Matt Walsh recently published an article urging early marriage.

I was 24 when we met and got engaged and 25 when we tied the knot. That would make us pretty run of the mill by our grandparents’ standards, but not anymore. These days we’re practically a Ripley’s Believe It Or Not exhibit.

People are downright befuddled to come across a 20-something with a wedding ring, much less a couple of carseats in the back of the sedan.

There’s a good reason for their shocked amazement. Indeed, young families are a dying breed.

None of this reflects the reality I live in at all. I don’t know anyone who is befuddled by a twenty-something with a wedding ring, and I’m saying that as a twenty-something with a wedding ring. I don’t know where Walsh lives, but here in this midwestern college town young families and married twenty-somethings and twenty-somethings with children are not abnormal at all.

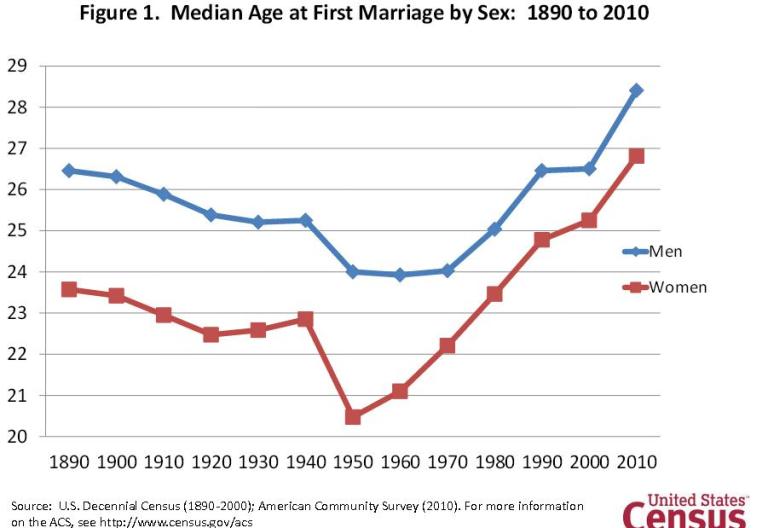

Today, the median age at first marriage for a man is 28.5. Yes, Walsh married three years younger than this, but so did lots of men—that’s how this sort of statistic works. If you line up all the male ages at first marriage, the middle one will be 28.5. That means half of men who marry do so before they are 28.5. That’s how medians work. Furthermore, male age at first marriage has historically been in the late twenties. Walsh’s grandparents were actually an abnormality—the 1950s saw historically low marriage rates not seen in the United States either before or since.

It seems every week we get a new report illustrating what we already know: young people aren’t getting married. Millennials are delaying marriage longer than any generation before us, and according to some studies, more than 25 percent of us will never take the plunge at all.

We are, without a doubt, the most marriage-averse group in human history.

You know, it might well help to look at the facts.

[second image eaten by the internet]

But what about before 1890? We don’t have census data for that period, but that doesn’t mean we can’t work out what was going on. It turns out that American history has been characterized by large swings in average age at first marriage. See this from the Journal of Southern History, for instance:

Although studies are few and subject to possible biases, most scholars agree that the ready availability of inexpensive land in colonial America made marriage feasible at an early age. As a result, marriages occurred several years earlier, on average, in colonial America than in Europe, and much higher proportions of the population eventually married. Community-based studies suggest an average age at marriage of about 20 years for women in the early colonial period and about 26 for men. As population densities increased and land prices rose in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, American couples delayed marriage, and a higher proportion remained permanently unmarried. The published census figures for 1890, which are the earliest that permit estimates of age at marriage, reveal that the mean age at marriage was 23.8 for white women and 27.8 for white men—little different from those ages in England.

And this from History of the Family:

Between 1800 and the present there have been long cycles in nuptiality. Since about 1800, female age at first marriage rose from relatively low levels to a peak around 1900. Thereupon a gradual decline commenced with a trough being reached about 1960 at the height of the baby boom. There then began another, and rapid, upswing in female marriage age. Proportions never married at ages 45-54 replicated these cycles with a lag of about 20-30 years. Since 1880 (when comprehensive census data became available), male nuptiality patterns have generally paralleled those of women.

There are a couple of things to note here.

First, marriage rates are often affected by the availability of resources. More resources mean more people marry and have children. Fewer resources mean more people delay marriage and having children. This is common sense—it takes resources to buy a house, raise children, and otherwise set up a household. When resources are scare, many young adults live with their parents longer or scrape by on their own on a standard of living they would not be comfortable having children on.

Second, note that even during the colonial era, when marriage rates were high, men married at age 26 on average. We have this idea in our mind of all sorts of teenage marriages, but this idea was not the reality for most colonists. Now yes, the average colonial woman married at 20, which means that many women married at 18 or 19 or younger. But many others didn’t. And while most women did marry, they did so because they had to—marriage was the only path to economic security. Today it’s not. Today women get to choose whether they want to marry.

Third, the 1950s were in many ways an abnormality. In fact, the median age of first marriage for a man in the United States hit its historical low in the 1950s, when the GI Bill and Levittowns made it especially easy to set up a household and family unit. For women, the median age of first marriage fell back to 20, the age it had been during the colonial period. If we measure our own time against the 1950s, of course it looks like what we’re experiencing today is unprecedented. If we look back longer, we find that it is normal for the United States to have large swings in the average age of first marriage. It is actually the marriage rates of the 1950s that were unprecedented.

In the colonial period, marriage rates were high and the average age at first marriage was low because resources were plentiful and establishing a household and family was inexpensive. The same was true in the 1950s. The same is not true today. There are a variety of very real reasons young people today are delaying marriage longer than the last few generations, but Walsh seems unconcerned with these.

The real story here is the rise of the median female age at first marriage, which is up from 23 in 1980 to 26 today. The increase is only three years, but it is significant in that it is no demographic accident. Women are more likely to have careers today, and to want to be more established before marrying—and before having children (the average age of a first-time mother is now 25, up from 21 in 1970). I don’t see this as a problem, but those who do would be better off examining the reasons women are marrying and having children later than previous generations than simply urging women to marry and procreate earlier.

Back to Walsh:

Look, I’ve been young and single. In fact, I’ve been more single than many of you, as I lived completely on my own — no roommates or live-in girlfriends — for the first five years of my twenties. And I’ve also been young and married with kids and responsibilities. If I could choose between the two, I’d take young and married every time, without a doubt.

The key word there is choice. I mean yes, I’d absolutely choose being married to Sean and raising my two children over being single and having no children. But then, I did choose it. Not everyone is like me. Some people would absolutely choose being single and having no children over being married with children, and I would much rather them remain as they are than be saddled with things they do not want. Especially children. No one who doesn’t want children should be pushed to have children—ever.

You won’t hear this from very many people anymore, but this is my advice: get married young. Have kids. Don’t be scared of growing up.

“Get married” does not equal “growing up.” No really! It doesn’t! You do not have to get married to be a grownup! Also, I hate to pop Walsh’s bubble, but it seems like all I hear are calls for young people to marry. Walsh may think saying this makes him special, but it actually makes him the norm among conservatives. Marry young! they say. All of your problems will be solved!

Most people are supposed to venture out into the world and start families while they are still young and full of life and energy.

Most people. I didn’t say all. I didn’t say every. I didn’t say there aren’t exceptions or that people don’t have different vocations and callings in life. I said most. As a fundamental, general principle, human beings shouldn’t wait until they’re 35 or 40 to start a family. That’s what our twenties are for.

We’re “supposed to” get married and have children young? We “shouldn’t” wait until we’re 35 or 40? That’s what our twenties “are for”?

Says who?

If Walsh wants to claim a Biblical mandate, he’s free to do so. If he wants to claim we have a societal obligation to marry and have children young he’s welcome to, but he’d have to actually make that case. All Walsh offers are completely unsupported claims, telling people what they should and should not do just because, and in doing so he completely ignores the myriad of reasons people are not marrying younger—and the fact that the average age of marriage has historically varied widely—and the fact that only 15% of childbearing women have their first child after age 35.

Next, Walsh makes his case for early marriage. It’s worth remembering that Walsh himself has only been married for three years. Here are Walsh’s points, with my paraphrasing:

1) You don’t need money to get married.

2) You aren’t your parents.

3) Marriage is about experiencing life with your spouse by your side.

4) Youth is a gift.

5) Family life is edifying.

6) You don’t have to wait for ‘The One.’

7) Biology is a thing.

8) It’ll be the best adventure of your life.

I’m not going to get into his arguments in detail, but they boil down to: (1) Kids don’t cost anything; (2) you shouldn’t worry about having your parents’ marriage problems yourself; (3) marriage miraculously makes your partner extra special to you; (4) you should give your young years to a spouse rather than to your boss; (5) having to sacrifice will make you a better person; (6) rather than being picky you should just pick someone and hold on; (7) women’s ovaries shrivel up after their twenties; and (8) real adventure comes from marriage rather than hair dye or whatever else kids these days do.

Age at first marriage has traditionally correlated with the availability of resources needed to set up a household and raise a family. Walsh completely blows that off by stating (historically, I might add) that you don’t need money to get married. He also states that children don’t cost anything, a claim I find absolutely gobsmacking.

Walsh claims children are not expensive to raise. I should ask him to go to my children’s daycare center and ask them to return the $50,000 and counting I have paid them over the past few years. Then there is health insurance, diapers, food, and clothing. When both of my children were in daycare, before my oldest started kindergarten this fall, between daycare and health insurance alone my children cost me close to $25,000 per year. Sure, I could have stayed home with my children rather than putting them in daycare, but that would have meant sacrificing my income—in other words, whether I stay at home or put my children in daycare, we’re still talking about tens of thousands of dollars. Yes, we make it work, and so do plenty of other families—but telling people children don’t cost anything does everyone a serious disfavor.

But it’s not just children that cost money. Walsh acts as though those young people who aren’t marrying all have jobs and apartments and all they need to do is get married and move with each other. Sometimes this is the case, but it isn’t always. Walsh appears to be unaware of the fact that many young people today have moved back in with their parents because they cannot afford their own places, or that many Millennials cannot find jobs, or are stuck in minimum wage jobs that barely cover rent. And of those Millennials who do have their own apartments, they frequently have several roommates to make rent, so Walsh can’t suggest that marrying and moving in together will cut costs, as I have heard people argue before.

This article could have been so different. Walsh could have mentioned that marriage rates are going up, and then speculated as to why. He could have then asked for feedback from readers to help him understand the reasons people are marrying later. Finally, he could have stated that he has personally found young marriage rewarding, and he could have given the reasons for this. He could also have considered ways we could change our social institutions to make it easier for those who wish to marry to afford to do so. Instead, Walsh speaks of declining marriage rates as though civilization is about to end and then commands his readers to marry young, arguing with little nuance that his own personal life choices are best for everyone.

And perhaps more than anything else in this piece, I’m troubled by the insistence on equating “marriage” and “family.” We really should be moving beyond this by now. I have several friends who are not married and have never been married, but are raising children nonetheless. They absolutely consider themselves families, but Walsh likely would not. He would rather reduce the term “family” to heterosexual married couples with children, and then try to push everyone into that mold. Look, I’m glad it works for Walsh! It works for me, too. But I have enough maturity to recognize that other people are not me.