In Jonathan Odell’s newest release, THE HEALING, Mississippi plantation mistress Amanda Satterfield loses her daughter to cholera. Distraught, Amanda steals a newborn from one of her slaves and renames the baby Granada. Troubled by his wife’s declining mental state, Master Satterfield purchases Polly Shine, a slave reputed to be a healer. But Polly’s sharp tongue and troubling predictions cause unrest across the plantation. Complicating matters further, Polly recognizes “the gift” in Granada, the mistress’s pet, and a domestic battle of wills ensues. Join author Karen Spears Zacharias as she discusses THE HEALING with novelist Jonathan Odell.

KAREN: How did the story of THE HEALING first present itself to you?

JONATHAN: While doing research for my first novel, which included interviewing hundreds of older black Mississippians, I kept hearing stories about the old-timey midwife and how crucial she was to the community. People held her memory in great reverence. When I delved into the history of the black Southern midwife, I found a thread that led all the way back to Africa, before the slave trade. And later, the traditions of midwifery sustained the community during the grim days of slavery and Jim Crow. It was also a source of pride and identity through generations of African Americans, before being supplanted by the white medical establishment.

Secondly, while doing research on black midwives, I discovered that my great-grand mother was a midwife, and was responsible for the death of her stepdaughter, my father’s mother, through a botched abortion. My dad did not learn about this until he was in his 70’s. He had been raised by his grandmother midwife, but never knew about the hand she played in his mother’s death. This intrigued me. What was it like for that woman to raise the child of the woman she was responsible for killing?

KAREN: What intimidated you about the telling of this story?

JONATHAN: A black friend, upon finding out that I was writing a book with black characters, admonished me, “Don’t you dare write another TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD!” I was shocked. I told him I loved that book. He said, “Most white-folks do.” He said it gave white folks the chance to feel good about some white savior rescuing a poor, pitiful black man. It didn’t threaten white superiority. He told me he did not want his children to read one more book about the downtrodden, helpless black victim who needed saving by the white man. He encouraged me to come up with a black hero who didn’t need saving.

That was the challenge I took on with writing THE HEALING. Of all the kind reviews I’ve had on this book so far, I think the comment I’m most proud of came from a Goodreads’ reviewer. She said, “I loved that this was a story about the black person’s experience that did not have a good-hearted white person come to the rescue and resolve all the problems.”

I wish I could put that on the dust jacket!

I’m also thrilled that several colleges have already decided to use THE HEALING in their African American classes. One nursing university will be using it with all their students.

KAREN: Did you have any misconceptions that you had to overcome in order to write THE HEALING?

JONATHAN: I was raised on the myth that “granny” midwives were dirty, ignorant and superstitious. I was shocked, and then later angered, to find out that I was the victim of a campaign orchestrated by state legislatures and the medical establishment beginning in the 1930’s to discredit the midwife. With the advent of public health services, these midwives stood in the way of centralizing control within white institutions. I was dumbfounded when I read in the American Journal of Public Health that the infant mortality rates among the midwives were half that of the white doctors who replaced them. Of course that makes sense! These women were culturally, psychologically and spiritually in tune with the patient and the community, in a way an outsider could never be. Their practices are being resurrected by birthing professionals today. Many of the herbs are now packaged and sold by pharmaceutical companies. When I discovered this, I knew I needed to investigate this story before it was forgotten. I had hit upon a narrative of heroism that was not dependent upon white initiative, pity or benevolence. It stood on its own.

KAREN: How did you go about conducting the research for THE HEALING?

JONATHAN: There’s an old joke that goes, “I love writing. It’s the paperwork I hate.” That’s true for me. I would rather research than write, to track down the truth through the annals of history. I interviewed surviving midwives, many in their 80’s and 90’s along with their families and community members, the children they had birthed and mothers they had treated. I spent hours in college oral history departments. Scoured the records in the basements of county courthouses. Studied the WPA slave narratives. And subjected my own family to merciless inquisitions! I found and interviewed white Mississippi families who still lived on plantations that their ancestors used to drive slaves on. I stumbled upon one surprise after another.

I remember interviewing one very old, ailing partially paralyzed white man who still lived in the antebellum plantation house, long after his family had lost the land. While we visited he was being spoon-fed by a black woman who must have been as ancient as he. Between sips, he told me that his great-great-great grandfather had cleared the Delta swamps with his own hands. And the great-great-great grandmother of the black woman who sat next to him was his ancestor’s slave, and the first of many generations of plantation cooks. Some things in the South you just can’t explain.

KAREN: Why do you think so many white southern writers are compelled to tell the stories of blacks?

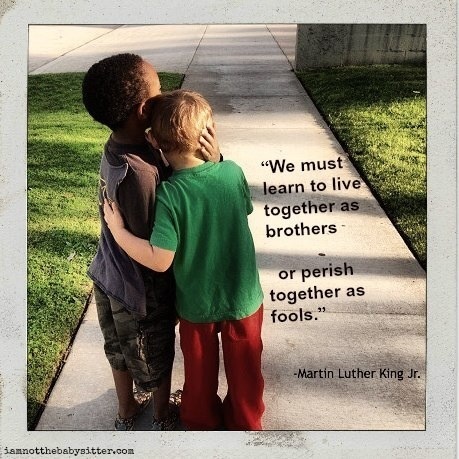

JONATHAN: I’m probably in the minority of white Southerners who believe this, but I think that black history fashions the white world as much, if not more, than the other way around. Robert Farris Thompson, who was a Yale art historian, said, “To be white in America is to be very black. If you don’t know how black you are, you don’t know how American you are.”

I’m fascinated with the ways in which I have been shaped, unconsciously, by a black America, even though their story has been mostly silenced, or made subservient to the white story. That’s what I told African Americans when I asked to interview them. I told them the history that I was given as a white man was bogus, embellished to make me feel good about myself. That I had a strong suspicion that their stories helped make me who I am. I believed that by discovering the texture of their lives and history, I would better understand the gaps in mine. I believe that’s what white Southern writers are attempting to do. We know there is a tear in the fabric of our narrative and it has to do with the physical closeness yet psychological distance we had with black folks. Most of us are very clumsy when we go about trying to knit-up that tear, but we are called to heal that wound nevertheless.

KAREN: That scene where Mistress Amanda demands that Ella give over her infant child is so disturbing, I felt such grief for Ella. Later I realized I had felt no sympathy for Miss Amanda, even though it was grief over losing her own daughter that propelled her to take Ella’s daughter from her. What did you fear most in writing that scene?

JONATHAN: There was so much happening in that scene. The mistress’s tragedy, the slave mother’s tragedy, the tragedy of the cook who is forced to look on, the ultimate tragedy of the child, the vital but fragile nature of motherhood, of belonging, of not having a say in the world that you are forced to inhabit. Everyone in that scene was a victim, each tugging at what sense of power and choice they could muster in their white, male dominated world. I wanted to keep the complexity, without it overwhelming the reader. More than anything, I didn’t want it to be a  simple villain-victim scene, where good and bad are clearly delineated. Like Simon Legree beating the good-hearted slave. Life is messy, and to some degree we are all making what we think are the best choices with the amount of power that we have. And those choices have an adverse impact, sometimes devastatingly so, on others. I did not want this scene, or the book, to be a simplistic morality play, with clear-cut, 2-dimensional characters. Unalloyed saints, victims and villains make for boring reading.

simple villain-victim scene, where good and bad are clearly delineated. Like Simon Legree beating the good-hearted slave. Life is messy, and to some degree we are all making what we think are the best choices with the amount of power that we have. And those choices have an adverse impact, sometimes devastatingly so, on others. I did not want this scene, or the book, to be a simplistic morality play, with clear-cut, 2-dimensional characters. Unalloyed saints, victims and villains make for boring reading.

KAREN: Issues of race have long been a point of advocacy for you. Who was that person, or what was that moment when you were first able to see others the way Polly talks to Granada about – the magic is in the seeing.

JONATHAN: I used to sell books door-to-door in college. I did it as a way of overcoming my shyness and a tendency to stutter. The sales company would send students to live on the other side of the country to make money or to starve. One of the publications they gave me to sell was the Ebony Pictorial History of Black America. This was in 1971 and it was the first complete history of African Americans to be mass marketed. That summer, in the face of threats from the local Klan, I asked over 1000 black families to allow me into their homes to give my sales pitch. I want to be clear. I did this for money, not from a sense of social justice. But something I had not bargained for happened to me.

So there I was, a Mississippi white boy, gathering up the whole family into the living room, showing them this amazing set of books, with stories not just of black athletes and musicians, but of generals and war heroes, scientists and doctors and politicians, inventors and business tycoons. What happened in those moments not only changed their lives, but it changed mine. The kids’ reactions, as well as the parents, was pure awe and wonderment. They had never heard of these people before. At first, I thought, “Well how illiterate! They don’t even know their own history!”

But then it hit me. Their history had been a victim to my history. Both couldn’t stand. These stories of heroism couldn’t exist in the same book as my stories of white superiority. I understood that they as well as I had been wounded by a one-sided, white-washed story. I understood to some degree, that the story I believe about myself determines not only the way I see myself, but the way I see others, the way I see the world. Those kids were deprived of their story to keep them invisible, to keep my story safe. In those moments of wonder, I actually “saw” them and I remember feeling what now I can only describe as a kind of grief, grieving the cost to our souls for having been sold a false narrative, a false sense of self. I learned that the repression of story can scar the soul. I learned that if you want to destroy a people, destroy their story. If you want to empower a people, give them the undisguised truth of their common story.

KAREN: Polly pares God down to one primary characteristic – God as Creator. “In the beginning, God created,” Polly says. “That’s all anybody ever needs to know about God.” There seems to be a lot of Native American theology packed into Polly’s view of God, including, as Gran Gran states later, that people need to be properly grieved into heaven. What informed you as you wrote this theology into Polly and Gran Gran?

JONATHAN: I tried to base as much of the spiritual aspect of Polly’s philosophy on the theology of a tribe in what today is Sierra Leon called the Temne. Many of Polly’s sayings come directly from them. The “feminine” is highly respected among the Temne, as well as the spirits of ancestors and the importance of memory. These aspects, as well as their prayerful relationship to nature, find many parallels among Native American theology. It was through these lenses that Polly understood and interpreted Christianity, and made it a source of empowerment for her people, rather than a tool of subjugation by the whites.

KAREN: Do you know the ending before you begin a book?

JONATHAN: I don’t know much of anything before I begin a book. Only a sense of mystery, something I am motivated to discover. They say to write what you know. I find that poor advice. What I know for sure is boring because there is no mystery left. Dry as dust. The only way I can keep energized, to spend 10 years writing a novel, is to find something I’m drawn to know, that keeps pulling me deeper and deeper into the mystery. When I’m surprised, then I can be sure the reader will be surprised too. If I know what’s coming, then the fun is over, for me and the reader.

KAREN: What are the most common misconceptions people make about you as a writer?

JONATHAN: I think the word “writer” itself is misleading. In the process of creating a novel, the time devoted to the actual motor skill of writing is minimal. Researching, daydreaming, tossing and turning in bed, running away to a different state, driving endless miles to get a feel for geography, interviewing hundreds of people, listening to recordings to catch dialect, these are what consume most of my time as a writer. Also, I don’t write because I have something to say. I write because there is something I want to know.

KAREN: Book clubs will love THE HEALING because of the complexities of the relationships that cross racial and age divides. Which of these women will you miss most?

JONATHAN: Polly Shine of course. Once she entered the book, she took over. She is the most powerful, mesmerizing, captivating, terrifying person I’ve ever come across. As you notice, I tell the story through Granada’s viewpoint. We learn about Polly by the impact she has on others. I could never enter her head. She would never allow me to write directly from her thoughts. She insisted, even with me as the author, on keeping a certain psychological distance. To know someone completely is in some degree, to control them through expectation. Polly insisted on being set free from that “wheel of predetermination.” She was always surprising me. I miss her because she is still a wonderful mystery, refusing to be solved, and yet bestowing on the reader a rock-solid certainty and confidence like none other.

KAREN: What are you working on next?

JONATHAN: I’m about 100 pages into my next “mystery”. I’m spending time with a couple of fascinating characters, two boys this go-round, one a black kid with albinism and the other a white gay kid. They are thrown together through circumstance. It’s the story again of belonging, which, come to think of it, seems to be a prevalent theme in all my writing. In my case I guess it’s true what they say about writers, no matter how many books they write, they tell the same story. I suppose that’s the overarching mystery that keeps me going, where does one truly belong? I do know the name of the book. The Last Safe Place. Which again, I suppose, testifies to this search for belonging.