It may sound like a stretch, but you can learn a lot about contemporary faith and politics from colonial needlework.

American colonists struggled to make sense of the events leading up to the war with Britain. Escalating encroachments were resisted by the colonists, whose sometimes-violent actions provoked further crackdowns. The cycle intensified throughout the late 1760s and into the new decade, spawning boycotts, riots, and worse, including the Boston Massacre in March 1770.

If historians today have a hard time explaining those events with all the necessary nuance and care, despite the benefits of time, perspective, and access to reams of relevant facts and details, then imagine the impossibility of doing so in the thick of things, when presumption and fear and recrimination spread faster than truth or prudence could manage.

In this challenging time, colonists sought clarity through the lens of faith. As largely Christian people, they framed their struggles in terms of their religion, looking to the Bible for patterns, types, and stories that could explain their predicament.

To see this in action, you need only look at a woman’s needlework.

A stitch in time

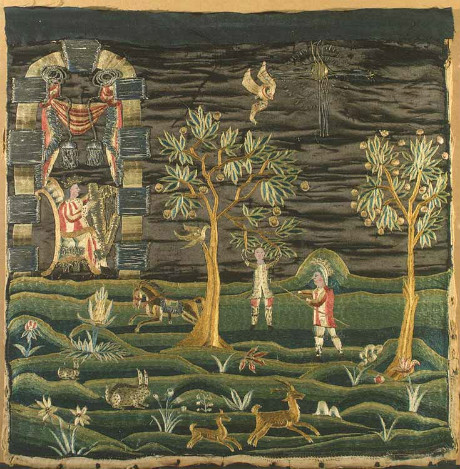

Following the Boston Massacre, Faith Trumbull, wife of patriotic Connecticut Governor Jonathan Trumbull and mother of famed portraitist John Trumbull, stitched an elaborate scene to explain the shocking event.

The embroidery depicted the death of Absalom. As the story goes, King David of Israel is met with an insurrection led by his son, Absalom, who is killed by David’s rogue commander, Joab. In the needlework, Joab is wearing a red coat. The point was clear enough: The grievance may be legitimate — King David/George is depicted as aloof and playing a harp — but care is needed; rebellion may end up backfiring. How to communicate a deeply important truth about breaking events? With Bible stories, of course.

And it wasn’t just needlework. When Paul Revere wanted to explain the colonists’ cause, he reached for a biblical allusion as well — telling his British cousin that England wanted to make the Americans “hewers of wood and drawers of water,” a reference to the ninth chapter of Joshua.

Open the index of a collection like American Political Writing During the Founding Era, edited by Charles S. Hyneman and Donald S. Lutz. “God” is referenced well over a hundred times, “Jesus” at least half as many times. Biblical figures and books like “Job,” “Isaiah,” “Ezra,” and “Judah” are all mentioned. “Peter” and “Paul” both score more than a dozen references apiece. And this is just one isolated sample; others abound.

Genuine belief

Scholars may say that the Revolutionary generation appealed to religion because they could justify their rebellion in terms of it, that they could find firm moral, even theological, footing while overthrowing the government. No doubt, that was certainly an outcome. But I think the more basic reason is that they simply believed it. They read, heard, prayed, and contemplated the words of the Bible. They identified with its stories and doctrines.

Trumbull stitched the scene with Absalom because she was familiar with the story — directly or indirectly — and found application with it. Revere went back to Joshua because he knew it. Ditto for the pamphleteers, orators, newspaper writers, and others of the time.

They brought the Bible to bear on the moment because they believed it, because it was part of their cultural inheritance, and because they found it relevant and applicable. It was the same during the Civil War, the Progressive Era, and the Civil Rights Movement.

It’s the same today.

A more generous read

When Tea Partiers on the right or social-justice advocates on the left make shows of their faith and wax biblical about policies, the natural impulse of many seems to be to dismiss it as hypocritical or manipulative, somehow self-serving or false, and maybe — if you’re really cynical — all of the above.

Putting disagreements with the particular policies aside, a more generous and thoughtful read of the picture might lead observers to realize that these people bring the Bible to bear on the moment because they believe it, because it is part of their cultural inheritance, and because they find it relevant and applicable.

Given our long history — one in which every generation, from the Pilgrims to Palin, has characterized their times and struggles in such terms — it shouldn’t be so difficult to accept.

A slightly altered version of this article was published November 19, 2010, under the title “Tea, Politics, and Faith” at FoxNews.com.