very idea that a virgin conceived and bore a son raises an eyebrow or two in our secular Western society – both modern and postmodern. At the risk of being a little too earthy – conception in humans requires input from two sources. After all, we all know that an egg from the woman requires the DNA from the sperm provided by a man to make it whole, capable of producing a new individual. One might, perhaps conceive of a clone of some sort using only Mary’s DNA – but this could only make a female, not a male. No Y Chromosome in Mary. If a virgin gave birth to a son it was a truly miraculous conception. The DNA had to come from somewhere. Did God just produce a a unique set of chromosomes to join with Mary’s? Was it Joseph’s DNA? Some other descendant of David? Was this a divine artificial insemination? Interaction not Intervention. One of the most important criteria for thinking through the incredible claims in scripture is God’s interaction with his creatures rather than his intervention in his creation. The miracles ring true when they enhance our understanding of the interaction of God with his people in divine self-revelation. The virginal conception is part of the Incarnation, “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us”. The magnificent early Christian hymns quoted by Paul in Col 1.15-20 and Phil 2.6-11 catch the essence of this enacted myth as well.

Interaction not Intervention. One of the most important criteria for thinking through the incredible claims in scripture is God’s interaction with his creatures rather than his intervention in his creation. The miracles ring true when they enhance our understanding of the interaction of God with his people in divine self-revelation. The virginal conception is part of the Incarnation, “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us”. The magnificent early Christian hymns quoted by Paul in Col 1.15-20 and Phil 2.6-11 catch the essence of this enacted myth as well.