Last night, NPR was on in the kitchen while I washed up after supper. I proceeded to reorganize my Tupperware and mop the floor, because I didn’t want to leave the room—I was riveted. On Little War on the Prairie, producers of This American Life told a story I had heard snippets of before, but with a level of detail that made me feel like I was there. It was the story of the expulsion of the Dakota Indians from Minnesota.

The story went like this: As the fur trade declined through overhunting, the Dakota found themselves badly in debt to the traders they worked with—and the traders also found themselves in debt. So the traders orchestrated a treaty that coerced the Dakota to give up all but a narrow strip of land along the Minnesota River (the Dakota retained about two million acres and gave up thirty-five) in exchange for $3 million.

But the Dakota were deceived.

The translated copy the Dakota were given to discuss omitted details included in the treaty they signed in English. The payment was to be given in annual allotments of food and farm supplies, not in a lump sum up front. The Dakota were given around $300,000 in cash, but only so that they could “settle their affairs”—the very traders involved in creating the treaty walked off with nearly all of that money.

A decade later, the annual allotments stopped coming. The Dakota began to starve. The federal agent responsible for distributing the allotment told them to eat grass. Some young men grew angry, and killed several white men. They knew there would be retaliation, so they—against the wishes of many in Dakota leadership—decided to wage war on Minnesota’s white settlers—a war for their existence. Most Dakota refused to participate.

The young Dakota men raided white settlements. Over the course of about a month, they killed 400-600 white settlers. Henry Sibley, one of the traders who helped orchestrate the original treaty, was tasked with leading the defense. He offered a flag of truce and promised that only those Dakota who had personally attacked settlers would be punished. He lied.

From the program’s transcript:

John Biewen: The Dakota trusted Sibley’s promise that only those who had murdered settlers would be punished. But the 1,700 Dakota civilians were marched 150 miles down the Minnesota River, a mini Trail of Tears. In towns along the way, white people attacked them with rocks, clubs, and knives.

A half-Dakota man named Samuel Brown was long for the march, working for the government. He wrote in his diary that in the town of Henderson, a white woman grabbed a baby from a Dakota woman’s arms and threw it at the ground, killing the baby.

The Dakota walked for a week, says historian Mary Wingerd, until they reached their destination near St. Paul.

Mary Wingerd: What was essentially a concentration camp at Fort Snelling, where they were kept until the spring of 1863. And then they were transported to a reservation, Crow Creek, South Dakota. It was in Dakota Territory, which was the next best thing to hell. And the death toll was just shocking.

John Biewen: Hundreds of Dakota, mostly children and old people, died of disease over the winter in Fort Snelling. About 100 more died on boats that took them down the Mississippi and up the Missouri to Dakota Territory.

Still more hundreds died at the South Dakota reservation. As Wingerd puts it, this was the thanks most of the Dakota got for opposing the war.

A year or two ago I spent Thanksgiving reading Jill Lepore’s book about King Philip’s War. As children, we all learned about Massasoit, the Wampanoag chief who shared the First Thanksgiving with the Pilgrims. What we didn’t learn is that his son’s head ended up on a pike outside Plymouth, or that his grandson would be sold into slavery in the West Indies along with hundreds of his people. For some reason, this isn’t taught in school.

I’ve visited the Battle of Little Bighorn. I learned about the treaties that were made, and broken, in the Black Hills. These were stories I’d heard before, stories that are fairly well known today. This may be why I was actually more effected when, after stopping at Julesburg, Colorado, I grew curious about the town’s square shape and looked up its history— only to find a story of war, deception, and massacre that I had never heard before.

In 1865, Julesburg was raided by a group of young Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Lakota men in retaliation for the Sand Creek Massacre. During a period of conflict, John Evans, governor of the territory of Colorado, had invited Indians who desired peace to camp nearby for protection. Colonel John Chivington surrounded the camp of unarmed, peaceful Indians—the majority of them women and children—and killed them all.

The attack and subsequent slaughter was so horrific that several of Chivington’s men refused to shoot. They wrote horrified letters to family members, letters that survive to this day.

We’re working backward here, so what was the conflict that lead to Evans asking peaceful Indians to camp nearby? It went like this:

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 guaranteed ownership of the area north of the Arkansas River to the Nebraska border to the Cheyenne and Arapahoe. However, by the end of the decade, waves of Euro-American miners flooded across the region in search of gold in Colorado’s Rocky Mountains, placing extreme pressure on the resources of the arid plains.

By 1861, tensions between new settlers and Native Americans were rising. On February 8 of that year, a Cheyenne delegation, headed by Chief Black Kettle, along with some Arapahoe leaders, accepted a new settlement with the Federal government. The Native Americansceded most of their land but secured a 600-square mile reservation and annuity payments. The delegation reasoned that continued hostilities would jeopardize their bargaining power. In the decentralized political world of the tribes, Black Kettle and his fellow delegates represented only part of the Cheyenne and Arapahoe tribes. Many did not accept this new agreement, called the Treaty of Fort Wise.

The new reservation and Federal payments proved unable to sustain the tribes. During the Civil War, tensions again rose and sporadic violence broke out between Anglos and Native Americans.

All of this came out of looking up the history of a random Colorado town.

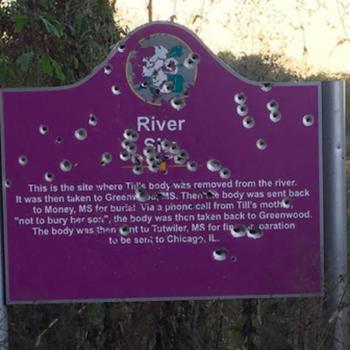

But you know what? This kind of thing isn’t isolated. It’s not really about random towns. Every place in this whole damn country has its stories. If you live in the U.S., the place you are standing on once belonged to one Native American group or another. This was their home. It was taken from them. There are treaties and wars and massacres etched into the story of the land you are standing on. The land has a history.

The land is Native land.

Here is my challenge to you today: If you don’t know them already, learn those stories. Who lived here, before? You can start on this website—but don’t stop there. Research the treaties, how they were made and whether they were kept. Look up the wars, and find out why they were fought, and how, and by whom.

What then? Tell the people around you. Share the information you’ve learned. Teach your children. If there are Native American groups still in your area, consider attending one of their events or lectures, if they are open to the public. Support a Native American nonprofit. Vote for candidates that support Native American rights.

Listen to Native American activists. Learn about their causes.

We cannot undo history, but we can play a role, however small, in breaking the cycle.

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!