Nearly all Christians are Trinitarians because that is what their churches teach them. It was the same with me. What is the doctrine of the Trinity? It means God is one essence existing as (not in) three co-equal and co-eternal persons: the Father, the Son (Jesus), and the Holy Spirit. The initial reaction of most Christians when hearing this definition is, “well, yeah, there is the Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit. That’s all in the Bible.” Yes, but does the Bible teach that each is a person and equally God?

Nearly all Christians are Trinitarians because that is what their churches teach them. It was the same with me. What is the doctrine of the Trinity? It means God is one essence existing as (not in) three co-equal and co-eternal persons: the Father, the Son (Jesus), and the Holy Spirit. The initial reaction of most Christians when hearing this definition is, “well, yeah, there is the Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit. That’s all in the Bible.” Yes, but does the Bible teach that each is a person and equally God?

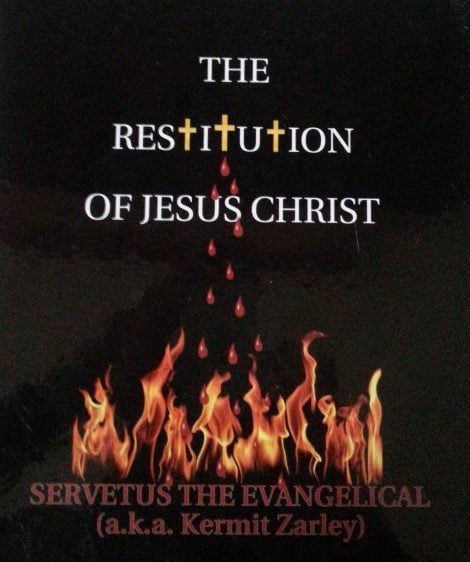

I was a Trinitarian Christian for twenty-two years. Then I questioned it, did extremely in-depth research, and changed to believing the Bible only says there is one God, who is the Father, so that Jesus is Lord and Savior, but not God. After 28 years of research and writing, I published a book on it entitled The Restitution of Jesus Christ (2008).

While I was researching this subject, I was surprised to learn that the doctrine of the Trinity that we Christians know about did not come into existence until the late fourth century. That is significant information. Why? I had always been told that if you didn’t believe in the doctrine of the Trinity, and thus that Jesus is God, you were not a Christian. That is what almost all churches have taught for hundreds of years. But did the churches of the first, second, and third centuries teach that? No!

Then, what about all of those Christians in those early centuries who had never heard of the doctrine of the Trinity? Were they not Christians because they did not believe in it? If so, that doesn’t seem quite fair, now, does it?

Not only that, the Catholic Church held its first so-called First Ecumenical Council in 325 at Nicaea. There, the 300+ bishops in attendance produced the Nicene Creed. It says Jesus is “very God of very God.” Then the last third of this creed pronounces multiple anathemas (condemnation to hell) upon all people who do not believe Jesus is very God of very God. They meant Jesus is just as much God as the Father is God. But amazingly, this creed says nothing about all the Christians who lived in the three prior centuries who were never taught that Jesus is just as much God as the Father is God. Were they, then, not Christians?

Christian teachers in the second and third centuries who wrote extant writings on theology are called “ante-Nicene church fathers.” They also are and were called “apologists.” This means they publicly defended the Christian Faith. All of those apologists believed God the Father was supremely God and that Jesus also was God but that his divinity or deity was of a lesser sort than that of God the Father. In theology, this is called “essential subordination.” That is, Jesus was subordinate to the Father regarding their essence, their very beings. I call this teaching “big God, little God.” In my intense investigation, I came to believe that neither it nor the doctrine of the Trinity are biblical teachings. But what about the Holy Spirit?

Until the late 4th century, the Catholic Church had not made any determination about the nature of the Holy Spirit, much less whether God is triune. During the 3rd century, church father Tertullian had put forth legal language, which included “trinity” (L. trinitas),[1] and the Church later used it to forge its doctrine of the nature of God and Jesus’ identity. But this former lawyer was no Trinitarian by modern standards.

Minutes were not taken at the Nicene Council. Some historians claim that this was purposeful. Regardless, there is no evidence in patristic writings that the Nicene Council ever discussed the nature of the Holy Spirit or that whether or not God is three persons. Neither is there any such mention in the Nicene Creed. Like the Apostles’ Creed, it only says, “We believe … in the Holy Spirit.”

The chief purpose for which the Nicene Council was convened was to settle a dispute that had arisen between Bishop Alexander, of Alexandria, Egypt, and Arius, a presbyter in Alexander’s holy see. Both men claimed to believe that Jesus was God. Their dispute was about whether Jesus preexisted eternally as the Logos-Son (Alexander) or that God the Father created the Logos-Son prior to creation (Arius), in which case Jesus did not preexist eternally. So, this dispute was about whether (1) Jesus was just as much God as the Father was (Alexander) or (2) Jesus’ status as God was less than the Father’s.

Thus, church historian J.N.D. Kelly observes that at the time of the Nicene Council, “the Holy Spirit … had not yet become the subject of disputes.”[2] Indeed, I say in my book, The Restitution of Jesus Christ (p. 50), “Interestingly, the Nicene Creed portrays only a Binitarian faith. The subject of the Holy Spirit was not even discussed by the Council. Throughout the 2nd and 3rd centuries, there existed no consensus of opinion among church fathers on the nature of the Holy Spirit. Some thought the Holy Spirit (Spirit of God) was merely an impersonal power or attribute of God. Others ascribed personality to the Holy Spirit. A few refused to speculate about the matter, refusing to go beyond the express declarations of Scripture. P. Schaff explains, ‘the doctrine of the Holy Spirit was far less developed, and until the middle of the fourth century was never a subject of special controversy.’ At the time of the Nicene Council, the Church clearly had not developed what later became the doctrine of the Trinity.”

Soon after the Nicene Council, Athanasius succeeded Bishop Alexander. For decades following, he was the leading proponent of Nicene orthodoxy. R.P.C. Hanson, who is the preeminent authority on the development of the church doctrine of God in the 4th century, informs, “It was Athanasius of Alexandria who first faced squarely the subject of the Holy Spirit … in 359 or 360.” [3] My book (p. 520) states, “Nothing changed for the decades after the Nicene Creed. Thus, R.P.C. Hanson (p. 741) also relates, ‘When we examine the creeds and confessions of faith which were so plentifully produced between the years 325 and 360, we gain the overwhelming impression that no school of thought during that period was particularly interested in the Holy Spirit.’ A few fathers only argued that the Holy Spirit is a distinct hypostasis essentially subordinate to the both the Father and the Son, thus rending the Holy Spirit unequal with both.”

J.N.D. Kelly informs, “When the council of Constantinople met in 381, one of its express objects was to bring the Church’s teaching about the Holy Spirit into line with what it believed about the Son.”[4] Kelly means that until this time the Church had never officially proclaimed that the Holy Spirit is co-equal in divinity with Jesus Christ the Son. Kelly therefore adds that at Constantinople, the Church “proceeded to assert the full deity and consubstantiality [same essence] of the Holy Spirit, and His existence as a separate hypostasis,” just as it had done at Nicaea concerning the identity of Jesus and his relationship to the Father.[5]

Thus, the Council of Constantinople, designated the Second Ecumenical Council, produced its own creed. It substantially repeats the Nicene Creed and adds the following about the Holy Spirit: “We believe … in the Holy Spirit, the Lord and life-giver, Who proceeds from the Father, Who with the Father and the Son is together worshipped and together glorified.” Interestingly, this creed does not even mention the word “trinity” nor precisely set forth a doctrine of the trinity. Yet three church fathers, called “the three Cappadocians,” had previously produced treatises upon which this creed was based, and those documents fully explain what was to become the traditional doctrine of the trinity—God is one essence subsisting as three Persons: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

In conclusion, this church doctrine of the Trinity, which has been believed by nearly all Christians for over 1,500 years to the present time, did not obtain at the Council of Nicea, in 325, but at the Council of Constantinople, in 381. This history–that it was 3o0 years after the beginning of Christianity that the Catholic Church decided Jesus is just as much God as the Father is, and that it took 350 years for the Church to decide that God is three co-equal and co-eternal persons–should be very disturbing to Trinitarians as it was to me. This is especially so in light of the biblical exhortation, “contend for the faith that was once for all entrusted to the saints” (Jude 3). That is, DON’T CHANGE THE FAITH. That is what church fathers did in deciding that God is three persons, and they did it 350 years after Christianity began.

So, what is the Christian Faith? What is the gospel? It is that the one God sent Jesus to die for our sins. God then raised him from the dead. We need to believe this and make Jesus Lord of our lives. In other words, accept Jesus as your personal Lord and Savior. That’s the gospel. Trinity, deity of Christ; that has nothing to do with the gospel of salvation. Church fathers were dead wrong to include that in the gospel that saves.

The following citations are from the Wikipedia article entitled “NonTrinitarianism”:

The New Catholic Encyclopedia says, “The doctrine of the Holy Trinity is not taught [explicitly] in the [Old Testament]”, “The formulation ‘one God in three Persons’ was not solidly established [by a council]…prior to the end of the 4th century”. Similarly, Encyclopedia Encarta states: “The doctrine is not taught explicitly in the New Testament, where the word God almost invariably refers to the Father. […] The term trinitas was first used in the 2nd century, by the Latin theologian Tertullian, but the concept was developed in the course of the debates on the nature of Christ […]. In the 4th century, the doctrine was finally formulated.”[6] Encyclopædia Britannica says: “Neither the word Trinity nor the explicit doctrine appears in the New Testament, nor did Jesus and his followers intend to contradict the Shema in the Old Testament: “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God is one Lord” (Deuteronomy 6:4). […] The doctrine developed gradually over several centuries and through many controversies. […] by the end of the 4th century, under the leadership of Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus (the Cappadocian Fathers), the doctrine of the Trinity took substantially the form it has maintained ever since.”[7]

So, why do most people, including many scholars, erroneously think the traditional doctrine of the Trinity was formulated at the Nicene Council, in 325? It’s due to church practice. Parishioners of mainline church denominations often recite at Sunday church services what church leaders represent to them as the Nicene Creed. But, in fact, what they recite is a revision of that creed which was undertaken at the Council of Constantinople, in 381, and correctly called the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed.

[1] Bishop Theophilus, an earlier church father, was the first to apply the word trinity (Gr. trias) to God.

[2] J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Creeds, 3rd ed. (Essex, England: Longman, 1972), 340.

[3] R.P.C. Hanson, The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God: The Arian Controversy, 318-381 (London: T & T Clark, 1988), 748-49.

[4] Kelly, Early Christian Creeds, 340.

[5] Kelly, Early Christian Creeds, 341.

[6] John Macquarrie, “Trinity,” Microsoft Encarta Reference Library 2005. © 1993-2004 Microsoft Corporation. Retrieved in March 31, 2008.

[7] “Trinity,” Encyclopedia Britannica 2004 Ultimate Reference Suite DVD. Retrieved in March 31, 2008.

………………

To see a list of titles of 130+ posts (2-3 pages) that are about Jesus not being God in the Bible, with a few about God not being a Trinity, at Kermit Zarley Blog click “Chistology” in the header bar. Most are condensations of my book, The Restitution of Jesus Christ. See my website servetustheevangelical.com, which is all about this book, with reviews, etc. Learn about my books and purchase them at kermitzarley.com.