I was reading the abstract of a 1986 article on declining SAT scores when a sentence brought me up short. “In particular, a large part of the recent SAT score decline was caused by the large families of the post-war baby boom.” What? Why would large families contribute to falling SAT scores? I scanned the text.

Large families, female-headed families and a less educated populace reduce SAT scores.

There it was again! And further down:

The three major contributors to the predicted change in SAT scores in the 1970s are the rise in the number of siblings, which yields a 40 point decline, the rise in female-headed families, for a 9 point decrease, and the rise in the college educated fraction of the population for a 22 point increase in SAT scores.

On a rational level, I get what’s going on here. The more children a family has the fewer resources (time, money) they have to invest in each individual child. Parents with only one child can focus on that child’s schooling, homework, and performance in a way that parents with four children can’t. But on an emotional level, this brought up an outpouring of memories from my childhood.

I grew up in an exceptionally large family. My parents always said money wasn’t an issue, because the best gift parents could give their children was another child. Kids in smaller families might get more toys, they said, but they were the ones who were missing out, in the end. We were the lucky ones. The decreased amount of attention and input each individual child would of necessity receive was never discussed, and I most certainly did not know, at the time, that family size negatively affected children’s academic performance.

But check out this article from earlier this year:

Every kid from a small family has probably felt sorry for themselves at one time or another for not having loads of brother and sisters. From the outside looking in, there’s a lot to envy about families that have enough kids to field their own baseball game, produce complex harmonies a la “The Sound of Music,” or put on a play without casting stuffed animals in major roles.

But a new study shows there are convincing reasons not to romanticize large families. A recently published paper from three economists that looks at 26 years of data on parents and children suggests that with every additional kid born, the other siblings are more likely to suffer from lower cognitive abilities and more behavioral issues, and have worse outcomes later in life.

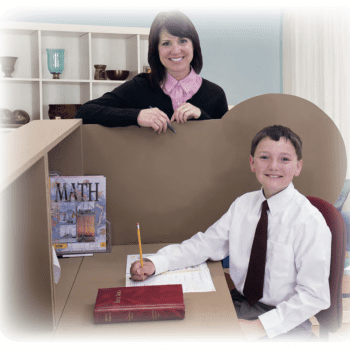

I am absolutely fascinated. I was homeschooled, and heavily involved in our local Christian homeschool community, which was plugged into national trends. One thing that appears to transcend the various differences in theology between popular Christian homeschool leaders is the idea that parents should strive to have large numbers of children. This is often referred to as the “quiverfull” movement, and many a couple who initially intended to have a typically sized family has gone on to have six, eight, ten, or more children under the influence of these teachings. And guess what isn’t mentioned? Any of these negative results.

I’m not saying people shouldn’t have big families. What I am saying is that people who choose to have large families need to go into it with their eyes open. They need to know that having a larger number of children increases the risk that the children will have behavior issues, and reduces children’s academic performance. They need to know these things so that they can work against these problems from the outset, spending time with their children, investing in their children’s work at school, and so forth. It is irresponsible to encourage people to have large numbers of children without letting them know that children in large families suffer certain disadvantages.

Yes, we had enough people to have our own baseball games—and we did just that in the field behind our house—and while we were never collectively musical, we put on loads of in-house plays and never once thought of casting stuffed animals in major roles. Do people seriously do that? If so, I honestly had no idea! Our plays sported a rousing cast of very human characters. But for all that, the time my parents had to spend with us, especially individually, was divided into increasingly smaller slices, and the amount of time my mother had to focus on each individual child’s homeschooling decreased as time went on and the seats in our fifteen passenger van filled up.

During the decade or so since leaving home, I’ve met an increasing number of individuals—both children and adults—who either were only children and loved it, or wish they’d been only children. I’ve also met only children who wish they’d had siblings, of course (and kids with many siblings who wish they’d had fewer). The very premise alluded to in the article about recent research—that every kid from a small family sometimes feels sorry for themselves—isn’t in my experience as true as I was certainly lead to believe it was as a child.

While we can’t dictate the “right” number of children couples should have (and shouldn’t try), there are some things we can say with a fair degree of confidence. First, children have a deep need for love and attention from their parents (or other caregivers), especially when they are younger. And second, the more children you have, the less time you’ll have to focus on any one child’s academic (and social) development. These are things parents need to know from the outset, whether they have two children or eight.

And yes, the baby boom really did drive down national SAT scores.