Stepping Heavenward, Chapter I, Part 1

January 15, 1831

Little Women, by Louisa May Alcott, was published in 1868. Stepping Heavenward, by Elizabeth Prentiss, was published in 1869. As I reread Stepping Heavenward this week, I also picked up Little Women, to have a point of comparison. Doing this was absolutely fascinating.

I’d forgotten that, at the beginning of Little Women, Marmee gives each of her girls their own attractive leather-bound Bible and entreats them to read it. I’d forgotten, too, that Marmee refers to Jesus as the best friend a girl could have, and encourages her girls to take their faults to Him. Here, though, is also where the two books differ—Alcott does not include the words “Bible” or “Jesus” in her book, instead referencing each in roundabout ways. Not so Prentiss.

In Alcott, the emphasis is on raising good Christian women. In Prentiss, the emphasis is on raising good Christian women. The girls in each book are encouraged to learn to control their tempers, entreated not to value worldly, material things, and urged to care for the poor. But in Prentiss, characters must learn to overcome their faults because these faults are sins that grieve Christ; while in Alcott, learning to be good is treated as a virtue in and of itself.

I picked up Little Women again in part because of how much Katy, the main character in Prentiss’ book, reminded me of both Jo and Meg. She reminded me of Jo, because she has a temper, and a wildness and depth of feeling and passion. She reminded me of Meg, in her longing to be fashionable and well-dressed, a lady and well-liked in her social circles.

But Katy also differs from both Jo and Meg in one very big respect—she spends her entire teenage years wracked with doubt and angst over whether she truly loves Jesus. You never hear angst of that sort in Little Women. To be sure, the March girls sometimes mourn their faults, declaring themselves horrible people as they do so, but then there’s Marmee there to encourage them to master their faults, and to praise all of their good characteristics. No one ever sends them off to the minister, or connects their failings to spiritual struggles.

There’s an underlying surety in oneself in Little Women that is absent from much of Stepping Heavenward. The amount of time this book covers is another difference between the two—Stepping Heavenward may begin in 1831 when Katy is 16, the same age Meg is at the beginning of Little Women, but it ends in 1858, when Katy is 43. The first third of the book covers Katy’s girlhood, and the next third her early married years. By the last third of the book, Katy has finally obtained a confidence in her faith that gives her peace in who she is.

While each book is ostensibly focused on the girls (Katy in the one, Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy in the other), each book is grounded in the stable, quieting influence of a mother figure. Like Marmee in Little Women, Katy’s mother is always there to pick Katy up after she falls, and to dispense advice and words of wisdom. Katy, like the girls in Little Women, adores her mother. The role of the mother in each book is so strong, and so central, that I suspect the two books were both influenced by similar trends in genre and tropes of their time.

There is also another similarity between the two books as well—each centers on a family in the growing middle class, with an educated father with a profession and a mother who manages her household and servants and visits the poor. (Each author dispenses with the father figure: in Little Women, the girls’ father is a chaplain in the army; in Stepping Heavenward, Katy’s father dies in the first chapter.) Further, while each family can afford servants, neither has expansive resources and each feels the pinch of poverty relative to other families of their status.

Again, I wonder whether these similarities stem from trends in genre at the time. While Little Women was published first, Stepping Heavenward came out too soon after it (it was published the following year) and is different enough from it that it is unlikely that it was a copy-cat work.

The most significant difference between the two works is in form. While Little Women is written in the third person, Stepping Heavenward takes the form of a journal. While Katy recounts stories and exploits in her journal, she tells them from her perspective and surrounds them with long running paragraphs of spiritual angst. Sometimes, her entries skip months or even years, allowing the reader to fly forward in her life as she fills in some of what her entries have missed.

But enough with these comparisons! It’s time I gave you all a taste of Stepping Heavenward.

I’m going to give you a rather large excerpt to start with, the first few pages of the book. After this I’ll do more by way of summary, but reading this bit through in its entirety should help you get a feel for this book—and for Katy—from the outset.

CHAPTER I. JANUARY 15, 1831

How dreadfully old I am getting! Sixteen! Well, I don’t see as I can help it. There it is in the big Bible in father’s own hand: “Katherine, born Jan. 15, 1815.”

I meant to get up early this morning, but it looked dismally cold out of doors, and felt delightfully warm in bed. So I covered myself up, and made ever so many good resolutions.

I determined, in the first place, to begin this Journal. To be sure, I have begun half a dozen, and got tired of them after a while. Not tired of writing them, but disgusted with what I had to say of myself. But this time I mean to go on, in spite of everything. It will do me good to read it over, and see what a creature I am.

Then I resolved to do more to please mother than I have done.

And I determined to make one more effort to conquer my hasty temper. I thought, too, I would be self-denying this winter, like the people one reads about in books. I fancied how surprised and pleased everybody would be to see me so much improved!

Time passed quickly amid these agreeable thoughts, and I was quite startled to hear the bell ring for prayers. I jumped up in a great flurry and dressed as quickly as I could. Everything conspired together to plague me. I could not find a clean collar, or a handkerchief. It is always just so. Susan [one of their servants] is forever poking my things into out-of-the-way places! When at last I went down, they were all at breakfast.

“I hoped you would celebrate your birthday, dear, by coming down in good season,” said mother.

I do hate to be found fault with, so I fired up in an instant.

“If people hide my things so that I can’t find them, of course I have to be late,” I said. And I rather think I said it in a very cross way, for mother sighed a little. I wish mother wouldn’t sigh. I would rather be called names out and out.

So, this is Katy. Passionate and impulsive and forever making resolutions to do good only to rise to meet the next provocation life hands her—and to her view, and hands her a lot.

Having finished breakfast, Katy has to run to school. Her mother tells her that it has snowed and that she should wear her overshoes, but Katy says she doesn’t need them and that she’ll be late if she has to go looking for them (it seems she has lost them).

“Do let me go, mother,” I cried. “I do wish I could ever have my own way.”

“You shall have it now, my child,” mother said, and went away.

Now what was the user of her calling me “my child” in such a tone, I should like to know.

Katy arrives at school and is pleased to find that her best friend, Amelia, has brought her a knit purse and a hair net as gifts.

Amelia wrote me a dear little note, with her presents. I do really believe she loves me dearly. It is so nice to have people love you!

Over time, Katy will come to see this as one of her biggest faults—she wants to be liked. She cares what other people think about her. She wants always to be the center of attention.

But first, her mother.

When I got home mother called me into her room. She looked as if she had been crying. She said I gave her a great deal of pain by my self-will and ill temper and conceit.

“Conceit!” I screamed out. “Oh, mother, if you only knew how horrid I think I am!”

Mother smiled a little. Then she went on with her list till she made me out the worst creature in the world. I burst out crying, and was running off to my room, but she made me come back and hear the rest.

Katy’s mother really is quite different from Marmee in a number of respects. This is one of them. I can’t imagine Marmee making birthdays occasions for laying out her children’s faults. I also can’t imagine her crying over one of her children’s faults on their birthday.

The smile Katy’s mother gives when Katy declares that she views herself as a horrid person rubs me incredibly wrong. It is possible that this smile is an attempt to conceal her mirth at Katy’s passion in declaring herself a horrible person. Perhaps. But more likely, I think, this smile suggests that she is pleased that Katy is dissatisfied with Katy’s current state, as she is.

She said my character would be essentially formed by the time I reached my twentieth year, and left it to me to say if I wished to be as a woman what I was now as a girl. I felt sulky, and would not answer. I was shocked to think I had got only four years in which to improve, but after all a good deal could be done in that time. Of course I don’t want to be always exactly what I am now.

Ugh. Poor Katy. Katy needs therapy. Katy’s mother needs therapy. Everyone needs therapy.

When I perceive that one of my own children has a fault, I definitely do talk to them about it. But not like this. Firstly, I don’t view self-will as a fault. Katy’s headstrong nature itself isn’t a bad thing. Second, when it comes to ill temper or flying into passions—as with Katy—I typically view this as a lack of proper tools. Learning to manage one’s emotions in a healthy way is an important life skill that has to be learned. This is where therapy can—and does—come in.

When one of my children flies into a passion, I typically ride it out, taking the path of least resistance—in other words, giving them the space they need to calm down. Then, later, we talk about it. They don’t like severe emotional swings any more than I do. So we talk about it. I ask what could have been done differently, on both my and their part. We come up with a plan for how to handle things better next time, we talk about tools, we practice.

Is Katy given tools? No. No, she isn’t.

One of my children has seen a therapist who has worked with them on emotional regulation—on things like techniques for calming down, tools for self advocacy, etc. This process has been incredibly helpful—it turns out that having tools is important! Furthermore, because we don’t treat emotional dysregulation as sin or a spiritual fault—as Katy’s mother does—there is no guilt or shame involved in this process.

Not so for poor Katy.

Mother went on to say that I had in me the elements of a fine character if I would only conquer some of my faults. “You are frank and truthful,” she said, “and in some things conscientious. I hope you are really a child of God, and are trying to please Him. And it is my daily prayer that you may become a lovely, loving, useful woman.”

It’s interesting to contrast these words with what Marmee would have said. Marmee did talk with her girls about conquering their faults, and, if asked, would likely have said that she hoped each of her girls would grow into lovely, loving, useful women. But Marmee didn’t talk about God quite so directly, and she also wanted her girls to be happy.

I made no answer. I wanted to say something, but my tongue wouldn’t move. I was angry with mother, and angry with myself. At last everything came out all in a rush, mixed up with such floods of tears that I thought mother’s heart would melt, and that she would take back what she had said.

“Amelia’s mother never talks so to her!” I said. “She praises her, and tells her what a comfort she is to her. But just as I am trying as hard as I can to be good, and making resolutions, and all that, you scold me and discourage me!”

Does anyone want to guess what happens to Amelia? Let’s just say that Amelia is to this book what Julia was to A Voice in the Wind and what Laura was to Love Comes Softly. Like Julia and Laura, Amelia will not be allowed to live.

“I am very sorry for you, dear,” mother replied. “But you must bear with me. Other people will see your faults, but only your mother will have the courage to speak of them. Now go to your own room, and wipe away the traces of your tears that the rest of the family may not know that you have been crying on your birthday.”

Okay, cool. Reading Katy a laundry list of her faults on her birthday is a-okay, but god forbid she look like she’s been crying on her birthday! Really, what did she think would happen?

Katy runs off, angry.

I ran across the hall to my room, slammed the door, and locked myself in. I was going to throw myself on the bed and cry till I was sick. Then I should look pale and tired, and they would all pity me. I do like so to be pitied! But on the table, by the window, I saw a beautiful new desk in place of the old clumsy thing I had been spattering and spoiling so many years.

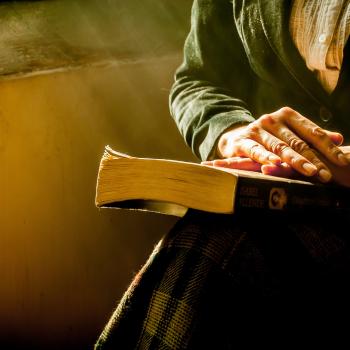

Katy looks in the desk and finds paper, and seals, and wax, and pens. She is thrilled. And of course, there’s also a note with it from her mother, and a new, tastefully bound copy of the Bible. The note urged Katy to “read and reflect upon a few verses,” explaining that:

“A few verses,” she said, “carefully read and pondered, instead of a chapter or two read for mere form’s sake.”

I was assigned to read whole chapters when I was a child and teen, in an attempt to read the Bible through every three years. There were some benefits to this. In reading chapters, you got the context of individual verses. Ideally, you’d read a bit about each book of the Bible and its author before starting it, so you’d understand better what it was trying to do.

Of course, I was something of a Bible snob, and I must admit to feeling that those who read and pondered on only a few verses were taking a short cut in the interest in saving time and avoiding the greater work involved in reading and studying longer passages.

To be fair to my teenage snobbery, though, reading full chapters rather than pondering individual verses did help avoid this problem:

Then I opened the Bible at random, and lighted on these words: “Watch, therefore, for ye know not what hour your Lord doth come.” There was nothing very cheering in that. I felt a real repugnance to be always on the watch, thinking I might die at any moment.

I’m somewhat curious, now, about the history of different schools of thought about how to read the Bible. Is Katy’s mother’s suggestion that she only read a few verses meant to be an insertion in theological discussions of the time of the most effective methods of devotional Bible reading? I suspect that we are to think she was right in her suggestion, because even though Katy pushes this verse aside, it clearly makes her think about her mortality.

I am sure I am not fit to die. Besides I want to have a good time, with nothing to worry me. I hope I shall live ever so long. Perhaps in the course of forty or fifty years I may get tired of this world and want to leave it. And I hope by that time I shall be a great deal better than I am now, and fit to go to heaven.

I wrote a note to mother on my new desk, and thanked her for it I told her she was the best mother in the world, and that I was the worst daughter.

Is this meant to be seen as hyperbole? Katy spends the entire first third of this book talking about what an awful person she is, even as she then runs off to amusements. If my child was constantly going on and on about what a horrid person they are, I’d be worried. Here though, it’s a sign that she has spiritual unrest and will keep seeking until she finds God.

Having written this letter, Katy goes downstairs and has a lovely birthday dinner. She finds that her mother even invited Amelia. Katy’s birthday ends as she hops in bed to say her prayers under the covers, because she’s too cold and tired to kneel by her bed for her prayers as is her usual practice. We’re meant to see that as a bad decision, of course.

Anyway. More on Katy’s life next week!

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!