Stepping Heavenward, chapter I, part 4

The year is still 1831, and Katy is still sixteen.

May 12.- The weather is getting perfectly delicious. I am sitting with my window open, and my bird is singing with all his heart. I wish I was as gay as he is.

This really frames this section well.

I have been thinking lately that it was about time to begin on some of those pieces of self-denial I resolved on upon my birthday. I could not think of anything great enough for a long time. At last an idea popped into my head. Half the girls at school envy me because Amelia is so fond of me, and Jane Underhill, in particular, is just crazy to get intimate with her. But I have kept Amelia all to myself.

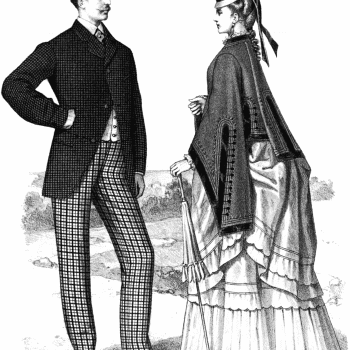

I’ve been trying to think of a parallel in another piece of literature from this general time period. We don’t see friendships of this sort in Little Women because the sisters seem to spend most of their time with each other—instead, we see close friendships between the sisters. I can’t recall anything quite of this sort of thing in Little House on the Prairie, either, perhaps because they were always moving. But I don’t remember this in Elsie Dinsmore or The Little Colonel, either, two books set in the South at around this time or slightly later. There is Anne of Green Gables, though, with Anne’s “bosom” friendship with Diana.

Of course, the concept of having a “best” friend is still present today, and teenage girls today do have “friend drama”—or whatever we want to call it—which is what this turns into. Still, there’s something about the language here that’s different.

To-day I said to her, Amelia, Jane Underhill admires you above all things. I have a good mind to let you be as intimate with her as you are with me. It will be a great piece of self-denial, but I think it is my duty. She is a stranger, and nobody seems to like her much.”

“You dear thing, you!” cried Amelia, kissing me. “I liked Jane Underhill the moment I saw her. She has such a sweet face and such pleasant manners. But you are so jealous that I never dared to show how I liked her. Don’t be vexed, dearie; if you are jealous it is your only fault!”

She then rushed off, and I saw her kiss that girl exactly as she kisses me!

Note the terminology in this section: Katy tells her friend Amelia that their classmate Jane Underhill “admires you above all things,” and gives Amelia permission to “be as intimate with her as you are with me.” After “kissing” Katy, Amelia runs off and to “kiss” Jane the same way, making Katy jealous. Katy would probably only use language like this today if she were in fact “as gay as” the bird singing outside of her window. Apart from this section, though we’re never given any suggestion that Katy same-sex attractions. So what’s going on?

I find myself extremely curious about the evolution of language over time, and about female friendships and intimacy in the 1800s. I know there were women who had romantic or sexual relationships with other women—even living with them—largely without being detected. The presence of this sort of language has to have helped. Indeed, one book on lesbianism in the nineteenth century is titled Intimate Friends: Women Who Loved Women, 1778-1928.

Let’s set the language aside for the moment and look at what actually happened here. Amelia describes this incident as an attempt to practice self-denial. This is an odd sort of self denial. If Jane Underhill is lonely and doesn’t have any friends—as it sounds like is the case—why doesn’t Katy take Jane under her wing, or bring Jane into her and Ameilia’s friend group? And why does Amelia need Katy’s permission to go talk to Jane? Is this how it is in public high school today, and I just missed it because I was homeschooled? Or is this something more specific to the time period, along the lines of Anne’s “bosom” friendship with Diana?

Either way, Katy is upset. She was trying to do a good thing, but it sounds like she didn’t really want Amelia to take her up on it—and now she’s hurt and jealous. Katy genuinely doesn’t sound like that nice of a person, but remember—we’re meant to think that her problem is that she doesn’t like to pray.

One of the biggest differences between Stepping Heavenward and Little Women is that Katy’s faults are framed as spiritual ones while the March girls’ faults, while still framed as things they need to do battle against, are framed more mundanely. We’ll see this next week, when we’ll have time to do a direct comparison.

Of all of the girls in Little Women, Amy is the one who reads as most similar to Katy, which its funny, because Amy is twelve and Katy is sixteen. Amy wants to be popular at school, and yes, there is drama. But what is cute at 12—her older sisters find the scrapes she get herself in funny—is not as attractive at 16.

This was in recess. I went to my desk and made believe I was studying. Pretty soon Amelia came back.

“She is a sweet girl,” she said, “and only to think! She writes poetry! Just hear this! It is a little poem addressed to me. Isn’t it nice of her?”

I pretended not to hear her. I was as full of all sorts of horrid feelings as I could hold. It enraged me to think that Amelia, after all her professions of love to me, should snatch at the first chance of getting a new friend. Then I was mortified because I was enraged, and I could have torn myself to pieces for being such a fool as to let Amelia see how silly I was.

The terminology here is utterly fascinating.

“I don’t know what to make of you, Katy,” she said, putting her arms round me. “Have I done anything to vex you? Come, let us make up and be friends, whatever it is. I will read you these sweet verses; I am sure you will like them.”

She read them in her clear, pleasant voice.

“How can you have the vanity to read such stuff?” I cried.

Amelia colored a little.

“You have said and written much more flattering things to me,” she replied. “Perhaps it has turned my head, and made me too ready to believe what other people say.” She folded the paper, and put it into her pocket.

All of this has left Katy deep in a spat with her best friend and extremely out of sorts in general.

We walked home together, after school, as usual, but neither of us spoke a word. And now here I sit, unhappy enough. All my resolutions fail. But I did not think Amelia would take me at my word, and rush after that stuck-up, smirking piece.

Compared to the other works I have reviewed, this book feels more genuine and real. Katy has gone from thinking very little of Jane Underhill one way or another to describing her as a “stuck-up, smirking piece,” for seemingly no reason. What did Jane do that suddenly revealed her as “stuck-up” or “smirking”? Nothing. But she didn’t have to. This sudden mean-spirited description of Jane, born out of emotion and not out of reality, is very, very human—and all too familiar.

Even knowing how human this reaction is, though, I’m having a hard time feeling very sorry for Katy, which is probably the point. Katy is vain and selfish. She is not particularly likable, because she still needs the sanctification that comes from God, through his son Jesus. As long as she focuses on herself and her own pleasure, and not on God and his love for her, she will remain unlikeable.

In Little Women, both Meg and Amy experience a love for fine things, and are jealous of those who have what they do not. Amy desires to be admired and liked, and sometimes makes missteps on this path that send her sisters into gales of laughter. But neither Meg nor Amy come across as unlikable in the way Katy does. And in both cases, their foibles are treated as things they will be able to overcome with maturity and wisdom as they grow, and not as spiritual shortcomings.

Katy, though, is thoroughly out of patience.

May 20.- I seem to have got back into all my bad ways again. Mother is quite out of patience with me. I have not prayed for a long time. It does not do any good.

Oh—and Amelia still isn’t talking to her. There is an element of this that is simply what we call “teenage drama” today. Katy is on the outs with her best friend. Of course she’s upset. This is something we can understand. But it strikes me that teenage girls of the time were given a vocabulary—and permission to engage in a depth of friendship—that is different from what teenage girls are given today.

I have taken only one graduate class on sexuality and gender, and that single class left me vividly aware only of how much I don’t know. If anyone has articles or books that would shed light on this chapter and this time period, I’m all ears!

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!