November 28 marks an uncertain but important anniversary: 300 years of modern Druidry.

On November 28, 1717, the Ancient Druid Order was founded at the Apple Tree Tavern in London. Or at least that’s what Ross Nichols – the founder of the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids – said in The Book of Druidry.1 Historian Ronald Hutton says there’s no evidence this meeting took place and puts the first documented Druid order as beginning in 1792.2

So do we have anything to celebrate or not? Like Christians arguing over whether Jesus was really born on December 25 (it’s uncertain but unlikely), finding the exact date is less important than picking a date and celebrating.

The re-imagining and re-creation of Druidry is very much worth celebrating.

The Ancient Druids

There is very little we can say with certainty about the ancient Druids. Based on the evidence we have, we think they were judges, healers, and keepers of records and lore. They were probably priests, though how closely they resembled the temple priests of the Greco-Roman world is difficult to say. Whatever they were, they were important enough for the Romans to go to the trouble of wiping them out in the Anglesey massacre of 61 CE. The Roman historian Tacitus reported:

On the shore stood the opposing army with its dense array of armed warriors, while between the ranks dashed women, in black attire like the Furies, with hair disheveled, waving brands. All around, the Druids, lifting up their hands to heaven, and pouring forth dreadful imprecations, scared our soldiers by the unfamiliar sight, so that, as if their limbs were paralysed, they stood motionless, and exposed to wounds. Then urged by their general’s appeals and mutual encouragements not to quail before a troop of frenzied women, they bore the standards onwards, smote down all resistance, and wrapped the foe in the flames of his own brands.3

What the Roman armies could not destroy, the coming of Christianity did. Druids lost their positions as priests, then as advisors, then as healers. By the 7th century, their only role was as bards who may not have known anything about their predecessors.

The idea of underground survivals is attractive and therefore persistent. In The Book of Druidry (1975) Ross Nichols wrote:

Intermittent recognition of Druidry as a possible philosophic system or a local cult seems to have occurred from time to time since AD 1245 and obviously the tradition went on in hereditary groups who kept it to themselves.

Yet there is no evidence for these “obvious” hereditary groups, and it seems highly likely at least one would have come out of the shadows by now. As with the claims of witchcraft survivals from ancient Paganism, the claims of hereditary Druidry reflect a deep desire for continuity and a few cultural survivals, not actual institutional continuity.

The Revival Druids

Druids disappeared from the apparent world for close to a thousand years. But the memory of Druids and the concept of Druidry remained alive. As Europe began to emerge from the Middle Ages, people looked back to antiquity to answer the universal questions of “who are we?” and “where did we come from?” For many people, this meant looking back to the Greeks and Romans. But in Britain this also meant looking back to the Druids.

The problem was that while there were ample written accounts of Greece and Rome, there was virtually nothing from pre-Roman Britain. As Hutton points out in The Druids4 this made the Druids a blank slate who could be imagined many ways, from bloodthirsty savages to peaceful Nature worshippers to wise sages.

The 16th and 17th century Britons also had the matter of stone circles and other megalithic monuments scattered around their countryside. It was natural to connect these monuments with the Druids. It was also wrong. The ancient tombs and circles had been built, rebuilt, and abandoned centuries before the first Druids walked the land. I have to think the Druids used these monuments (how could they not?!) but any such uses are lost to history.

Nichols wrote:

It is the Order’s tradition that John Toland was the founder, not so much of this earlier renaissance as of the unity of many groves, which unity is given as having begun in 1717.

In The Earth, The Gods and The Soul Brendan Myers says there’s no reason to think Toland (1670 – 1722) founded an order or a “unity of many groves” but he expressed many ideas of interest to Druids, namely pantheism.

The society of the time was thoroughly Christian, so most of the Revival Druids attempted to harmonize their thoughts about the Druids with their Anglican Christianity. This didn’t work so well, as when William Stukeley (1687 – 1785) attempted to “reconcile Plato and Moses, and the Druid and Christian religion.”5

No account of the Revival Druids would be complete without mentioning Iolo Morganwg (1747 – 1826). He had a deep pride in his native land of Wales and a love of the Welsh bardic tradition. He claimed to have found and translated several volumes of ancient Welsh poetry – in reality it was his own work. But it was so good the deception wasn’t discovered for over a hundred years, and while his work isn’t authentically ancient it is authentically Celtic, and it has inspired Druids and others for two hundred years.

Modern Druids

Current OBOD Chosen Chief Philip Carr-Gomm has an excellent History of Modern Druidism on the OBOD website. I’m not going to try to duplicate his work.

What’s important to know is that the Druid societies of the 19th and early 20th centuries were almost entirely cultural or fraternal. The cultural Druids were interested in reviving and promoting Celtic culture and literature, especially the idea of the Eisteddfod. There are pictures of Princess (now Queen) Elizabeth being initiated into a Druid society – these were cultural Druids.

The fraternal Druids were either social clubs or friendly societies – groups formed to provide insurance to its members. These were quite common a hundred years ago. The rise of Social Security and employer-provided health insurance in the United States and universal health coverage in virtually every other civilized country eliminated much of the need for friendly societies.

The idea of Druidry as a spiritual path did not become widespread until the second half of the 20th century.

Druidry Today

There are many Druid orders. I’m a member of two and I’m familiar with a third.

The Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids (OBOD) is the largest Druid order in the world. OBOD teaches a set of spiritual technologies that are compatible with most any religion, though its material is presented in a Pagan context. Its correspondence course is excellent. The Bardic grade is an introduction to spiritual practice. The Ovate grade covers healing, seership, and deep inner work. The Druid grade ties it all together as it teaches leadership and service. I’m a full member of the Druid grade in OBOD.

Ár nDraíocht Féin (ADF) is the largest Druid order in the US. It was founded by Isaac Bonewits in 1983 to be “a Pagan church based on ancient Indo-European traditions expressed through public worship, study, and fellowship.” If you want the best chance of finding a local grove in the US, or if you want an explicitly Pagan approach, try it.

I’m an ordinary member of ADF – I hold no rank or office. If I had unlimited time I would pursue ordination in ADF, but I don’t have unlimited time and I already have an earned ordination. I’m a member because I support ADF’s mission and vision.

The Ancient Order of Druids in America (AODA) emphasizes “nature spirituality and inner transformation founded on personal experience.” It’s much smaller than OBOD and ADF, and it’s more closely aligned with the Revival Druids. I’m not affiliated with AODA, but I know enough people who are to recommend them to those who might be interested.

None of these orders are “best” – the question is which one is the best fit for you.

The Future of Druidry

In a post earlier this year I said “Druidry is the attempt to recreate, reimagine, and reconstruct the religion of the ancient Druids.” Over the past 300 years that attempt has taken many forms. This is as it should be – if a religion or spirituality is to remain relevant, it must speak to the lived experiences of people where and when they actually live their lives.

Today Druidry is most commonly associated with Nature spirituality. Given our on-going environmental crises, I can think of no more necessary and useful context. And – particularly as practiced in ADF – Druidry is associated with contemporary Pagan religion. Given the slow but steady decline of orthodox Christianity, Druidry has the opportunity to reach a relevance not seen since the days of the original Druids.

Because whatever Gods and spirits called to the ancient Druids are calling to us today. The different Druid orders are different ways people have answered that call. What you read here on this blog week after week is how I answer it, at least in part. My oracular skills aren’t good enough to see what Druidry will look like after another 300 years, but of this I am certain: Druidry will continue to thrive.

Happy 300th birthday to the modern Druid movement.

May there be peace in the North.

May there be peace in the South.

May there be peace in the West.

May there be peace in the East.

May there be peace throughout the whole world!

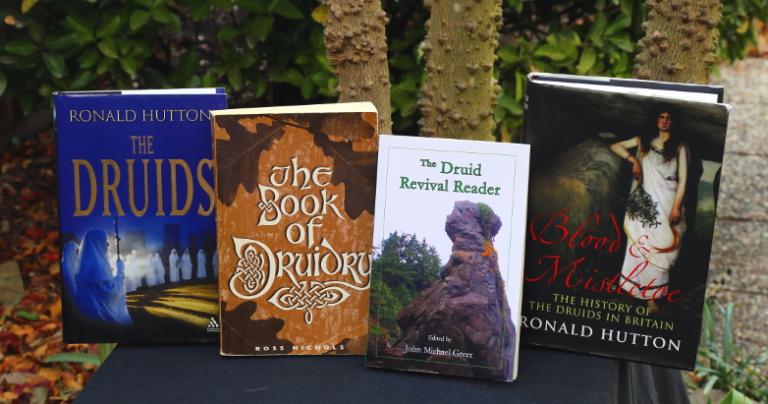

1 The Book of Druidry by Ross Nichols, Thorsons Publishers, 1975.

2 Blood and Mistletoe: The History of the Druids in Britain by Ronald Hutton, Yale University Press, 2009.

3 The Annals by Tacitus, 14-68 CE.

4 The Druids by Ronald Hutton, Hambledon Continuum, 2007.

5 The Druid Revival Reader edited by John Michael Greer, Lorian Press, 2011.