Loving Nature in Tornado Season

The Denton Unitarian Universalist Fellowship

March 21, 2021

It’s easy to love Nature in the Spring. The days of it getting dark at 5:30 are long past. The cold weather – and we certainly had some this year – is pretty much gone. The browns and greys give way to greens. There are new flowers and budding trees… and it’s not ridiculously hot yet. Spring is beautiful.

One of our UU principles is “respect for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part.” We don’t see Nature as “fallen.” We see Nature as sacred and holy, something to be honored, respected, and enjoyed. We love Nature.

And then tornado sirens go off.

On average, there are 1200 tornadoes in the United States each year, causing 1500 injuries, 80 deaths, and 400 million dollars in damages. Texas has more tornadoes than any other state – here in North Texas we average 25 per year. Tornadoes are usually brief and localized, but where they strike, the results are devastating. Tornado warnings give only a few minutes to take shelter, and that’s with the massive improvements we’ve seen in tornado forecasting over the past 20 years or so.

The same Nature that gives us trees and flowers and warm Spring days also gives us tornadoes. It’s hard to love Nature in tornado season. But we can, and I think, we should.

The Four Centers of Paganism

Today’s service is planned and presented by CUUPS, the Covenant of Unitarian Universalist Pagans. CUUPS at the national level was recognized by the UUA in 1987 – Denton CUUPS was formed in 2000, by and for Pagan-friendly UUs and UU-friendly Pagans. CUUPS does many things, most notably providing rituals and celebrations for the eight holy days on the modern Pagan Wheel of the Year. That includes the Spring Equinox, which was yesterday. We also lead the occasional Sunday Service, as we do today.

Defining modern Paganism is difficult, because it’s very broad. In 2013 some of us took a religious studies approach and described Paganism as a religious movement with four centers – four different places where people find the Divine… however people understand the Divine. Those four centers are Nature, the Many Gods, the Self, and Community.

Today’s service is grounded in Nature-centered Paganism. And it’s especially grounded in our Nature-centered creation myth.

A Nature-Centered Creation Myth

Contrary to what some think, a myth is not a “made up story.” Myths often have elements of history in them, but a myth is not inferior to a historical account. As the quote of indeterminate origins says “a myth is a story about things that never were but always are.” I like say that a myth is a story to live by. A myth tells us who we are, where we came from, and how we should live.

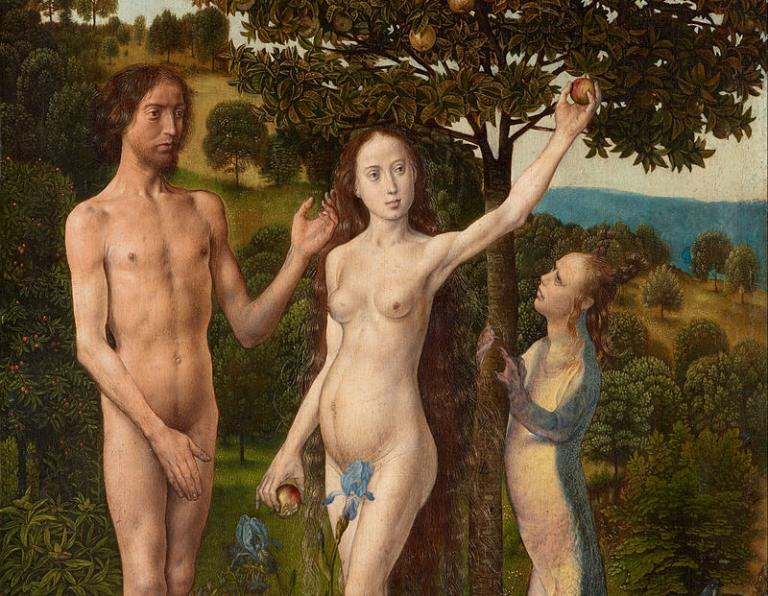

Most cultures – though not all – have a creation myth. The creation myth of the Western world for the past two thousand years or so says there was a time when the Earth was perfect and there was no suffering. And then some humans did something they weren’t supposed to do, and now the world is fallen and has sickness and death and tornadoes in it.

Religious and literary scholars have different ideas about the origins of that myth and on what truths it’s trying to communicate. Dismissing it because it’s not literally true would be a mistake. But there’s another creation myth that’s more helpful to us here and now.

There was a time, around 14 billion years ago, when all matter and energy was compressed into an infinitely small point. And then there was a Big Bang, and it began to expand. Particles combined into elements, elements combined into stars and stars combined into galaxies. Planets began to form, and then about three and a half billion years ago, life began on Earth.

We still don’t know how life began, but once it did, it began to expand and evolve, a process that continues to this day. Every living thing on Earth – including you and me – is a descendant of that first single-celled organism.

We are all related. We share almost 99% of our DNA with chimpanzees, 98% with gorillas, 90% with cats, and 50% with bananas. When Saint Francis called the wolf his brother, he had no way of knowing just how right he was.

Our line split from the chimps and bonobos about 4 million years ago, and our species is perhaps 200,000 years old. We’re the newcomers. And yet we often think and act as though the world is supposed to be all about us.

Myths tell us who we are and where we came from. The myth of the Big Bang and of evolution tell us that we came from Nature, and that we are a part of Nature. Perhaps more importantly, it tell us that we are not the center of Nature, nor are we its head. We are simply one part of Nature, one part among many.

Imago Dei and Animism

Many of us are familiar with the Christian concept of Imago Dei – the idea that we are made in the image of God. That idea has been used to justify exploiting the natural world, driving other species to extinction, and generally thinking we’re superior to everyone and everything else.

But the real problem with Imago Dei is not the idea that we carry the image of the Divine. The problem is thinking we’re the only ones who carry it. Our natural creation myth tells us that our origin is the same as the origin of rabbits and squirrels, rocks and trees, rivers and winds. Whatever it is that gives us life gives life to every other thing as well. We all carry the image of the Divine. And when we start to understand that the Divine is in us all, we start to appreciate the wisdom of animism.

When I was growing up I was taught that animism is a “primitive” religion, the first step on a journey to the “proper” religions of modern time. The fact is that animism is neither primitive nor a religion. It’s a way of seeing the world, a way that acknowledges our common origins. Animism says that everything is not a thing but a person, and we can relate to them as persons. Not as human persons, but as tree persons and squirrel persons and river persons.

I remember the first time I saw an elk – they were a lot bigger than I thought they’d be. It was a trip to Colorado in 2004 – the elk were coming out of the mountains and grazing in people’s lawns. The local news kept reminding people not to get close to the elk. They’re faster than you think, and while they’re herbivores, just because they won’t eat you doesn’t mean they won’t kill you if you get too close to them.

Are elk evil? I would take a very human-centric person to think that. The vast majority of times when humans are injured by elk or other wild animals it’s because we’ve ventured into their territory. Elk are persons who do what elk do. They have as much right to be here as we do.

Rabbits are persons who do what rabbits do. Rivers are persons who do what rivers do. Tornadoes are persons who do what tornadoes do. And we all are part of the Divine.

Loving Nature doesn’t mean liking tornadoes

Now, loving Nature doesn’t mean we have to like tornadoes.

Survival is an instinct – every creature on Earth wants to live. But many of us are in competition. Elk compete with deer for grazing territory – a competition the larger elk usually win. Elk are in a very different competition with wolves.

We like to speak of “survival of the fittest” and we talk about how competition strengthens a species. But biologists remind us that evolution has no foresight. Faster elk and stronger wolves are simply the by-product of elk and wolves doing what elk and wolves do.

I imagine the elk don’t like the wolves. We don’t have to like tornadoes. But would Nature be as beautiful without elk and wolves? Without snow and snowstorms? Without tornadoes? Without humans? We cause more damage to the natural world than any other species.

We are all part of Nature. We all do what we do. Sometimes we’re in competition. Sometimes we’re in conflict. We don’t have to like it. But if we are wise we will accept it for the reality that it is, and if we can, see the beauty in the amazing diversity and complexity that is Nature.

Using our greater intelligence

Our evolutionary advantages are opposable thumbs, bigger brains, and the capacity for speech and language. If we cannot see into the future, we can see where our current path is taking us. Other animals can assess risk when it presents itself – we can assess risk in the abstract, and thus take precautions to minimize it.

We tempt Nature when we live in dangerous places, and “Tornado Alley” is certainly one of them. But there is no place in North America where Nature doesn’t at least occasionally try to kill you. The Gulf and Atlantic coasts have hurricanes, the West has wildfires and earthquakes, and the North has blizzards that make what we experienced last month look like nothing. And while modern medicine has done wonders to increase our life expectancy, the Covid-19 pandemic reminds us that we will never be completely free from disease.

There is no “safe” place to live.

And so we respect Nature, and we understand that our place is not at the head of Nature, nor at its center. Rather, we are one species among many species. We give thanks for tornado sirens, and storm shelters, and bathtubs, and insurance, and all the other things that reduce our risk of dying in a tornado even though we can never completely eliminate that risk.

You get a lifetime

Perhaps the most difficult part of appreciating Nature is the unfairness of it all. Why are some born healthy and others not? Why are some born with all they need to succeed and others born with not even enough to survive?

Why do tornadoes demolish one house and leave the next house untouched?

Philosophers, theologians, and ordinary people have struggled with this for at least as long as we’ve been human. No one has a satisfactory answer. Author Neil Gaiman came perhaps closer than anyone when he had Death tell someone “you get what anybody gets – you get a lifetime.”

The world, the universe, life itself – it’s not all about humans. It’s certainly not all about you or me or any other individual, despite what certain politicians think of themselves.

And yet…

Go outside on a clear night and look up. Even through the Metroplex light pollution you can see stars and galaxies as far as two million light years away. Using one of the space telescopes we can see objects even further away – when the light you see left those galaxies, the Earth didn’t even exist.

The universe – Nature – is so very old, and so very large. We are so very new and so very small, and our lifetimes are so very brief. And yet, here we are, a part of it all, contemplating it all.

The same natural forces that produced stars and galaxies produced you and me. How can we look on Nature with anything but wonder and awe… and with love?

Seeing things as they really are

Storm chasers – people who actively seek out tornadoes, either to study them or just to watch them – are warned that if they want their videos to be used on the news or in a documentary, they need to watch their language. On one hand, the warning talks about the kind of profanity many of us instinctively use when an experience of some immensity of Nature leaves us at a loss for words. But they also warn the storm chasers to avoid describing a tornado as beautiful, or magnificent, or amazing. That beautiful, perfectly-formed funnel cloud may have just destroyed someone’s home, or killed their grandmother.

Nature can be both awesome and awful.

But the storm chasers, from their vantage point that’s emotionally distanced – if not always physically distanced – have a point.

Elk are beautiful animals, but they can be deadly. Rivers provide both spiritual inspiration and life-giving water, but they can also drown us. And let’s not forget that we humans can wipe out entire species and ecosystems without a second thought. Nature is beautiful and terrible in all its forms, including its human form.

And so we accept that tornadoes do what tornadoes do. We fear them, with that healthy fear that acknowledges that life isn’t all about us. We respect them, and we do what must be done to protect ourselves from them. We reach out to those harmed by tornadoes with compassion and with tangible action. Our species’ evolutionary strategy isn’t survival of the fittest – it’s cooperation and mutual aid.

It’s easy to love Nature on a warm Spring day. It’s harder to love Nature when the tornado sirens are going off. But it’s all the same Nature. Beautiful and terrible, live-giving and life-taking, and we’re a part of it all.

Benediction

Tornadoes, rivers, humans, elk… we’re all part of Nature. We’re all part of a 14 billion year story, a story that will continue for billions more years after we’ve moved on to whatever it is that comes after we die. The universe wasn’t made for us and it’s not all about us, but we get to experience it, and contemplate it, and be a part of it.

And that is truly Divine.

May you and yours be safe and well, now and in the days to come.