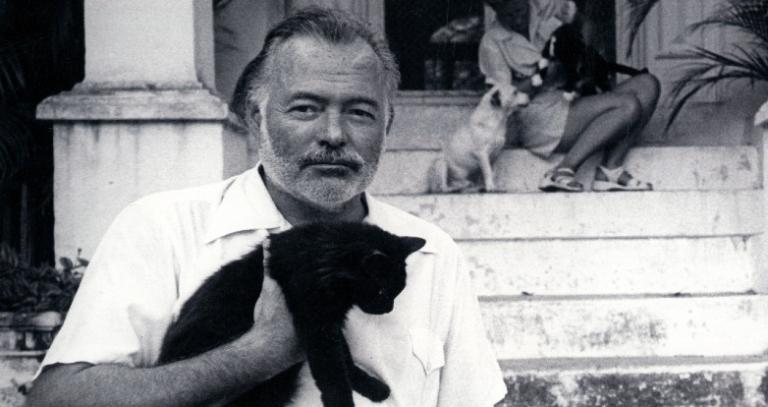

‘Hemingway’/PBS

Over three episodes and a total of six hours, PBS’ Hemingway, from Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, paints a fascinating and frequently unflattering portrait of a writer who ultimately drowned in his own Kool-Aid.

Ernest Hemingway was a swaggering, bullfighting-loving, big-game-hunting, womanizing, boozing boor who suffered head traumas, probably was mentally ill, and whose mother dressed him up as a girl. He married four women, had some, ahem, interesting sexual proclivities, and upsets people offended by traditionally masculine pursuits.

He was also one of the most celebrated writers of the 20th Century.

Hemingway airs Monday-Wednesday, April 5-7, from 8-10 p.m. ET/PT each night (check local listings). It can also be streamed online at PBS.org and bought on DVD.

PBS describes the series thus:

HEMINGWAY paints an intimate picture of the writer—who captured on paper the complexities of the human condition in spare and profound prose, and whose work remains deeply influential around the world—while also penetrating the myth of Hemingway the man’s man, to reveal a deeply troubled and ultimately tragic figure. The film also explores Hemingway’s limitations and biases as an artist.

I’m not a big devotee of Hemingway, but I do appreciate his muscular, straightforward writing style, learned as a Kansas City cub reporter (back when journalism was a craft, not a soapbox). It’s harder to write short than long, and Hemingway kept it terse.

Despite being accused these days of “toxic masculinity,” Hemingway is famed for writing excellent female characters, which probably irritates a certain subset of modern literary criticism.

He also died a Catholic, and considered himself one for most of his extravagantly imperfect life. From an extensive review of the subject in the University of Notre Dame’s Church Life Journal:

Hemingway was keenly aware of the ways in which his life did not conform to Church teaching—four marriages and three divorces would certainly suggest that he did not keep all of the rules of the Church. Nevertheless, all three of Hemingway’s children—Jack, Patrick, and Gregory— were brought up Catholic, and he always identified as such. This identification, however, did not spill over into his public, literary life. He explains his reticence about advertising his faith in an unpublished letter to a priest friend, Fr. Vincent Donovan:

I have always had more faith than intelligence or knowledge and I have never wanted to be known as a Catholic writer because I know the importance of setting an example—and I have never set a good example . . . Also I am a very dumb Catholic and I have so much faith that I hate to examine into it.” (December 1927, JFK Library, quoted in Stoneback, “In the Nominal Country,” 16).

What I took from Hemingway was that the writer came from a troubled family, had a profoundly screwed-up childhood, took advantage of his physical courage and good looks to get into dangerous places and woo women, suffered multiple serious head injuries, and ultimately committed suicide because of those, or mental illness, or booze, or all of the above.

While he was a gifted prose stylist, he doesn’t seem to have been capable of writing anything he hadn’t, to one degree or another, actually experienced. Much of his fiction tracks with his life (or perhaps it was the other way around).

People want to get close to authors and know more about them. IMHO, this is actually an attempt to connect with an embodiment of what they write, since you can’t shake hands with a fictional character. But, it’s inevitably disappointing and best avoided if possible.

But, Ernest Hemingway did have an interesting life, at least as compelling — if not more so — than those of his creations. He certainly misbehaved in many of the same ways.

Those who can’t separate the artist from the art may want to skip Hemingway, because it may cause them to skip Hemingway.

At the recent virtual winter edition of the biannual TV Critics Association Press Tour, Ken Burns commented:

He constructed a mask that was false, but even with that mask in place, the mask of the big-game hunter, et cetera, he was also questing for a kind of truth about things.

What’s so great in the great novels, The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms and For Whom the Bell Tolls and The Old Man and the Sea, and for me particularly, the short stories, of which there are 10, 12, 15 masterpieces of great, great art, he is getting out essential things about how human beings are. And that means that as he is confronting those demons, as he is going into those dark places … he is also coming back with news for us.

Those who can’t separate the artist from the art may want to skip Hemingway, because it may cause them to skip Hemingway. The miniseries didn’t particularly make me want to run out and read a bunch of his books, but it did inspire me to read one short story which is discussed at length in the documentary.

Published in 1927, Hills Like White Elephants (you can read the whole thing here) is set at a train station in Spain, where a young woman and an American man talk about the woman having an “operation,” which critics believe is an abortion.

The guy’s all for it; the girl, apparently less so. The ending is ambiguous. You can click here for a detailed examination of the story’s symbolism, which includes the theory that a beaded curtain refers to the rosary.

To paraphrase a line from Catholic writer Flannery O’Connor’s story A Good Man Is Hard to Find, “Hemingway might have been a good man, if it had been somebody there to remind him he was Catholic every minute of his life.”

I’ll leave all that to literary critics (as a writer, I can testify that a certain amount of thought goes into things, but sometimes you do it just because it seems like a good idea at the time). But, to have written a story about abortion in 1927, one that leaves the question unresolved, but which is intrinsically more sympathetic to the woman (the guy comes off as a jerk, and there’s an implication that this is not his first time at this particular rodeo), is not exactly what one would expect of an unrepentant misogynist.

Instead, it’s more like the product of a writer who has a clear-eyed view of human nature but can’t escape a sense of the sanctity of life — which is interesting if you know what was going on in Hemingway’s life at the time.

From a 2016 article in The Georgia Bulletin, the newspaper of the Archdiocese of Atlanta:

A reading of Hemingway’s correspondence from the early 1920s reveals a man who was frequently visiting Catholic churches and participating in Catholic rituals. He describes lighting votive candles for the intentions of his friends, and he names specific saints to whom he has prayed for intercession. He describes going to Mass, and at one point he states explicitly, “If I am anything I am a Catholic. … I cannot imagine taking any other religion seriously.”

To paraphrase a line from Catholic writer Flannery O’Connor’s story A Good Man Is Hard to Find, “Hemingway might have been a good man, if it had been somebody there to remind him he was Catholic every minute of his life.”

Image: PBS

Don’t miss a thing: Subscribe to all that I write at Authory.com/KateOHare