The western sun eased into the Pacific Ocean shortly after 4:15 p.m. By the time I walked out of the newsroom at 5 p.m., the winter sky was cave dark. I called the house and told Tim that I wouldn’t be home for dinner. I had an interview with a family in Milton-Freewater.

The western sun eased into the Pacific Ocean shortly after 4:15 p.m. By the time I walked out of the newsroom at 5 p.m., the winter sky was cave dark. I called the house and told Tim that I wouldn’t be home for dinner. I had an interview with a family in Milton-Freewater.

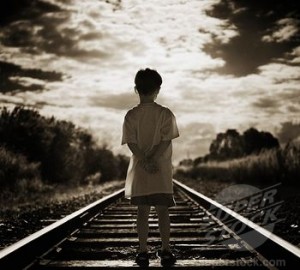

“Remember that teenager who got hit by a train? She’s coming home, tonight.”

The stucco house with the arched doorway and tiled roof was edged with evergreens. An outside light was turned on, proof that its occupants were expecting someone. I grabbed my notebook, a couple of pens, and trod up the brick walkway. A woman wearing a white blouse and black skirt greeted me.

“He’s gone to get her,” she said, speaking of her husband and her step-daughter. “C’mon in.”

She offered me a cup of hot tea. I took it.

Yellow light from the corner lamp gleamed off the red oak floors. Throw pillows fringed in burgundy and gold sat rigidly against the backs of wooden chairs and in the corners of the couch. A bible, big as a boot box, sat closed on the coffee table.

We made small talk and waited for the homecoming. I collected some of the story. Amber was 10 when her parents split up. The divorce was traumatic for the girl raised up under rigid religious beliefs. There was no room for errors of such magnitude in her life. She grew angry at her father, her mother and her God.

When her father remarried 2 years later, she went into a full-blown rebellion.

“That’s when Amber started drinking,” her step-mom explained.

The drinking led to sexual encounters. By age 14, Amber was pregnant. Because of their faith tradition, abortion wasn’t an option. And, truth be told, adoption wasn’t encouraged.

Her parents hoped that motherhood would entice Amber into giving up her partying ways, but it didn’t. No one knows for sure if Amber was trying to kill herself the night she walked in front of that oncoming train or if she was just so drunk she never heard the frantic whistle. Whatever the case, no one expected her to live. The train engineer had seen her there on that track and thrown the brake. Still, the train struck her fierce enough to send her end-over-end. She lived, but just barely.

Her parents hoped that motherhood would entice Amber into giving up her partying ways, but it didn’t. No one knows for sure if Amber was trying to kill herself the night she walked in front of that oncoming train or if she was just so drunk she never heard the frantic whistle. Whatever the case, no one expected her to live. The train engineer had seen her there on that track and thrown the brake. Still, the train struck her fierce enough to send her end-over-end. She lived, but just barely.

The phone rang. Father and daughter were in the driveway. This was Amber’s first trip home after eight months of therapy. Would her son, now nearly 3, recognize his mother? Would she be able to mother him?

Amber’s step-mother stepped outside. I waited inside, wanting to give the family a moment together. Wielding a wheelchair takes some time for the unaccustomed. Fifteen minutes passed. Time I spent thanking Jesus that that to date none of my four teens had become as self-destructive as Amber.

My husband and I could take little credit for that, for while we’d managed to hold our marriage together, there was many a day when we held on solely because grasping to a fraying covenant was all we knew to do. I was keenly aware that families fall apart because of seemingly insignificant acts of carelessness. The phone call ignored. The dinner that sits cold. The missed choir performance. The laundry that piles up in the basement like disagreements neglected. The thank yous never spoken.

My husband and I could take little credit for that, for while we’d managed to hold our marriage together, there was many a day when we held on solely because grasping to a fraying covenant was all we knew to do. I was keenly aware that families fall apart because of seemingly insignificant acts of carelessness. The phone call ignored. The dinner that sits cold. The missed choir performance. The laundry that piles up in the basement like disagreements neglected. The thank yous never spoken.

I heard Amber before I saw her.

“I love you, Daddy,” she said.

“I love you, too, honey,” her father answered, as he lifted her wheelchair over the door-jam and guided her to a spot near the couch his wife had cleared. The chair made the living room appear cramped. The arched doorways to the kitchen and the hallway where the bedrooms were located didn’t appear to be handicapped-accessible. I wondered if Amber’s father would have to carry her into her bedroom.

Amber’s dark chestnut hair was cut short, choppy. As if maybe her own son had snuck into her room one night armed with a pair of safety-scissors and whacked away as his mama slept. It was the result, I knew, of having had her head shaved.

Her skin was the pasty-white of Elmer’s glue. Her petite frame drawn to a C, curled down over her core. She could move her arms, but her fingers unwittingly balled into her palms.

I stood up.

“Welcome home, Amber,” I said.

She smiled and I saw a hint of the spunky gal she had been, before the alcohol, before the birth of her son changed her from daughter to mother, before the so-called friends cheered her outrageousness, before the train that blindsided her.

She smiled and I saw a hint of the spunky gal she had been, before the alcohol, before the birth of her son changed her from daughter to mother, before the so-called friends cheered her outrageousness, before the train that blindsided her.

Taking out a handkerchief from his back pocket, Amber’s father wiped the sweat from his brow. A slight man, with wire-rimmed glasses and graying hair, he possessed a jump-to-it demeanor common to men who’ve served in the military or among people eager-to-please.

He sat in a straight-back chair pulled up next to his daughter. I sat on the edge of a Lazy-boy chair. Amber’s son edged past his mother, past us and into the arms of his grandmother.

“I love you, Daddy,” Amber called out.

“I love you, too,” he answered.

They sounded like two parrots mimicking one another.

They sounded like two parrots mimicking one another.

“Is this hard for you?” I asked.

“Hard?”

“Yeah. To see your daughter this a’way?”

He pushed his glasses back on his nose and smiled broadly. “No. I’m am so glad to have my sweet little girl back.”

“But don’t you miss …” I struggled to find the right words to describe what I was witnessing.

“Not at all,” he said, reaching over and taking hold of his daughter’s curled up hand. “I’d been praying for God to send something to stop Amber from her rebelliousness. I just didn’t expect it to be a train.”

My gut seized up. Did this man really think God had sent a train to derail his daughter from a self-destructive path?

“You think this incident was an answer to prayer?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said, confidently. “It was God’s way of stopping Amber.”

Hard as I tried, I could not for the life of me figure out why any father, would be glad to see his daughter in a such a state.

“But don’t you think you’re going to miss the girl that Amber was?”

“Oh, no!” he answered. “Amber had been so rebellious, so full of anger. God’s given me back my sweet little girl.”

Or a Chatty Cathy doll, I mused, as Amber called out for the umpteenth time that night, “I love you, Daddy.”

“I love you too, baby,” he replied.

As I drove home past the moonlit stubbles of wheat fields, I wept for Amber and the independence  she lost the night she walked into the path of an oncoming train. She’d struggled mightily but now her fight was all give out. All that remained was a shell of the feisty girl she had once been. A girl without a will of her own.

she lost the night she walked into the path of an oncoming train. She’d struggled mightily but now her fight was all give out. All that remained was a shell of the feisty girl she had once been. A girl without a will of her own.

I don’t recall the exact words I prayed that night but I do recall the overwhelming gratitude I felt for God who had loved me enough to grant me free will. Amber’s daddy was wrong. God did not send that train to slam upside his daughter.

People make errors in judgment every day. I do it. You do it. Sometimes those errors create minor annoyances, like when we are caught and ticketed for doing 45 in a 35mph zone. Sometimes, though, those errors can be life-altering, like when we take the corner too fast and veer off the road into a telephone pole, crushing our spine or breaking our necks in the process.

That’s not God’s way of forcing us to slow down. It is simply the result of our own poor decision-making. But like Amber’s daddy, many times we make God the fall-guy for our mistakes.

God could have created us to be a people parroting our affection to him every five minutes, if he wanted, but where’s the joy in that?

The God of Abraham is not a bully or some demented train conductor gleefully mowing us down, just for the sheer humor of it all. He’s the coach, standing along the sidelines, clapping and cheering “Way to go!” when we get it right, and when we stumble, he’s grimacing and chiding us to, “THINK about what you are doing!”

God longs for us to be a THINKING people. A people who, after much consideration, might choose to declare our devotion to the God of all Creation.

Or not.

Either way, the choice is ours to make.

(Excerpt from Where’s Your Jesus Now? Zondervan)