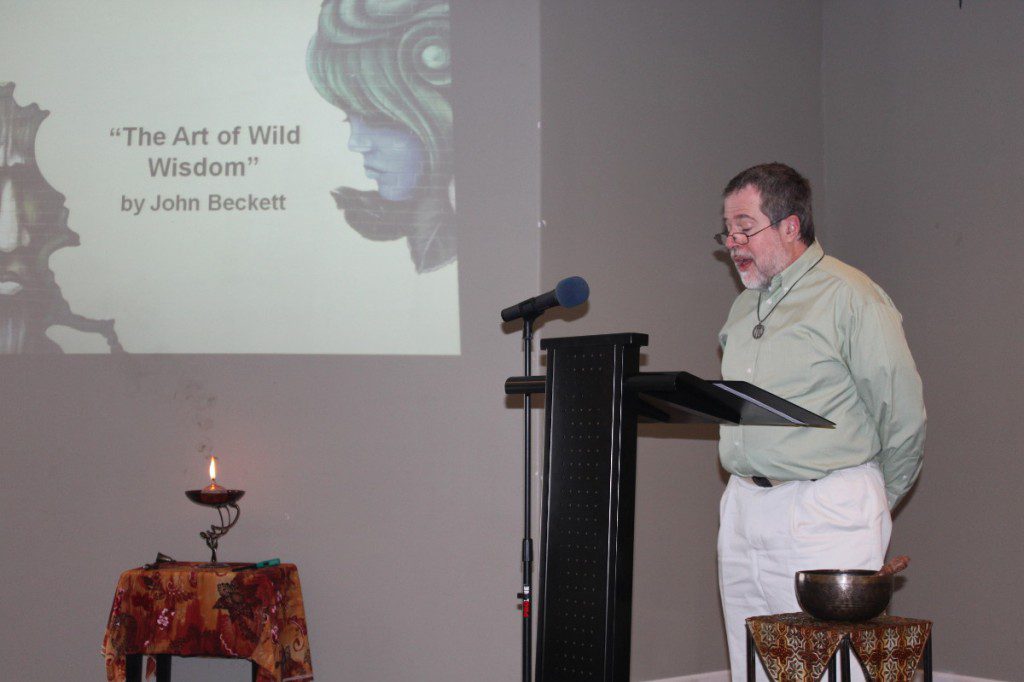

by John Beckett

Pathways UU Church

November 17, 2013

The Ancient Druids

“The Druids may well have been the most prominent magico-religious specialists of some of the peoples of north-western Europe just over a couple of thousand years ago; and that is all we can say of them with reasonable certainty.”

This is the opening line of Blood and Mistletoe: the History of the Druids in Britain by Ronald Hutton, Professor of History at the University of Bristol in England. It describes the difficulty of studying the ancient Druids: there are very few written accounts of who they were and what they did. Hutton says “the total number of [these sources] can be encompassed within a dozen pages of relatively large print.” Some of the sources likely reported hearsay as observed fact, and some of them (like Julius Caesar) clearly had a political motive to portray the Druids in a negative light.

But there are things we can say about the ancient Druids with confidence. They were part of the Celtic communities that covered much of Europe three thousand years ago. By the time written history caught up with them, they were primarily limited to Britain, Ireland and Gaul. The Druids were the priests, judges, healers, and keepers of records and lore. They were not kings, but they were advisors to kings.

It took many years of study to become a Druid – some sources say 19 years. They were not illiterate, but they kept an oral tradition, presumably to keep sacred lore from being profaned. Philip Carr-Gomm, who is Chosen Chief of the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids said they kept an oral tradition because they hadn’t invented these [eyeglasses].

They did not build Stonehenge or any of the other megalithic monuments. Those had been built, rebuilt and abandoned long before the Celts appeared in Britain.

As priests, they presided over sacrifices and took omens through various forms of augury. Whether those sacrifices included humans is uncertain. The charge of human sacrifice was levied by the invading Romans eager to portray the Celts as savages in need of Roman civilization… the same enlightened, compassionate civilization that gave us the arena and crucifixion. The famous Lindow Man, whose strangled body was recovered from a bog in 1984, may have been a human sacrifice. He also may have been an execution, or a murder victim. We simply don’t know.

The Roman opposition to the Druids had nothing to do with their sacrificial practices and everything to do with the fact that the Druids represented a source of nationalistic rebellion against the empire. In 61 CE, the Romans attacked the Druid center on the island of Anglesey in Wales. The Roman historian Tacitus reported:

On the shore stood the opposing army with its dense array of armed warriors, while between the ranks dashed women, in black attire like the Furies, with hair disheveled, waving brands. All around, the Druids, lifting up their hands to heaven, and pouring forth dreadful imprecations, scared our soldiers by the unfamiliar sight, so that, as if their limbs were paralysed, they stood motionless, and exposed to wounds. Then urged by their general’s appeals and mutual encouragements not to quail before a troop of frenzied women, they bore the standards onwards, smote down all resistance, and wrapped the foe in the flames of his own brands.

What the Roman armies could not destroy, the coming of Christianity did. Druids lost their positions as priests, then as advisors, then as healers. By the 7th century, their only role was as bards who may not have known anything about their predecessors.

The Druids disappeared, but the image of the Druid remained in the culture of Britain.

William Stukeley was a medical doctor who later became an Anglican clergyman. He was born in 1687 and died in 1765. His interest in the megalithic monuments of Britain – most notably Stonehenge and Avebury – led him to attempt to reconstruct the religion of the ancient Druids. He had even less evidence to work from than we do 300 years later – what he produced was a speculative attempt to “reconcile Plato and Moses, and the Druid and Christian religion.” In a 1743 publication, he claimed that the Celtic god Lugh, the Egyptian Thoth, and the Greek Hermes were all forms of the Christian Holy Spirit.

Today this idea seems absurd. But Stukeley lived in a time long before Darwin’s work on evolution and geologists’ work on the age of the Earth – the literal truth of the Bible was still a reasonable theory. By connecting Druidry and other ancient religions to the Bible and to the proper Anglican Christianity of his time, he claimed them for his own. Druids were no longer the barbarian practitioners of human sacrifice as portrayed by Julius Caesar, they were forerunners of Christ, the British equivalent of the Hebrew patriarchs of the Old Testament.

I find Stukeley’s speculations objectionable both as a Pagan Druid and as a fan of honest history. But the end result of his work and the work of others like him was to make the Druids accessible to British and British-influenced culture.

Both before and after Stukeley, individuals with an admiration for the ancient Druids were calling themselves Druids. And it wasn’t long before these new Druids began forming Druid societies. My order, the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids, traces its origins back a meeting in a London pub in 1717. There’s no evidence that meeting actually happened, but there is conclusive evidence there was at least one Druid order in operation by 1792.

These early Druid orders were not religious – they were cultural and fraternal. They worked to preserve Celtic culture – in particular, Welsh culture – in the face of English domination. Some were fraternal orders, formed primarily for mutual aid – an early form of social insurance.

No discussion of the Druid Revival would be complete without mentioning Iolo Morganwg. Born Edward Williams in 1747, he had a deep nationalistic pride in his native land of Wales and a love of the Welsh bardic tradition. He was an excellent student of literature. He was not, however, particularly good with money. He failed at being a builder, a shopkeeper and a farmer, succeeding only in burning through his wife’s dowry. But in 1789 he published a collection of medieval Welsh poetry he claimed to have been given by a friend. The poetry was quite good, and Iolo had both the connections and the selling skills to turn it into a commercial success. Other volumes followed, bringing Iolo both notoriety and a steady income.

The poetry, of course, was not medieval Welsh. It was Iolo’s own work. But it was so good the deception wasn’t discovered for over a hundred years.

Iolo was also a founding member of the Unitarian Society of South Wales. His writing on religion shows his attempt to reframe Christianity in ways that will sound familiar to Unitarian Universalists two hundred years later. He said “God is one with life, and there is no life but God, and there is no God but life.”

In a written dialogue, he asked “Art thou of opinion that every living being shall attain to the circle of [the Upper World] at last?” And he answered “That is my opinion, for less could not have happened from the infinite love of God.”

These thoughts may not have come from the medieval Welsh or the ancient Celts, but they’re still good ideas. Had Iolo published his work as his own, today he would likely be known as one of the greatest Welsh bards in history. Instead, he is known as one of the greatest literary forgers in history.

The Pagan Druids

Let’s leave the Christian Revival Druids for now and pick up another historical thread, that of the origins of modern Paganism.

When Cynthia Talbot and I do our Introduction to Modern Pagan Religion workshop, we usually spend about an hour and a half on history. For our purposes this morning, let me simply say the roots of modern Paganism are many, deep, and intertwined. They include a dissatisfaction with the excesses of orthodox Christianity, a yearning for the feminine aspects of the Divine, and a re-examination of the stories of our ancestors – seeing the characters in the stories of the Greeks and Celts and Egyptians not just as mythological personas, but as actual gods and goddesses.

But perhaps the strongest root of modern Paganism is our connection with Nature. We now know we were not placed on the Earth as Genesis states, we grew out of the Earth – the Earth is our Great Mother. It took millions of years for humans to evolve from the simplest life forms – our species has been around for perhaps 200,000 years. Only in the last 10,000 years have we lived in cities, and we’ve lived in industrial societies for perhaps 200. We evolved living on the land and now we are isolated from the land. We have moved from our natural place in Nature to being separated from Nature.

Many of the early Unitarians responded to this separation. In his famous essay “Nature” Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote:

The greatest delight which the fields and woods minister is the suggestion of an occult relation between man and the vegetable. I am not alone and unacknowledged. They nod to me, and I to them. The waving of the boughs in the storm is new to me and old. It takes me by surprise, and yet is not unknown. Its effect is like that of a higher thought or a better emotion coming over me, when I deemed I was thinking justly or doing right.

Modern Paganism’s most prominent form has been Wicca, the religion of witchcraft, first promoted by, or perhaps, invented by Gerald Gardner in the mid-20th century. Wicca began as a mystery religion in the tradition of Freemasonry and the Golden Dawn. But it’s been said that after the first Earth Day in 1970, Wicca became a Nature religion. Its major holidays mark the turning of the seasons and its minor holidays mark the waxing and waning of the moon. While formal Gardnerian Wicca is still very much a mystery religion, the tremendous growth in Wicca over the past 30 years has primarily been driven by books, by solitary practitioners, and by an emphasis on the sacredness of the Earth.

One of Gerald Gardner’s friends, fellow naturists, and sometimes editor was Ross Nichols. Gardner was a flamboyant man who never missed a chance to publicly promote Wicca. Nichols was a quiet, private man, but when he lost the election for Chief of the Ancient Druid Order in 1964, he formed his own order: the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids. Today OBOD is the largest Druid order in the world.

OBOD is not a Pagan order, although many of its members are Pagan in one sense or another. It is centered on spiritual growth, an affinity for Celtic culture and lore, and of course, a love of Nature. Some Druid orders are specifically Pagan, most notably Ár nDraíocht Féin – A Druid Fellowship – which is the largest Druid order in this country.

Nature

Modern Druidry comes out of our ideas about the ancient Druids and out of our yearnings for Nature.

In our time, we have not only a separation from Nature, but also the challenges of climate change, habitat loss and resource depletion. The idea that humans should have dominion over the Earth and that the only value of Nature is in what material wealth we can extract from it is quickly running up against very real and very unpleasant limits.

For all the good evolution has brought us, it has also left us with the impulse to do whatever is most appealing for ourselves here and now. Eat all you can when food is available because you never know when you’ll get to eat again. Have sex as soon as you can, to be sure you reproduce before a disease or a predator kills you. Take care of your tribe, but don’t spend any resources taking care of others – they don’t share enough of your genes. These impulses helped our ancestors survive in the wild. They’re not so helpful for those of us living in a time and place where food is plentiful, population is high and our success depends on cooperating with people who don’t look and sound and believe like us.

The spiritual aspects of Druidry help us deal with these conflicts between evolutionary urges and the realities of the modern world. A Druid triad says there are “three demonstrations of wisdom: holding to reason, holding to imagination, and holding to improvement.” We learn to examine our lives both objectively and compassionately, constantly looking to see if what we are doing is helpful to ourselves and others and in alignment with our highest values. We constantly ask ourselves “what if?” and “why not?” While we honor tradition, we refuse to trap ourselves in ways of living and being that no longer serve us well simply because they are familiar and comfortable. And we constantly look for ways to make things better. Improvement doesn’t mean “more.” It means “better,” so we learn to recognize when we have enough.

The cultural aspects of Druidry help us answer the basic human questions “who am I?” “where do I come from?” and “how should I live?” We are people who like Pwyll [Pooeelh] keep our word and honor our bargains. We value peace, but like the Fianna we will not shrink when fighting is necessary. Like Cerridwen we love our children no matter how ugly they are, and like Gwion Bach we work diligently for the Awen, the inspiration that comes in its own time and not when it is convenient for us.

These stories do not belong exclusively to those of us who can trace our family history back to Ireland or Scotland or Wales. They belong to everyone who hears their call and responds.

The Nature aspects of Druidry teach us that the Earth is our Mother, and we should treat her with the honor and respect we give our human mothers. Some advocate caring for the Earth and her creatures because we only have this one planet. That’s good, and if you do the right things I don’t particularly care why you do them. But how much stronger is our commitment to Nature when we form and maintain a spiritual connection with Nature? How much easier is it to see Nature when we spend time in Nature? How much more effectively can we honor and care for Nature when, in the words of Henry David Thoreau, we “live deliberately?”

For some Druids, this involves a reciprocal relationship with the spirits and gods of Nature. For others, it involves environmental activism. For all, it involves mindfully considering how we live and the effects our lives have on other creatures, various ecosystems, and the Earth as a whole.

There is value in going outside and digging in the dirt. There is value in going outside and looking up at the sun and moon and stars. There is value in going outside and watching the squirrels and listening to the birds. There is value in going outside – are you starting to see a pattern here? – and smelling the flowers, lying in the grass, and hugging the trees. This can be challenging in the miserable Texas summers… just as it can be challenging in the miserable Minnesota winters. But when we have a spiritual relationship with Nature, these challenges become something to work with and work around. When we have a spiritual relationship with Nature, maintaining that relationship becomes more important than constant comfort: we learn to go walking before dawn, to greet the rising sun before we begin our work day, to speak to the trees as soon as we get home, and to salute the moon before we go to bed.

There is no Druid orthodoxy and there is no one right way to honor Nature. There are many ways – find the one that speaks to your soul.

If you feel the call of Nature, I implore you to not let the desire for perfection and purity keep you from doing what you can, today. The mainstream American lifestyle is not sustainable. Making small changes today delays the depletion of fossil fuels and reduces the damage done by burning them. Despairing because you cannot reduce your carbon footprint to zero accomplishes nothing.

Our love for Nature is not a naïve love. The Earth is our Mother, but stand in the path of a tornado or walk through the desert without water and our Mother will kill you. We are part of Nature and we have a place in Nature, but that place is not at the head of the table. In a later portion of the essay I read earlier, Ross Nichols said:

Man is in action governed by emotive beliefs. If the weekender is merely living out the essentially selfish creed of the romantics, to bring about a different, humbler approach a different belief needs to be inculcated… and this is where myth enters.

The myths of dominion, of manifest destiny, and of perpetual progress have moved us to do wonders, but they have reached their limits. We are driving through the desert and we are quite literally low on gas. Our world is in need of new myths, and the myth of the Druid stands ready for us to reimagine it for this new time.

Becoming a Druid

Spiritual growth, cultural exploration and a reverence for Nature are things most people in a UU church would view as good. But should we call it Druidry? I get this question periodically: how can you call yourself a Druid when we know so little about who the ancient Druids were, how they trained and worked and worshipped? How can you claim a connection to the ancient Druids when Druidry disappeared for a thousand years?

This is a fair question. Answering it begins with the understanding that even if the ancient Druids hadn’t been wiped out, they would have changed. Druids would not be advisors to kings because kings have been replaced by presidents and prime ministers. Druids might be healers, but we would still have doctors and hospitals and general anesthesia. Druids might be keepers of lore, but they would use iTunes and YouTube the same as the rest of us. The fact that today’s Druids do not do exactly what our ancient namesakes did does not mean we cannot legitimately call ourselves Druids.

I didn’t become a Druid because I thought it was cool or because I thought I would become powerful or even because I thought it would be helpful and fulfilling. I became a Druid because I was called to Druidry. When I first read about it, something inside me clicked – I knew this was what I was supposed to be and do.

If I was called to Druidry, then who or what issued the call? Might it be the very same goddesses and gods, the very same ancestors, the very same spirits of Nature that called the ancient Druids? Might they call us to learn similar skills to fill new roles in this new time and place? Might these roles look very similar to what Druids would be doing if they had never been wiped out and had instead continued on in lines that were unbroken but in roles that had evolved to meet the needs of contemporary society?

Historians continue to dig for facts about the ancient Druids and to form hypotheses and theories about who they were and what they did. Various Druid orders have different areas of emphasis, different training programs and different criteria for membership. This is valuable work and I support it all. But in the end, it doesn’t matter. I know what I’ve been called to do and what I’ve been called to become. Name it what you like. I like “Druid.”

The Art of Wild Wisdom

The title of this service comes from Thea Worthington, who holds the office of Modron in the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids. In a discussion on definitions, she said “Druidry is the art of wild wisdom.” It’s the spirituality Nature teaches us, if only we’ll slow down, go outside, and listen.

The art of wild wisdom is staring up at the night sky and realizing the Universe is so vast and old and we are so small and brief, and yet here we are, contemplating it all.

The art of wild wisdom is the moon moving from full to dark to full again; it’s the sunrise on the Summer Solstice when the days are long and the sunset on the Winter Solstice when the days are at their shortest.

The art of wild wisdom is the miracle of life joining with life to create new life.

The art of wild wisdom is the inspiration of the hawk, the passion of the stag, the wisdom of the salmon and the power of the bear.

The art of wild wisdom is the bear, and the wolf, and the snake, all of whom will kill you if you are not very careful.

The art of wild wisdom is the hurricane and tornado, the earthquake and wildfire, the blizzard and the flood.

The art of wild wisdom is the knowledge that Nature is beautiful and terrible, creative and destructive, and we are a part of it all.

In the last chapter of his book Druid Mysteries, OBOD Chosen Chief Philip Carr-Gomm offers these words:

The call to [Druidry] is being heard again – throughout the world – because it represents not an eccentric, irrelevant and atavistic belief system, but an approach to life that can unite the spiritual and the artistic, the environmental and the humanitarian concerns we share, the thirst for connection with Mother Earth and Father Sun – the need for a powerful spirituality, and the need for a down-to-earth, sensual, fully human connection with our bodies and the body of our home, the Earth.

May it be so.