Last week, Rand Paul had this to say on vaccines:

The state doesn’t own your children. Parents own the children.

I’m becoming very very tired of this dichotomy. For individuals like Ron Paul—or Michael Farris—if parents do not “own” their children, the state “owns” them. Is it so hard to consider that perhaps children are not property? Is it so difficult to imagine that children could “own” themselves?

And are those who advocate for universal vaccination are not arguing that the state “owns” the kids? No, they’re not. Check out the language used here:

In Mississippi, a state Supreme Court judge did not mince words in 1979 when he overturned a short-lived exception granted to parents ideologically opposed to immunizations: “To the extent that [vaccines] may conflict with the religious belief of a parent, however sincerely entertained, the interests of the schoolchildren must prevail.”

Is it that hard to understand that children have interests of their own? I am a parent myself, and yet I dislike the framework of parental rights, preferring instead to think in terms of parental responsibilities. Besides, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which is often painted as a boogeyman by conservatives, states that the child has the right to “be cared for by his or her parents.” In other words, understanding that children have their own interests—and, yes, rights—is in no way inconsistent with a belief that children should be cared for by their parents.

But as long as we’re talking about the measles outbreak and vaccines, I might as well take a moment to go over some facts. Children have an interest in having adequate healthcare and not dying from preventable diseases. Parents are responsible for protecting that interest as best they can, but matters of public health are also something we delegate to the state. The state has a responsibility to protect the interests of not only children but all of its citizens. Preventing disease and stopping epidemics is part of this.

A recent article presenting a timeline of measles states the following:

1963: The first measles vaccines were licensed in the U.S.

Measles’ lethality had dropped by the 1960s, thanks to improved treatment and nutrition, with less than one death reported for every 1,000 cases. But before the vaccines, millions of American children were infected every year, and many developed serious side effects: An annual average of 48,000 measles patients required hospitalization, with 400 to 500 deaths per year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The most serious side effects included pneumonia and encephalitis – swelling of the brain. Hearing loss from measles-related ear infections was also common.

Measles vaccines slashed those infection rates. Over several decades, the vaccines were were bundled with vaccines for mumps and rubella into a booster shot parents now know as the MMR. State legislatures began mandating vaccination for school students in the 1960s and 1970s, and eventually every state and the District of Columbia adopted such laws, with some exemptions for medical, philosophical or religious reasons.

1989-91: A measles outbreak in the U.S. brought 55,000 cases, 11,000 hospitalizations and 123 deaths. The virus infected some vaccinated patients in the U.S., leading experts to begin recommending a second dose of MMR.

For the next decade, measles infection rates grew so low that, by 2000, measles was declared effectively eliminated in the U.S. But the virus remained prevalent around the world.

Here’s a graph that shows the rate of measles infection in the U.S.:

Here’s a graph that zooms in and looks at the recent past:

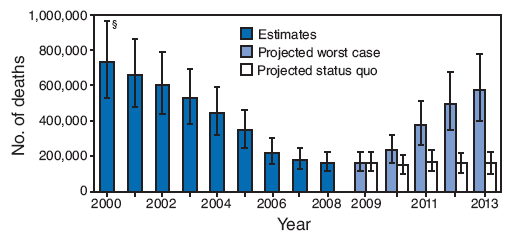

And finally, here’s a graph that shows global measles deaths:

According to the World Health Organization:

- Measles is one of the leading causes of death among young children even though a safe and cost-effective vaccine is available.

- In 2013, there were 145 700 measles deaths globally – about 400 deaths every day or 16 deaths every hour.

- Measles vaccination resulted in a 75% drop in measles deaths between 2000 and 2013 worldwide.

- In 2013, about 84% of the world’s children received one dose of measles vaccine by their first birthday through routine health services – up from 73% in 2000.

- During 2000-2013, measles vaccination prevented an estimated 15.6 million deaths making measles vaccine one of the best buys in public health.

Frankly, the prevalence of anti-vaxxing in the U.S. in light of these facts is astounding.

I want to finish with one more point. And as a blogger at the Economist pointed out, even if we did believe parents “own” their children—and that children are property—that would not put an end to state interest.

When Mr Paul says “the state doesn’t own your children”, he seems to be saying that the state has no standing to override or undermine the authority of parents by telling them what to do with their kids. The language of ownership is unfortunate. We don’t own our children. Even if we did, however, it wouldn’t follow that ownership implies that the state can’t justifiably tell us what to do with our property. I literally own my dog. He is chattel. (Sorry, Winston!) I can have him euthanised pretty well whenever I like. (Don’t worry, Winston!) Nevertheless, I am required by law to have him vaccinated for rabies, and rightly so. This does not imply that the state owns my dog. Property in the real world always comes attached with all sort of liabilities that smooth the tensions between private control and public welfare.

This isn’t the kind of thing where a person’s actions only affect themselves. In this case, a parent’s decision not to have their child vaccinated affects their child in addition to them, but it also affects the other children around them, and the general public—especially children who are immunocompromised or too young to be vaccinated.

This isn’t a question of whether the parents or the state own a child. That is the wrong question to ask entirely. This is a question of how best to protect children’s interests.