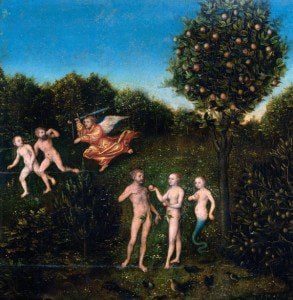

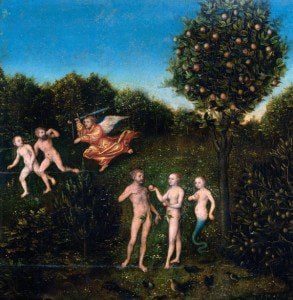

Chapter 7 of Mark Harris’s book The Nature of Creation: Examining the Bible and Science turns to the question of the Fall. In many ways this is the key question when examining the Bible and Science. Some things simply seem inexplicable in the context of a “good” creation, the product of an all powerful, all knowing, loving God. One of these critters in our backyard doesn’t belong. Skunks aren’t exactly evil – but it seems a stretch to call them good (at least in the backyard). The rabbit was quite wary – essentially a statue until the skunk wandered away.

Chapter 7 of Mark Harris’s book The Nature of Creation: Examining the Bible and Science turns to the question of the Fall. In many ways this is the key question when examining the Bible and Science. Some things simply seem inexplicable in the context of a “good” creation, the product of an all powerful, all knowing, loving God. One of these critters in our backyard doesn’t belong. Skunks aren’t exactly evil – but it seems a stretch to call them good (at least in the backyard). The rabbit was quite wary – essentially a statue until the skunk wandered away.

Of course the presence of skunks in the backyard, or even the existence of scorpions, venomous snakes, and parasites, is not really the point. There are theological issues that raise the biggest questions. Harris suggests that two theological problems are seen to arise in the absence of The Fall.

First there is the problem of evil. Darwinism implies that competition, struggle, suffering and death have always been integral to the world. Theologically, they must therefore arise from God’s initial creative act (and continuing creative actions); they are “necessary evils”, part of what has made the world what it is. The same might even be said of human sin, since it can be construed as inherent to the original created order if it is seen as the inevitable outcome of the selfishness which arises from the struggle for existence implanted in the evolutionary process. (p. 131)

Many will take this to indicate that evolutionary creation makes God the source of sin and evil in the world and reject evolution on these grounds. Others resolve the conundrum other ways. A good God cannot be the source of evil, thus it becomes important to retain the notion of humanity as fallen, detoured as a race from God’s ideal plan. The question for many becomes “can we have fallenness without The Fall?”

The second theological problem raised by Darwinism concerns Christ;

The resurrection of Jesus Christ makes Neo-Darwinism incompatible with Christianity. Accommodating Neo-Darwinism leaves the biblical story, centred on the resurrection, incoherent, as it creates a story in which the hero Jesus, through his resurrection defeats an enemy (1 Cor. 15:26) of his own making. (Lloyd 2009: 1 in Debating Darwin)

There you have it in a nutshell, the concern shared by many conservative Christians about Darwinism: that it is incompatible with Christian faith because Darwinism appears to make Christ’s achievement pointless. (p. 132-133)

Both of these problems are related – and both have the same core concern. We need, so it is claimed, fallenness and a Fall to have a coherent story of redemption. And, without a historical Adam, the Fall, and thus Christianity, is vanquished to the dustbin of failed hypotheses.

Harris looks at several aspects of this claim.

A Historical Adam. Harris runs through several of the solutions that have been proposed to retain a historical Adam and The Fall despite the evidence for evolution and common descent. Some will suggest that there was a bottleneck, perhaps even a pair, in human population – a solution that is not consistent with the evidence as Dennis Venema has argued in a series of posts at BioLogos (Adam, Eve, and Population Genetics). Denis Alexander argues for a Neolithic Adam, different from his forebears and contemporaries as Homo divinus – there is a theological distinction between Adam and the others making Adam and Eve the first spiritual humans (BioLogos blog series Genetics, Theology, and Adam as a Historical Person and also his book Creation or Evolution: Do We Have to Choose?). John Walton’s approach is somewhat different – but as his new book appeared more recently it isn’t included in Harris’s chapter. These solutions can seem strained. Their coherence and plausibility rests on the importance that a person attaches to the theological significance of the Fall and to their view of the nature of Scripture as authoritative.

Does Genesis Teach that Sin and Death are Coupled? Harris argues that the answer is no (as do Walton and many others) if by this we mean that intrinsic immortality was lost through sin. Although God warns the man concerning the tree of the knowledge of good and evil “for in the day that you eat from it you will surely die,” neither the man nor the woman die for many hundreds of years. The NIV cognizant of this fact softens the translation: “for when you eat from it you will certainly die,” and David Stern in The Complete Jewish Bible translates it “because on the day that you eat from it, it will become certain that you will die.” But the Hebrew has “in the day.” Here’s the problem:

Does Genesis Teach that Sin and Death are Coupled? Harris argues that the answer is no (as do Walton and many others) if by this we mean that intrinsic immortality was lost through sin. Although God warns the man concerning the tree of the knowledge of good and evil “for in the day that you eat from it you will surely die,” neither the man nor the woman die for many hundreds of years. The NIV cognizant of this fact softens the translation: “for when you eat from it you will certainly die,” and David Stern in The Complete Jewish Bible translates it “because on the day that you eat from it, it will become certain that you will die.” But the Hebrew has “in the day.” Here’s the problem:

God appears to threaten the man and the woman with what turns out to be an untruth, while the serpent leads them into enlightenment by telling them the truth. That this was a theological problem was recognized early on, since we find ingenious attempts to resolve it even in the inter-testamental period (e.g. Jubilees 4:29-30; see Kugel 1997: 68-69). (p. 137)

This ingenious attempt is one that many have followed – Adam died at 930, 70 years shy of 1000 “for one thousand years are as one day in the testimony of the heavens” according to the author of Jubilees.

Although Adam and Eve did not immediately die, Harris points out that they were punished for their action and this punishment leads to death.

(1) God curses the ground so that the man must work hard to grow crops for food; (2) God increases the woman’s pain in childbirth; (3) God expels them from the garden. … But it is the third punishment which has the most bearing on the question of death. The rationale behind the expulsion from the garden seems to be that, if the man and the woman remain, they will be able to eat from the tree of life which is in the garden, and “live forever” (Gen 3:22). (p. 137)

The last is the significant point. There is no indication in the text that the man and woman were initially immortal, but without access to the tree of life they would surely die.

There is a tradition in the last few centuries B.C.E. found in extra canonical texts that Adam and Eve were initially immortal and were made mortal. Harris references Wisdom 1:13, 2:23-24, Sirach 25:24, and 1 Enoch 69:11 as examples. But this tradition expands on Genesis, it is not an accurate textual reading of Genesis.

Genesis 3 in the context of Genesis 2-11. In Genesis 4-11 we find a series of stories involving subsequent acts of disobedience and the consequences of these actions. As in Genesis 3 there are real consequences – but also the story of a God who doesn’t give up on his people. Key points:

In every case humankind is seen to overstep the mark, and God responds, as in the garden, by re-asserting divine domination and by underscoring the limits of humankind. (p. 138)

We see that humankind is punished consistently for every act of disobedience, but only ever in passing. God may threaten, but God never abandons humankind altogether: in various concrete ways God still protects, cares for, and blesses them. (p. 138-139)

Humankind is stricken by guilt and death throughout, by the inevitable finitude of existence, but simultaneously enjoys freedom and God’s blessing. (p. 139)

Although Christian theology has tended to see this all as the consequence of a single decisive Fall, this isn’t the only, or even the best, reading of the text.

Moving on to Paul and Adam. Harris has more discussion of this than I can do justice to in a short post. In conclusion he notes that …

Paul does not appear to believe in “original sin” transmitted down the generations from Adam. His point appears to be that all humans sin in the same way as Adam, and that therefore all die in the same way as Adam. This may stem from a rather loose reading of J, but it is not clear that Paul is offering us a reading of it as such. Rather, Paul is using Adam in a loose figurative way: Adam is the representative symbol of all that Christ redeemed and reversed, in every generation of humans. (p. 141)

The point of Paul’s argument is not Adam, but Christ. Paul sees Adam as the original sinner, but all sin and each succeeding generation has “shared fully and without exception in sin by means of their own deeds.” Key point: “Paul is seeking to draw out the significance of Christ as a universal, not to historicize Adam as a particular. (p. 142)

A historical Fall preserves God’s goodness. That humans are fallen is an indisputable fact, attested to in both the Old and New Testaments and in human experience. But what does this mean for The Fall? Must there be a definitive once and for all Fall? The fall of humankind, like the supernatural fall of angels attested to in extra-canonical sources and referenced in Jude and Revelation, serves the purpose to preserve God’s goodness. “The historical Fall means that God is not the source of historical evil, and the fall of the angels means that God is not the source of supernatural evil either.” (p. 143)

Harris links this to the importance of human (and angelic) free will. “The importance of the Fall lies in its connecting human free will with the historical beginnings of suffering, evil, and death, which is why Romans 5 is so significant, not least because if offers the possibility of redemption. (p. 146) Only with free will, God given of course, is God not the source of evil in the world.

There is far more to be said here – and Harris will dig deeper in the next chapter on suffering and evil.

What are the primary conflicts between human evolution and Christian theology?

Do the two theological problems at the top of this post concern you?

Are there other problems as well that we should consider?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.

From a website titled “Spark Notes” about Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, I learned the following: “In order to suggest the profundity of the old man’s sacrifice and the glory that derives from it, Hemingway purposefully likens Santiago to Christ, who, according to Christian theology, gave his life for the greater glory of humankind. Crucifixion imagery is the most noticeable way in which Hemingway creates the symbolic parallel between Santiago and Christ. When Santiago’s palms are first cut by his fishing line, the reader cannot help but think of Christ suffering his stigmata. Later, when the sharks arrive, Hemingway portrays the old man as a crucified martyr, saying that he makes a noise similar to that of a man having nails driven through his hands. Furthermore, the image of the old man struggling up the hill with his mast across his shoulders recalls Christ’s march toward Calvary. Even the position in which Santiago collapses on his bed—face down with his arms out straight and the palms of his hands up—brings to mind the image of Christ suffering on the cross. Hemingway employs these images in the final pages of the novella in order to link Santiago to Christ, who exemplified transcendence by turning loss into gain, defeat into triumph, and even death into renewed life.”

From a website titled “Spark Notes” about Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, I learned the following: “In order to suggest the profundity of the old man’s sacrifice and the glory that derives from it, Hemingway purposefully likens Santiago to Christ, who, according to Christian theology, gave his life for the greater glory of humankind. Crucifixion imagery is the most noticeable way in which Hemingway creates the symbolic parallel between Santiago and Christ. When Santiago’s palms are first cut by his fishing line, the reader cannot help but think of Christ suffering his stigmata. Later, when the sharks arrive, Hemingway portrays the old man as a crucified martyr, saying that he makes a noise similar to that of a man having nails driven through his hands. Furthermore, the image of the old man struggling up the hill with his mast across his shoulders recalls Christ’s march toward Calvary. Even the position in which Santiago collapses on his bed—face down with his arms out straight and the palms of his hands up—brings to mind the image of Christ suffering on the cross. Hemingway employs these images in the final pages of the novella in order to link Santiago to Christ, who exemplified transcendence by turning loss into gain, defeat into triumph, and even death into renewed life.”