My mother has her outlets here and there, but she has shaped her entire identity around her role as wife and mother in pursuing the ideal of Christian Patriarchy and Quiverfull. It is who she is. She believes that it is her god-given role to spend her life raising us, homeschooling us, shaping us, so that we can go out into the world and retake it for Christ, and that is what she has done for two and a half decades. Being a mother is who she is.

And so, when I disappoint my mother, I feel guilt. When I go in a direction different from what she wants for me, I feel like I invalidate her life, because, motherhood was and is her life. She sacrificed for us children in numerous ways, often doing things she didn’t want to do because she believed that this was what she was meant to be. She made her life about us. The guilt I feel when I disappoint her, after all she sacrificed to raise me, is palpable. And it’s not easy to shake, either. I feel like she gave up everything – everything – for me, and I threw it all back in her face.

Interestingly enough, in previous historical eras it wasn’t like this. Women were mothers, yes, but that was never their entire identity. As historian Julie Grant explains, “For sixteenth- and seventeenth-century colonial American women, child rearing was only one of a multitude of tasks shared by neighbors and kin.” Even as they raised large numbers of children, women worked in shops alongside their husbands, in the fields on the family farm, and in the home sewing, preparing food, washing, and caring for the sick. Even when the nineteenth century separated work from the home for many families, sending the father off to the office or the factory, the wife did far more than simply raise children. Many women took in extra work, supplementing the family income with laundry or sewing. Others threw themselves into reform issues, working with other women to close saloons and improve conditions in the slums. For those who did neither, simply running a house in the nineteenth century, with no running water or electricity, remained an absorbing task.

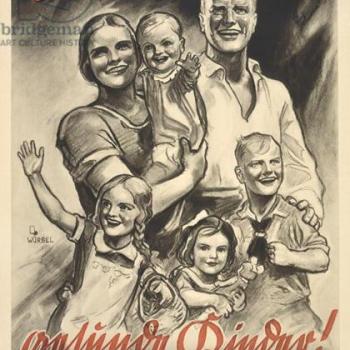

During this whole time children fit into their parents lives rather than the parents shaping their lives around the children. Children played on their own while their mothers churned butter and made soap, or sat beside their mothers and helped make paper flowers to sell. Rather than completely disrupting them, the child fit neatly into his parents’ lives. This changed with the development of the child centered family. The child centered family had its beginnings among the middle class in the nineteenth century and from there grew and spread to the rest of society. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, children were increasingly barred from the workforce and school attendance became compulsory. Families had fewer children but at the same time invested more into raising them. When a growing number of middle class women moved to the suburbs in the 1950s and made being a wife and mother the whole of their identities, this new phenomenon of the child centered family, where the parents, and especially the mothers, remade their entire lives around their children and their children’s needs, hit its zenith.

Second wave feminism emerged in reaction to the suffocation many women felt in the 1950s as they found that making motherhood the sole of their identities was not all that they were told it would be. Sometimes, in their zeal to fix the problems of the fifties, second wave feminists went too far and treated motherhood and housework as the problem. Others, though, did not see a contradiction between motherhood and feminism. Some argued that housework and motherhood should be seen as labor and valued as an economic contribution. Others embraced “woman power” and saw women’s ability to procreate as central to their beings. Still others embraced breastfeeding and midwifery, seeking to dethrone male child-rearing experts and elevate women’s knowledge and intuition in pregnancy and child rearing. Today’s third wave feminists generally embrace female choice, whether that choice is to be a stay at home mother, to be a childless career woman, or to have both a job and children. Feminism is simultaneously about expanding women’s choices and reminding women not to sublimate themselves and their own fulfillment to the expectations that surround them.

But how does this relate to how I started this post, you may ask? Well, Shadowspring’s mother put herself and her personal needs ahead of everything else to the extent that she made her own children feel unwanted. In contrast, my mother, just like many other mothers who embrace the Quiverfull idea, sublimated herself and her personal needs to the extent that her entire identity revolved around her role as wife and mother. Interestingly, both of these extremes are particularly modern, rather than historical, problems. And as should be apparent by now, neither extreme is healthy for either the children, or, I would argue, the mother. No mother should embrace her own fulfillment to the extent that she forgets about or resents her children, and no mother should embrace her own children to the extent that she forgets about her own fulfillment and personhood.

Thus I would argue that to achieve any sort of healthy balance any woman who chooses to have children needs to throw herself into both motherhood and feminism – embracing her children and their needs, and, at the same time, herself and her needs. These two are by no means contradictory, either today or in the past. And that is why I confidently declare that I am a feminist and a mother, and I take pride in both.