I recently began reading Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea cycle. I’ve read her other work before, but I’d never picked up her Earthsea books, which are fantasy, rather than her more typical science fiction fare. I read her first book, A Wizard of Earthsea, about a boy named Ged, who becomes a wizard. Ged is described as having red-brown skin.

After finishing this book I moved on to the next in the series, which focused on Tenar, a young girl living in the Kargad lands. The people of Kargad have light skin. Tenar was typical in this respect, and is described as having black hair.

This picture was on the front of my copy of Tombs of Atuan:

It’s a gorgeous piece of artwork. I immediately assumed the girl in the picture was Tenar, and I figured the guy would be introduced later on. But that’s not exactly what happened. The man on the cover never entered the book, but Ged did. I did a double take. That man on the cover—that was supposed to be Ged?

Now yes, in the picture above, the man’s skin is darker than Tenar’s. But would you describe his skin as “red-brown”? I wouldn’t. Tanned, yes. Red-brown, no.

I should have seen it, because my copy of Wizard of Earthsea had an afterward written by Ursula Le Guin, and I had read it. In this afterward, Le Guin wrote that her decision to make Ged a person of color was intentional—that when she wrote the book in 1968, there were few fantasy characters of color, and she wanted to change that.

Le Guin even notes her frustration with illustrators:

His people, the Archipelagans, are various shades of copper and brown, shading into black in the South and East Reaches. The light-skinned people among them have far-northern or Kargish ancestors. The Kargish raiders in the first chapter are white. Serret, who both as a girl and woman betrays Ged [in Wizard of Earthsea], is white. Ged is copper-brown and his friend Vetch is black. I was bucking the racist tradition, “making a statement”—but I made it quietly, and it went almost unnoticed.

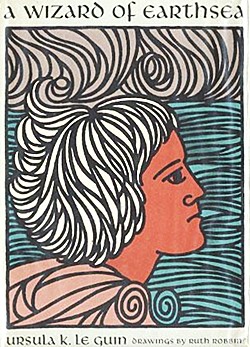

Alas, I had no power, at the time, to combat the flat refusal of many cover departments to put people of color on a book jacket. So, through many later, lily-white Geds, Ruth Robbins’ painting for the first edition—the fine, strong profile of a young man with copper-brown skin—was, to me, the book’s true cover.

I read that—I did—and still, when I picked up Tombs of Atuan, I didn’t realize that was Ged on the cover. At that point, in my defense, I hadn’t realized that Ged was a recurring character. The first Earthsea book was about Ged; the second was about Tenar. That was what I knew. Who knew what the third might be about?

After realizing that that tanned white man on the cover of the book was meant to be Ged, I started googling, curious about other depictions. I learned that in the early 2000s, a miniseries was made based on Earthsea. Here—I kid you not—is Ged (with, I assume, Tenar):

The problem posed by this miniseries—which cast a white actor as Ged—was so big that Le Guin herself felt the need to address it in an article titled “A Whitewashed Earthsea.”

On Tuesday night, the Sci Fi Channel aired its final installment of Legend of Earthsea, the miniseries based—loosely, as it turns out—on my Earthsea books. The books, A Wizard of Earthseaand The Tombs of Atuan, which were published more than 30 years ago, are about two young people finding out what their power, their freedom, and their responsibilities are. I don’t know what the film is about. It’s full of scenes from the story, arranged differently, in an entirely different plot, so that they make no sense. My protagonist is Ged, a boy with red-brown skin. In the film, he’s a petulant white kid. Readers who’ve been wondering why I “let them change the story” may find some answers here.

When I sold the rights to Earthsea a few years ago, my contract gave me the standard status of “consultant”—which means whatever the producers want it to mean, almost always little or nothing. My agency could not improve this clause. But the purchasers talked as though they genuinely meant to respect the books and to ask for my input when planning the film.

As it turns out, they didn’t. They didn’t include Le Guin in the decision making in almost any capacity. And so, well, the whitewashing happened. And more, apparently. I haven’t seen the miniseries, but I am left with no desire to.

This, by the way, is the Ruth Robbins painting Le Guin mentions liking.

As I thought about all of this, I was reminded of the fuss over Rue, when the Hunger Games movie came out. Rue was played by Amandla Sternberg, an African American actor. Some fans were shocked—and even angry—to see Rue portrayed as black. But as numerous commentators pointed out at the time, the book specifically identified Rue as having “dark brown skin and eyes.” This was no embellishment on the part of the movie.

Critics of the line of argument I am about to take may point to A Wrinkle in Time. Certainly, that is an example where a white book character—Meg—is played by an African American actress. I am not saying that movie portrayals must always be identical to book portrayals. There is such thing as creative license.

But there is something completely different when an author goes out of her way to write characters of color into her book only to have cover artist and movie adaptors completely ignore her intent and whitewash her stories.

Whitewashing didn’t start in this century, of course. It goes way back. Here is a medieval painting of Joseph and Potiphar’s wife, by Guido Reni in 1630. Do either of the characters look even vaguely middle eastern or Egyptian?

Here’s an interesting game—find a medieval painting of Joseph and Pharaoh’s wife in which they don’t both look European. Type “Joseph” and “Potiphar’s wife” into google and hit images. This appears to have been very popular subject matter for medieval artists—there are large number of portrayals, in various shades of dress. All are white.

Anyone who wants complain about the alleged “political correctness” involved in changing characters like Meg in A Wrinkle in Time from white to mixed-race need to grapple with our society’s history of whitewashing—of taking characters of color and turning them white in artwork and film. Doing research is a good idea too—there was absolutely no excuse for complaints about Rue’s completely accurate portrayal in the Hunger Games movie.

Also? Maybe shelve your assumptions and stop assuming that every character whose race isn’t described must be white. The default should not be white.

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!