For some religions are all doing the same basic things. Varieties and differences notwithstanding, Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism — or jumping back in time — Roman religions and gods and worship and Judaism as well as its mutation, Christianity, are all doing the same. This is how religion scholarship addresses world religions and it is how such historians see the 1st Century.

For some religions are all doing the same basic things. Varieties and differences notwithstanding, Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism — or jumping back in time — Roman religions and gods and worship and Judaism as well as its mutation, Christianity, are all doing the same. This is how religion scholarship addresses world religions and it is how such historians see the 1st Century.

But comparison of religions to find similarities only approximates accuracy; one must also note their differences, differences held in more than high regard by the proponents of the various religions. (The term “religion” of course has a history and a nuance that modern separation of the religious world from the secular world often trumpets.)

Furthermore, there is an emphasis today among scholars of both Judaism and Christianity to emphasize commonalities between the two — is this accurate? We turn to a new and very important study.

This approach is why Larry Hurtado, A Destroyer of the Gods: Early Christian Distinctiveness in the Roman World, is so important. Hurtado thinks, with more than a tipping of the hat to how the term religion is understood, Christianity was a mutation of Judaism but was in many senses a new kind of religion.

I begin with his careful description of the religions of the Roman world, and he notes a kind of tolerance and respect and pluralism, even polytheism, at work in that world — and it is the world out of and into which Judaism and Christianity emerge and speak. Notice this kind of blending of the gods into a homogenous kind of piety (it’s on full display in the Roman novel called Ephesiaca):

Each of the many peoples of the Roman Empire had their own traditional, and multiple, deities, and in that period the tendency was to recognize and welcome them all. In general, the attitude toward this rich diversity of gods was “completely tolerant, in heaven as on earth. 45

To deny a deity worship, and that typically meant sacrifice, was, effectively, to deny the god’s reality. Individual pagans of that time did not feel it obligatory to reverence each and every deity, but, in principle, all gods were entitled to be reverenced. So, the people of the Roman period generally found no problem in participating in the worship of various and multiple deities. 47

Indeed, for people in the Roman era generally, ‘piety” meant a readiness to show appropriate reverence for the gods, any and all the gods. 48

But both Judaism and Christianity cut against the grain and scraped the chalkboard, and here is the general perception:

Outright refusal to worship deities was deemed bizarre, even antisocial, and, worse still, impious and irreligious. 48

Hurtado goes to pains to emphasize the distinctiveness of the Christian faith on this matter and where their challenge and courage arose:

This is particularly where the religious beliefs and stance of early Christianity stand out as different. Christians were expected to avoid taking part in the worship of any deity other than the one God of the biblical tradition. … Given the ubiquitous place of the gods and their rituals in Roman-era life, however, it would have been difficult for Christians simply to avoid all such rituals without being noticed. Christians likely often also had to refuse to join in the worship of the various divinities and so had to negotiate their relationships carefully, especially, no doubt, those involving family and close acquaintances. 49

In short, precisely that which was generally considered piety (religio or eusebeia), reverencing the many gods, was, for early Christians, idolatry, impiety of the gravest sort. 50

For some reason, Hurtado shows, Judaism was more or less tolerated when it came to their refusals and denials, and he contends it was because they had a national religion of one God:

The difference and distinguishing feature of the early Christian stance against “idolatry” is this: In the eyes of ancient pagans, the Jews’ refusal to worship any deity but their own, though often deemed bizarre and objectionable, was basically regarded as one, rather distinctive, example of national peculiarities. … But, in general, however strange they seemed, the national peculiarities of various peoples were taken in stride, Jewish peculiarities included. Every people had its peculiarities, and, on the matter of the worship of the gods, so did the Jews, only more so! 52-53

But Christianity was distinct and courageous and it became more challenging because it was not a national religion and the denials were pervasive and required. This makes Christianity undoubtedly different and distinct:

This total withdrawal from the worship of the many deities was a move without precedent, and it would have seemed inexplicable and deeply worrying to many of the general populace. 54

So, to refuse to worship these deities could be taken as a deeply subversive action or at least a disregard for the political order.54

Indeed, the exclusivist stance of early Christianity was so odd, unjustified, and even impious in the eyes of ancient pagan observers and critics that they often accused Christians of being atheists, just as Jews had been labeled previously! 56

In my next post, I will sketch the Christian view of God that made Christianity’s faith so distinctive.

The story of Jacob’s time in Paddan-Aram, serving his uncle, acquiring two wives, 11 sons, a daughter, and much livestock is well known. God is at work, although the family is far from perfect – or faithful. When Jacob leaves to return home after an absence of 20+ years his wife Rachel steals the household gods to bring with her. En route and wary of the reception he can expect from his brother, Jacob again meets God it seems. (Image by

The story of Jacob’s time in Paddan-Aram, serving his uncle, acquiring two wives, 11 sons, a daughter, and much livestock is well known. God is at work, although the family is far from perfect – or faithful. When Jacob leaves to return home after an absence of 20+ years his wife Rachel steals the household gods to bring with her. En route and wary of the reception he can expect from his brother, Jacob again meets God it seems. (Image by

For many people in the 21st century the search for some transcendent meaning is futile, a mere chasing after rainbows. The meaning of life is simply what you make of it – relationships, pleasure, achievement, accomplishment (which can include sacrificial service) – in the limited time available. Certainly this has been the response of many commenters when I’ve delved into the questions of purpose and meaning in the past. In ch. 3 of his new book

For many people in the 21st century the search for some transcendent meaning is futile, a mere chasing after rainbows. The meaning of life is simply what you make of it – relationships, pleasure, achievement, accomplishment (which can include sacrificial service) – in the limited time available. Certainly this has been the response of many commenters when I’ve delved into the questions of purpose and meaning in the past. In ch. 3 of his new book  Keller argues that discovered meanings are more rational (and more satisfying) than created meanings. Ultimately created meanings are temporary. It simply doesn’t really “matter whether you are a genocidal maniac or an altruist; it won’t matter whether you fight hunger in Africa or are incredibly cruel and greedy and starving the poor.” (p. 66) We all die eventually, it is likely that mankind as a species will die out naturally, and virtually guaranteed that our solar system will eventually vanish one way or another. (Solar image from NASA)

Keller argues that discovered meanings are more rational (and more satisfying) than created meanings. Ultimately created meanings are temporary. It simply doesn’t really “matter whether you are a genocidal maniac or an altruist; it won’t matter whether you fight hunger in Africa or are incredibly cruel and greedy and starving the poor.” (p. 66) We all die eventually, it is likely that mankind as a species will die out naturally, and virtually guaranteed that our solar system will eventually vanish one way or another. (Solar image from NASA)

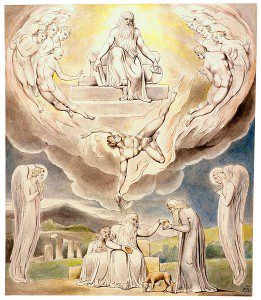

The book of Job is a work of theological literature. Both Longman and Walton see it as a sophisticated and carefully constructed work. The book consists of a prologue and opening lament (ch. 1-3), a cycle of dialogue between Job and his three friends (ch. 4-27), a wisdom hymn (28), a discourse by Job (ch. 29-31), a discourse by Elihu (ch. 32-37), a discourse by God (ch. 38-41) and an closing and epilogue (ch. 42). (The drawings are by William Blake – available

The book of Job is a work of theological literature. Both Longman and Walton see it as a sophisticated and carefully constructed work. The book consists of a prologue and opening lament (ch. 1-3), a cycle of dialogue between Job and his three friends (ch. 4-27), a wisdom hymn (28), a discourse by Job (ch. 29-31), a discourse by Elihu (ch. 32-37), a discourse by God (ch. 38-41) and an closing and epilogue (ch. 42). (The drawings are by William Blake – available