Stepping Heavenward, chapter I, part 3

On February 17th, Katy is still at home sick.

It is more than a month since I took that cold, and here I still am, shut up in the house. To be sure the doctor lets me go down stairs, but then he won’t listen to a word about school. Oh, dear! All the girls will get ahead of me.

Stepping Heavenward is loosely based on the author’s own life, and Elizabeth Prentiss had chronic health problems. As the book goes on, we’ll see Katy deal with illness that keeps her in her room for months at a time on multiple occasions.

When I read books written in the past, as this one is, I find it very tempting to try to match characters’ illnesses with modern diagnoses. Perhaps Katy is a celiac, I wondered—celiac was only identified after WWII (which is a fascinating story, by the way). However, Katy is sometimes described as having problems with her lungs, and the term “consumptive” is used.

One problem with trying to diagnose characters’ illnesses in books like this, too, is the sheer number of factors to account for. For instance, in this period people used wood or coal for heat, and soot and ash and dust were all over the place—especially in cities, but not only in cities. Additionally, ordinary illnesses we consider simple to treat today could sometimes leave someone’s immune system weakened, leading to chronic health problems without need for another explanation.

Katy, by the way, has a brother.

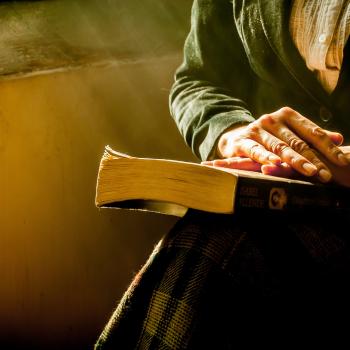

This is Sunday, and everybody has gone to church. I thought I ought to make a good use of the time while they were gone, so I took the Memoir of Henry Martyn, and read a little in that. I am afraid I am not much like him. Then I knelt down and tried to pray. But my mind was full of all sorts of things, so I thought I would wait till I was in a better frame.

Henry Martyn was an anglican priest who went on a mission to India and Persia, translated the New Testament into three languages, and in 1812 died of the plague in what is now Turkey, at age 31. You can read his full memoir online here.

Prentiss’ constant name-dropping of books stands in a bit of a contrast to Janette Oke’s Love Comes Softly, where Clark was frequently described as reading—especially during the winter—but we were never told just what he was reading. The family’s seemingly easy access to books may also stand as another marker of class statues—remember that in Little Women, Jo is always exclaiming over Aunt March’s library.

To return to Katy, though, I think the import here is that Katy is trying to read devotional and inspirational literature like her mother does, but she doesn’t enjoy it the way her mother does. She concludes that she’s just not in the right frame of mind. As if to hammer that in, she continues her diary entry as follows:

At noon I disputed with James about the name of an apple. He was very provoking, and said he was thankful he had not got such a temper as I had. I cried, and mother reproved him for teasing me, saying my illness had left me nervous and irritable. James replied that it had left me where it found me, then.

I like books where sibling relationships feel real, and based on what little we’ve been given so far, this one does. My two children would definitely dispute about the name of an apple.

In conservative Christian homeschool circles, the glorification of large families is often linked to a claim that this is how families once were. There are also arguments made about letting God decide how many children you have, and children always, always, always being a blessing, of course—but there’s an element of this community’s idealization of large families that is linked to its idealization of the past.

But James is Katy’s only sibling. There were several other baby boys, but they died in infancy or early childhood, leaving just James and Katy. In the past, though, you wouldn’t have seen families like the Duggars, with 19 children, all of whom lived past in childhood. Nearly every family lost children. In Little Women, Beth dies—and we see the Hummel baby die as well. In the Laura Ingalls Wilder series, the family loses a baby boy.

Anyway, let’s move along!

This part of the book is filled with Katy’s angst over whether she really loves God. I’m going to leave most of it out because it’s very repetitive, but I wanted to include this one bit, from a February 20th entry, by way of example:

It has been quite a mild day for the season, and the doctor said I might drive out. I enjoyed getting the air very much. I feel just well as ever, and long to get back to school. I think God has been very good to me in making me well again, and wish I loved Him better. But, oh, I am not sure I do love Him! I hate to own it to myself, and to write it down here, but I will. I do not love to pray. I am always eager to get it over with and out of the way so as to have leisure to enjoy myself. I mean that this is usually so. This morning I cried a good deal while I was on my knees, and felt sorry for my quick temper and all my bad ways. If I always felt so, perhaps praying would not be such a task. I wish I knew whether anybody exactly as bad as I am ever got to heaven at last.

And then we get this bit:

I have read ever so many memoirs, and they were all about people who were too good to live, and so died; or else went on a mission. I am not at all like any of them.

People who died because they were too good to live was a real trope of this time. I once heard a talk by an academic who looked at antebellum religious journals and children’s literature and found that they were full of stories of children who were good, pure, and almost too kind to be true who then died, urging the adults around them to turn to Jesus with their dying words. The presenter suggested that these stories, augmented and tailored in specific ways, were a way parents and communities sought to come to terms with childhood death at the time.

You see just a little bit of this trope in Beth’s death, though tailored through a slightly different religious lens (as a number of readers have noted, Alcott was a Unitarian, and grew up in a Transcendentalist home).

On March 26th Katy writes that she is finally feeling better.

Somehow I have been behaving quite nicely lately. Everything has gone on exactly to my mind. Mother has not found fault with me once, and father has praised my drawings and seemed proud of me. He says he shall not tell me what my teachers say of me lest it should make me vain. And once or twice when he has met me singing and frisking about the house he has kissed me and called me his dear little Flibbertigibbet, if that’s the way to spell it. When he says that I know he is very fond of me. We are all very happy together when nothing goes wrong.

I mentioned in introducing this series that Katy’s father is dispatched early, just as the girls’ father in Little Women is absent due to the war. Well, Katy’s father hasn’t been dispatched yet.

I have a good deal of time to read, and I devour all the poetry I can get hold of. I would rather read “Pollok’s Course of Time” than read nothing at all.

This is, apparently, a single poem that takes up ten books. You can read it here. I found an article about the poem, but it’s behind a paywall. Suffice it to say that this is a religious poem, evangelical in nature, published by a Scottish point in 1827. Based on her “nothing at all” comment, it sounds as though Katy has been limited to religious literature during her convalescence, and that this is the most interesting she can find.

On April 2nd, Katy writes as follows:

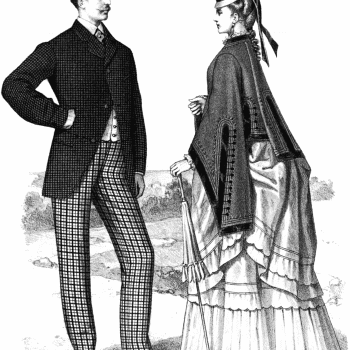

There are three of mother’s friends living near us, each having lots of little children. It is perfectly ridiculous how much those creatures are sick. They send for mother if so much as a pimple comes out on one of their faces. When I have children I don’t mean to have such goings on. I shall be careful about what they eat, and keep them from getting cold, and they will keep well of their own accord. Mrs. Jones has just sent for mother to see her Tommy. It was so provoking. I had coaxed her into letting me have a black silk apron; they are all the fashion now, embroidered in floss silk. I had drawn a lovely vine for mine entirely out of my own head, and mother was going to arrange the pattern for me when that message came, and she had to go. I don’t believe anything ails the child! A great chubby thing!

A friend of mine noted that one difference between Little Women and Stepping Heavenward is that Jo and her sisters, for all their faults, are likable, and that Katy is not. This is one area where you can see that in stark relief. The March girls readily gave up their Christmas breakfast so that the Hummel children could have something to eat. You get the feeling Katy would have complained till kingdom come, insisting that the Hummels probably had food squirreled away somewhere—that the children didn’t look hungry—or some such nonsense.

On April 3rd, Katy writes the following:

Poor Mrs. Jones! Her dear little Tommy is dead! I stayed at home from school to-day and had all the other children here to get them out of their mother’s way. How dreadfully she must feel! Mother cried when she told me how the dear little fellow suffered in his last moments. It reminded her of my little brothers who died in the same way, just before I was born. Dear mother! I wonder I ever forget what troubles she has had, and am not always sweet and loving. She has gone now, where she always goes when she feels sad, straight to God. Of course she did not say so, but I know mother.

Are we to imagine that Katy learned anything from this? If so, it’s not stated explicitly.

But! I did title this piece brother trouble! So far the only thing we’ve seen of James is Katy’s argument with him over the name of an apple. Never fear! Here we go!

On April 25th, we have the following:

I have not been down in season once this week. I have persuaded mother to let me read some of Scott’s novels, and have sat up late and been sleepy in the morning. I wish I could get along with mother as nicely as James does. He is late far oftener than I am, but he never gets into such scrapes about it as I do.

Some parents do have double standards, and treat their children differently. I don’t think that’s what we’re supposed to assume here, necessarily, though, because—well, I’ll let you read:

This is what happens. He comes down when it suits him.

Mother begins.-“James, I am very much displeased with you.”

James.-“I should think you would be, mother.”

Mother, mollified.-“I don’t think you deserve any breakfast.”

James, hypocritically.-“No, I don’t think I do, mother.”

Then mother hurries off and gets something extra for his breakfast.

So, James is properly self-effacing and is served breakfast anyway. Are we to understand that James is sucking up to their mother in these moments? Or is he honestly serious that he doesn’t deserve any breakfast? And why does their mother get him breakfast anyway? Is it because he’s properly sorry for being down late? But if he says the exact same thing every time, is he sorry, really?

Katy offers this as contrast:

Now let us see how things go on when I am late.

Mother.-“Katherine” (she always calls me Katherine when she is displeased, and spells it with a K), “Katherine, you are late again; how can you annoy your father so?”

Katherine.-“Of course I don’t do it to annoy father or anybody else. But if I oversleep myself, it is not my fault.”

Mother.-“I would go to bed at eight o’clock rather than be late as often as you. How should you like it if I were not down to prayers ?”

Katherine, muttering.-“Of course that is very different. I don’t see why I should be blamed for oversleeping any more than James. I get all the scoldings.”

Mother sighs and goes off.

I prowl round and get what scraps of breakfast I can.

Katy responds by being immediately combative—although I should note that her mother’s initial comment to her is more combative than her initial comment to James, in that initial example.

I’d love to hear more from my readers on the purpose of this section. Is the reader to come away thinking Katy is ridiculous to not see that the difference in response she gets is due to her attitude? I sincerely doubt we’re to think that she is in fact receiving harsher treatment than her brother. Instead, I think we’re to see her as petulant and argumentative.

And how are we to view Katy’s brother, James, in this example? As someone who is genuine and is responding properly, or as someone who is being manipulative, or a bit of a goody-two-shoes?

If this were Little Women, Katy would be petulant and rude, and then feel terrible about treating her beloved Marmee that way, and then go throw herself on Marmee with profuse apologies for being so very mean, and Marmee would sweep the hair back from the girl’s forehead and say something profound and actually helpful. But no. That is not at all what happens.

Petulant Katy will go on being petulant.

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!