From the dawn of humanity, people have recognized that the death of a loved one is an significant event in the life of a family and of a community; an event that should be solemnized. What our barely-human ancestors did tens and even hundreds of thousands of years ago is not so very different from what we do today.

But are these rites for the living or for the dead?

Or perhaps, for both?

I grew up Baptist and I was taught that funerals are for the living. According to conservative Protestants, when a person dies they’re instantly in heaven or hell and nothing can be done to change that. Prayers for the dead were useless. The purpose of a funeral was to allow the survivors to mourn, to comfort them with visions of heaven – and to threaten any backsliders with the prospects of hell.

Once I started exploring different religions, I learned that other people – including many Christians – believe the dead can benefit from the prayers of the living.

And then I became a Pagan, and I learned that some traditions have elaborate rites to help the dead find their place in the afterlife and to confirm their new status as an ancestor.

I got two different questions on this topic in the last Conversations Under the Oaks. I want to present both questions and then discuss funerals from a Pagan perspective.

Hazel asked:

My father (who was an atheist) recently passed away, and he said he wanted his ashes scattered and that he didn’t care where because he’d be dead (fair!). So I’d like to do something meaningful to me, since the scattering is likely to be just me.

I’m also finding it close to impossible to maintain even my most minimal offerings and prayers right now, and I wonder if there are frameworks of mourning or even just thoughts about it that might help. It feels like my spiritual focus has shifted right now and I’m not sure whether that’s something I should be embracing or if forcing myself through the motions would help me more. I don’t feel exactly abandoned by the Gods but I feel distant.

Someone who wishes to remain anonymous asked:

A few years ago I decided, for reasons that aren’t relevant to the question, that I wanted a direct cremation. In the UK this means that there is no funeral service or wake. The body is taken by a funeral director and cremated when there is a space. The ashes are returned to the next of kin after a few weeks. I made my wishes clear to my family and I’m still comfortable with it.

However, I’ve heard/read various comments suggesting that a dead person’s spirit “needs” a funeral ritual in order to go where it’s supposed to go. Instinctively I feel that my ancestors will help me, and as a devotee of Hekate I don’t think She will let me go too far astray, so I don’t know if funeral rites are just part of an industry or whether they really do serve a spiritual purpose.

Death and what comes after is a mystery

Before we try to figure out what we should do for the dead, we need to know what happens after death. Where do the dead go? What do the dead encounter? Who are they with?

The only honest answer to all these questions is “we don’t know.”

As with all religious questions, our lack of ability to answer definitively need not and should not prevent us from forming tentative answers and then acting in alignment with them, so long as we respect other reasonable answers and so long as we remain open to new evidence, new experiences, and new lines of reasoning.

We have an obligation to respect the wishes of the dead – up to a point

If your grandmother wants a Baptist funeral, find a Baptist preacher and give her a Baptist funeral. If your atheist father wants no funeral, don’t hold a funeral. Some people want to be cremated, others find cremation sacrilegious. To the extent we can, we should honor and respect the wishes of the dead.

We should not do for – or to – them what we know they would not want done. I do not want a Christian funeral. If planning my funeral falls to my Christian relatives, they can find a Druid or a UU minister who can do it properly (and considering who that may fall to, I have every reason to expect they would). I find the Mormon practice of baptizing the dead highly offensive.

So is the practice of misgendering trans people in death, especially those who died because of lack of support for who they really are.

At the same time, the dead cannot dictate how the living feel and how the living need to respond. If you need to cry, then cry. If you need to gather with a bunch of friends and relatives and cry together, do it. What you do for you is categorically different from what you do for the dead.

We need to mourn

Separation and loss are real. Death is painful for those who remain and the American practice of “your three days of bereavement leave are over, now get back to work” is unreasonable and cruel. So is the pathologization of grief. We don’t need antidepressants to “get over” the loss of a loved one. We need time and family and community.

To be clear: I am not opposed to antidepressants – they have their place. But this isn’t one of them.

I’m not a mental health professional, but I am a priest who sometimes leads funerals and other rituals around death. What Hazel describes sounds like normal, ordinary, healthy grief – exactly what mourning rituals are designed to deal with.

My suggestion would be to do some sort of ritual along with scattering the ashes. In keeping with her father’s preferences, that could be entirely naturalistic: returning the body to the Earth from whence it came. Add a song, a poem, or some other way of saying goodbye. If you feel the need to do this alone, do it alone. But if at all possible, invite some friends or relatives over to support you afterwards.

The alternative is to keep it all bottled up, and that’s not a healthy thing.

We need to remember

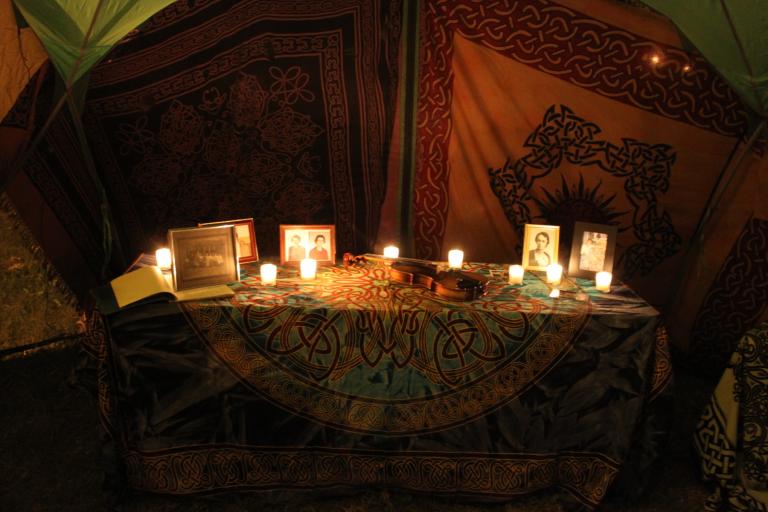

We need no supernatural beliefs to understand the truth of the statement “that which is remembered lives.” Whatever may have happened to our loved ones, there is no question that they live on in our memories. It is good to remember our beloved dead.

In the days and weeks immediately after death, remembering the good helps soften the blow of the loss. Funerals and memorial services help do this. In the months and years ahead, remembering honors our dead and allows us to keep loving them even though they’ve left this world.

We need to acknowledge the change that death creates

Death does not end our relationships, but it does change them. It transforms them. Someone who was a parent, spouse, sibling, or friend is now an ancestor. We once saw them face to face, now we see them only in photographs and memories. If we remember them they are still present in our lives, but that presence is different.

We need to acknowledge that difference, accept it, and reorder our lives around the new facts. Funerals and memorial services help us to process these changes and begin to learn to live with them.

Crossing over is a natural process

You need not believe that consciousness survives death to understand anything I’ve said so far. Pagans, Christians, atheists, and everyone else should be able to see the naturalistic parts of death and the benefits that funerals – good funerals, anyway – can bring to the living.

But for those of us who believe that we live on as individuals after death, there’s more. And that leads to the question of what funerals can accomplish for the dead.

Death is not the opposite of life. Death is the opposite of birth. Through birth we enter into this world, and through death we leave this world. Where were we before we were born? Do we return to the same place? I think we do.

And just as being born requires nothing on our part, so does dying. It’s a natural process. We go from where we are in this world to where we’re going in the next world. So to answer the final question directly, I do not believe we require funerals or other rites to get to where we need to go.

I expect that when my time comes, someone will come for me. It may be an ancestor. I have a grandfather and a great uncle who show up often in my ancestral devotions – I would not be surprised if they come to guide me to whatever is next. Perhaps Cernunnos will come for me – He’s been around me my whole life. Perhaps it will be the Morrigan. One of Her roles is that of psychopomp, and She holds my death.

And if none of them come? I’ve visited the Otherworld many times in journeying and in ritual. I know the way. It’s not hard to find.

Our rites can help the dead – if they need it

Still, almost every culture has its ghosts and restless dead. Those who die unexpectedly and/or violently may be disoriented and have trouble finding their way onward. Those who are worried about those they leave behind may be reluctant to move on.

Our funeral rites can help put them at ease. They say “yes, you are dead.” They remind them “you were loved and you still are loved.” They reassure them “we will care for your loved ones.”

In some cases, they say “we will see that you get justice” or “we could not stop this tragedy, but we will work to prevent such things in the future.”

Our rites tell the dead that it’s OK for them to move on, and thus make it easier for them to do so.

Some cultures and traditions teach that more is necessary. The Egyptians believed that preserving the body was necessary. Their rites included feeding the dead and providing them with objects and with servants. I’m not about to tell a 6000 year old (or more – likely more) culture that they’re wrong. If you are part of such a tradition, make arrangements for the necessary rites to be performed for you.

Egypt was not an egalitarian culture, and even in ancient times not everyone could be mummified. But Anpu is kind and Ma’at is just, and I trust They will help Their followers to find their way home.

Ancestral rites come later

Some traditions perform rites well after death to establish a person as an ancestral ally. The exact terminology and rites vary from tradition to tradition. My own belief is that the newly dead should be left alone (except for honoring them at Samhain and such) for two to three years, to give them time to adjust to being “over there.” After that, you may be able to ask for their help and establish an active link to them.

The phrase “funerals are for the living” is a Protestant and humanist idea that has no place in Paganism and polytheism. Funerals are for the community, which includes both the living and the dead. Let’s do what must be done for our dead and for their survivors, and in so doing, build a tradition that will be continued when we ourselves cross over.

For Further Reading

What To Do With My Body After I’m Dead (2019)

Sitting in a Bland Funeral Thinking About What We Should Do For Our Dead (2018)

One Pagan’s Thoughts on What Comes After Death (August 2017)

The Journey Into Spirit (2014)