I recently received an email seeking my contribution to a book wherein people prominent in various fields answer the question, “What (if anything) should public schools teach children about religion?” Among those who have already submitted their answer are former US President Jimmy Carter; John Hennessy (president, Stanford University); Kareem Abdul-Jabbar; Katharine Jefferts Schori (Presiding Bishop, Episcopal Church USA); Richard Dawkins (The God Delusion); Bernie Siegel, M.D. (and bestselling author); Jon Kyl (senate minority whip); Susan N. Herman (president, American Civil Liberties Union); Rabbi Norman Lamm (chancellor, Yeshiva University); Bob Coy (pastor, Calvary Chapel of Fort Lauderdale); and, I think we can all agree, most importantly, Julie Newmar, the original Catwoman.

I recently received an email seeking my contribution to a book wherein people prominent in various fields answer the question, “What (if anything) should public schools teach children about religion?” Among those who have already submitted their answer are former US President Jimmy Carter; John Hennessy (president, Stanford University); Kareem Abdul-Jabbar; Katharine Jefferts Schori (Presiding Bishop, Episcopal Church USA); Richard Dawkins (The God Delusion); Bernie Siegel, M.D. (and bestselling author); Jon Kyl (senate minority whip); Susan N. Herman (president, American Civil Liberties Union); Rabbi Norman Lamm (chancellor, Yeshiva University); Bob Coy (pastor, Calvary Chapel of Fort Lauderdale); and, I think we can all agree, most importantly, Julie Newmar, the original Catwoman.

Clearly, the editor of this book mistook me for someone actually august. Before he gets a chance to discover his mistake, though, I will send him my answer to his great question, and maybe it will accidentally end up in the book anyway. Stranger things have happened, I suppose.

What (if anything) should public schools teach children about religion?

The idea that kids in public schools shouldn’t be educated about religion is so stupid that I can’t even think about it without wanting to ram my head into a wall. Every upperclassman in every high school in the country should be required to take a class in world religions. Duh.

If ever it fell upon me to teach such a class, I would begin the first day of lessons by saying something like this:

Hello, relatively young people. Welcome to this state-funded, federally mandated class on religion. Isn’t it wonderful that we live in a country whose citizenry is not so amazingly dense that they actually think it would be okay to not teach young people about religion?

Whoo-hoo, America!

Anyway, about religion.

The reason that throughout all time people have adhered to all kinds of religions is because, as you are no doubt aware, life is insanely, unfathomably weird. The entire life system in which we’re all basically stuck makes barely any sense at all.

Think about it. First you have this massive, total nothingness. Then you just arrive, crying, hungry, and so helpless a geriatric Chihuahua with no teeth could kill you. Then you live as many years as you do, all the while trying to figure out what the whole deal is with life. Then you die, which, as far as you know, brings you right back to massive, total nothingness.

So, on your notes, write: Life = unknown blank, freakishly challenging life, death, unknown blank. Same for everybody.

Right? Nothing; crazy; nothing. That is life, in three words.

As you’ve also no doubt noticed, lots of stuff about life is awesome. Birds are pure greatness. Water: also a total winner. Birds in water always makes for a nice photograph. Music is also excellent. Being in love is fantastic; people love being in love. And good thing, or all our songs would be about birds in water.

But no matter how spectacularly rewarding life is or gets, the part of it that never at all feels right is the part where you, and I, and everybody else in the world has no idea what happens to people after they die.

Maybe you’ll burn alive forever. Maybe you’ll get reincarnated as an unfortunately ambitious squid. Maybe nothing at all will happen: maybe it’s just lights out, show’s over, you’re worm chow. Maybe you’ll get little wings, and spend eternity sitting on a cloud playing a harp, the sweet tones of which will probably stop driving you crazy after seventeen or so million years. Maybe you’ll end up a ghost haunting a lunch truck somewhere. Who knows?

Exactly nobody, that’s who. And that is the problem. You can assume that you know what happens to you after you die. You can believe that you know. You can hope that you know. But you can’t actually know in the way that we usually mean that word: it’s not empirically verifiable; it’s not a fact you can point to, and say, “I told you! Harp music! Bring earplugs!” If there is a God, he or she is definitely not showing their post-death cards. In the entire history of humankind, not once has a person come back from the dead, and gone, “Hey up there! I used to be Carl Mettnick, the barber from Cincinatti! Now I’m a potato bug! Reincarnation is real! I wish it weren’t! Don’t squish me!” No human has ever shown up three months after they died, going, “Turns out it’s tuba music! Can you believe it? I have pictures!”

Nothing like that has ever happened. And it’s not likely to this week.

The complete and impenetrable blank that exists at the end of every lifetime means that we are all forced to spend our lives ignorant of a knowable, clear context in which to understand our lives. We don’t know what if any existence we had before we were born, and we sure don’t know what’s going to happen to us after we die. And that fact makes you, and me, and all people everywhere acutely, profoundly, organically uncomfortable. To whatever degree we’re consciously aware of it (and mostly I think we’re not, since we do have to function in life), it renders the whole system we’re in too open-ended for comfort; it’s too loose, too mysterious about too much that’s too important.

It makes life, in a word, frightening. Not knowing what’s going to happen to you after you die is one hundred percent, fully unsettling—not to say terrifying.

And what do any of us need when we’re afraid?

We need comfort. We need security.

We need to know that everything is going to be all right.

Providing exactly that sort of comfort is the purpose and function of religion. That’s what religion does; that’s what religion is.

A religion provides to its adherents answers to all of the big, primary questions about life to which most people desire answers.

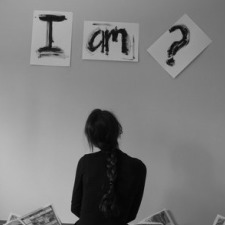

Who am I? What’s my core identity? Why was I made? Who made me? Who made the world?

And what, oh what, will happen to me after I die?

A fleshed-out, comprehensive, time-cured theology of a religion is certainly not the only means of arriving at satisfactory answers to those sorts of gargantuan life questions, by the way. Lots of people get all the spiritual and psychological comfort they need from agnosticism or atheism. And we’ll talk later about that. Suffice it to say for now that science—and the entire logical system upon which it is based—really is the gift that keeps on giving.

But for a lot of people—for, by far, most people—it’s through religion that they find solace from so much of life that is so brutal and frightening—as well as affirmation of so much of life that feels so, well, divine.

The idea of a benevolent, fair, all-powerful God comforts people in their despair, informs their highest inspirations, and generally helps and guides them at all times in between. Living inside the reality of an overarching divine power is always a serviceable context for understanding and processing the vagaries of life.

Religion really works for people, is the bottom line. That’s why they like it.

Next time I want to talk to you about two things. The first is that I am not saying that religions are man-made. I’ve been talking about the functions of religions, not their origins. Next time we’ll talk about how reasonable it is, or isn’t, to posit that the entire concept of God is based on anything but human imagination and need.

I, for instance, am a Christian. Does that mean that I’m insane, or in some way willingly deluded? Must anyone be who believes in God?

The second thing we’ll discuss is something that I first want you to guess at. The next time we meet, I’d like you to offer at least a decent guess to this question: What quality of any given religion can easily render it the most dangerous thing in the world?