Stepping Heavenward, chapter I, part 5

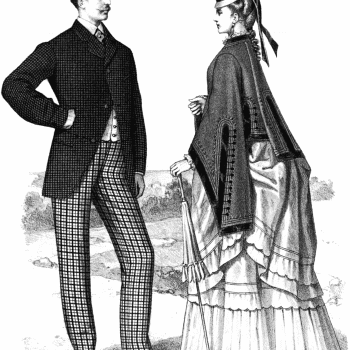

This week is an interesting one, because it’s going to allow us to make a direct comparison between Stepping Heavenward and Little Women. Weirdly direct. Essentially the exact same conversation takes place between Marmee and Jo, and between Katy and her mother—except that the two are actually very different.

Let’s start with Katy and her mother:

May 21.-It seems this Underhill thing is here for health, though she looks as well as any of us. She is an orphan, and has been adopted by a rich old uncle, who makes a perfect fool of her. Such dresses and such finery as she wears! Last night she had Amelia there to tea, without inviting me, though she knows I am her best friend. She gave her a bracelet made of her own hair. I wonder Amelia’s mother lets her accept presents from strangers. My mother would not let me. On the whole, there is nobody like one’s own mother. Amelia has been cold and distant to me of late, but no matter what I do or say to my darling, precious mother, she is always kind and loving. She noticed how I moped about to-day, and begged me to tell her what was the matter. I was ashamed to do that. I told her that it was a little quarrel I had had with Amelia.

“Dear child,” she said, “how I pity you that you have inherited my quick, irritable temper.”

“Yours, mother!” I cried out; “what can you mean?”

Mother smiled a little at my surprise.

“It is even so,” she said.

“Then how did you cure yourself of it? Tell me quick, mother, and let me cure myself of mine.”

When I read the above section, I immediately pulled out my copy of Little Women, because I remembered something. At one point early in the book, Amy gets angry at Jo for not including her in an outing, and puts Jo’s manuscript in the fire. Jo refuses to forgive her, and one day. Amy follows Laurie and Jo—who is still ignoring her—to the river to skate, and goes through the ice. And yes—there it was.

After Jo and Laurie pull Amy out of the water and take her home, and after Marmee makes sure Amy is warm and assures Jo that Amy will be okay, Marmee turns to Jo, who is distraught over her actions.

The following exchange takes place:

“It’s my dreadful temper! I try to cure it, I think I have, and then it breaks out worse than ever. Oh, Mother, what shall I do? What shall I do?” cried poor Jo, in despair.

“Watch and pray, dear, never get tired of trying, and never think it is impossible to conquer your fault,” said Mrs. March, drawing the blowzy head to her shoulder and kissing the wet cheek so tenderly that Jo cried even harder.

“You don’t know, you can’t guess how bad it is! It seems as if I could do anything when I’m in a passion. I get so savage, I could hurt anyone and enjoy it. I’m afraid I shall do something dreadful some day, and spoil my life, and make everybody hate me. Oh, Mother, help me, do help me!”

“I will, my child, I will. Don’t cry so bitterly, but remember this day, and resolve with all your soul that you will never know another like it. Jo, dear, we all have our temptations, some far greater than yours, and it often takes us all our lives to conquer them. You think your temper is the worst in the world, but mine used to be just like it.”

“Yours, Mother? Why, you are never angry!” And for the moment Jo forgot remorse in surprise.

There is an uncanny similarity here.

“Dear child, how I pity you that you have inherited my quick, irritable temper.”

“You think your temper is the worst in the world, but mine used to be just like it.”

“Yours, mother! What can you mean?”

“Yours, Mother? Why, you are never angry!”

Almost spooky, isn’t it?

Having looked at the similarity of the setup here, let’s continue to each mother’s response. As before, we’ll start with Katy and her mother.

“My dear Katy,” she said, “I wish I could make you see that God is just as willing, and just as able to sanctify, as He is to redeem us. It would save you so much weary, disappointing work. But God has opened my eyes at last.”

“I wish He would open mine, then,” I said, “for all I see now is that I am just as horrid as I can be, and that the more I pray the worse I grow.”

“That is not true, dear,” she replied; “go on praying-pray without ceasing.”

I sat pulling my handkerchief this way and that, and at last rolled it up into a ball and threw it across the room. I wished I could toss my bad feelings into a corner with it.

“I do wish I could make you love to pray, my darling child,” mother went on. “If you only knew the strength, and the light, and the joy you might have for the simple asking. God attaches no conditions to His gifts. He only says, ‘Ask!'”

“This may be true, but it is hard work to pray. It tires me. And I do wish there was some easy way of growing good. In fact I should like to have God send a sweet temper to me just as He sent bread and meat to Elijah. I don’t believe Elijah had to kneel down and pray for them.

Katy’s mother’s answer is that God is willing to sanctify and redeem her, if she would only ask. There’s no practical advice here at all—the only thing Katy’s mother tells her to do is pray. Given that Katy’s mother knows she doesn’t get much out of prayer—Katy doesn’t exactly hide this—this seems rather unhelpful.

What did Marmee tell Jo, in contrast?

“I’ve been trying to cure it for forty years, and have only succeeded in controlling it. I am angry nearly every day of my life, Jo, but I have learned not to show it, and I still hope to learn not to feel it, though it may take me another forty years to do so.”

I want to pause here to note something real quick. While Marmee says she hopes someday to get over her temper, she tells Jo that she still gets angry. Katy’s mother, in contrast, gave the distinct impression that she has gotten over her temper. “God is just as willing, and just as able to sanctify, as He is to redeem us,” Katy’s mother tells her. Sanctification is the process by which God makes a person increasingly Christ-like.

Much of Prentiss’ book is about the process of sanctification—Katy thinks that if she is saved she will be good, and if she is not good, she worries that that means she is not actually saved. Hence all of her fears over whether she actually loves Jesus, when does so many bad things. Over the course of the book, Prentiss demonstrates to her readers that goodness is only achieved through sanctification over time. Katy’s mother has achieved it.

Unlike Katy’s mother, Marmee does not mention sanctification. But if you look back at the conversation between Jo and Marmee above above, you’ll notice that before she divulges that she too has struggled with a temper, Marmee responds to Jo’s despair over managing her temper by telling her to “watch and pray.” Religion, then, is not absent from Marmee and Jo’s exchange. But there are some pretty significant differences nonetheless.

Back to Jo, and her conversation with Marmee:

The patience and the humility of the face she loved so well was a better lesson to Jo than the wisest lecture, the sharpest reproof. She felt comforted at once by the sympathy and confidence given her. The knowledge that her mother had a fault like hers, and tried to mend it, made her own easier to bear and strengthened her resolution to cure it, though forty years seemed rather a long time to watch and pray to a girl of fifteen.

Can I just say how much I love Alcott’s approach to raising children? Or perhaps it is Abigail May‘s approach we’re seeing here, because in moments like these, Alcott is really writing about her own experiences.

“Mother, are you angry when you fold your lips tight together and go out of the room sometimes, when Aunt March scolds or people worry you?” asked Jo, feeling nearer and dearer to her mother than ever before.

“Yes, I’ve learned to check the hasty words that rise to my lips, and when I feel that they mean to break out against my will, I just go away for a minute, and give myself a little shake for being so weak and wicked,” answered Mrs. March with a sigh and a smile, as she smoothed and fastened up Jo’s disheveled hair.

I could have done without the reference to being “so weak and wicked,” but note that there are practical tips coming out here—tells Jo she walks out of the room when she gets angry, so as not to say things she’ll regret.

“How did you learn to keep still? That is what troubles me, for the sharp words fly out before I know what I’m about, and the more I say the worse I get, till it’s a pleasure to hurt people’s feelings and say dreadful things. Tell me how you do it, Marmee dear.”

“My good mother used to help me…”

“As you do us…” interrupted Jo, with a grateful kiss.

“But I lost her when I was a little older than you are, and for years had to struggle on alone, for I was too proud to confess my weakness to anyone else. I had a hard time, Jo, and shed a good many bitter tears over my failures, for in spite of my efforts I never seemed to get on. Then your father came, and I was so happy that I found it easy to be good. But by-and-by, when I had four little daughters round me and we were poor, then the old trouble began again, for I am not patient by nature, and it tried me very much to see my children wanting anything.”

The Alcotts became poor because Abigail May’s husband, Bronson Alcott, was a man with big ideas but little practical sense when it comes to things like money. He tried to start a commune when Alcott was young, and it failed miserably. He was a Transcendentalist, and was what Debi Pearl would have called a Visionary Man.

“Poor Mother! What helped you then?”

“Your father, Jo. He never loses patience, never doubts or complains, but always hopes, and works and waits so cheerfully that one is ashamed to do otherwise before him. He helped and comforted me, and showed me that I must try to practice all the virtues I would have my little girls possess, for I was their example. It was easier to try for your sakes than for my own. A startled or surprised look from one of you when I spoke sharply rebuked me more than any words could have done, and the love, respect, and confidence of my children was the sweetest reward I could receive for my efforts to be the woman I would have them copy.”

I am fascinated by Marmee’s suggestion that her children helped her become a better person—that as a parent, she was motivated in part by wanting to gain the love, respect, and confidence of her children.

Katy later concludes, when she’s a mother herself, that spending happy and pleasant time with playing her children—and as a consequence having less time for Bible reading—is better than putting Bible reading before all, and snapping at her children when they want to spend time with her. But that’s not quite the same thing.

Anyway, Marmee goes on:

“Oh, Mother, if I’m ever half as good as you, I shall be satisfied,” cried Jo, much touched.

“I hope you will be a great deal better, dear, but you must keep watch over your ‘bosom enemy’, as father calls it, or it may sadden, if not spoil your life. You have had a warning. Remember it, and try with heart and soul to master this quick temper, before it brings you greater sorrow and regret than you have known today.”

“I will try, Mother, I truly will. But you must help me, remind me, and keep me from flying out. I used to see Father sometimes put his finger on his lips, and look at you with a very kind but sober face, and you always folded your lips tight and went away. Was he reminding you then?” asked Jo softly.

“Yes. I asked him to help me so, and he never forgot it, but saved me from many a sharp word by that little gesture and kind look.”

Do you see what I mean about how much more practical this section is in the advice contained, compared with the section in Prentiss’ book, where the only thing Katy is told is to pray that God will sanctify her?

Jo saw that her mother’s eyes filled and her lips trembled as she spoke, and fearing that she had said too much, she whispered anxiously, “Was it wrong to watch you and to speak of it? I didn’t mean to be rude, but it’s so comfortable to say all I think to you, and feel so safe and happy here.”

“My Jo, you may say anything to your mother, for it is my greatest happiness and pride to feel that my girls confide in me and know how much I love them.”

Abigail May wins best mother of the 19th century, in my book.

“I thought I’d grieved you.”

“No, dear, but speaking of Father reminded me how much I miss him, how much I owe him, and how faithfully I should watch and work to keep his little daughters safe and good for him.”

“Yet you told him to go, Mother, and didn’t cry when he went, and never complain now, or seem as if you needed any help,” said Jo, wondering.

The topic is starting to wander, but Marmee is about to bring it back to Jo and Jo’s struggle—and it is here that religion intrudes into the story most fully:

“I gave my best to the country I love, and kept my tears till he was gone. Why should I complain, when we both have merely done our duty and will surely be the happier for it in the end? If I don’t seem to need help, it is because I have a better friend, even than Father, to comfort and sustain me. My child, the troubles and temptations of your life are beginning and may be many, but you can overcome and outlive them all if you learn to feel the strength and tenderness of your Heavenly Father as you do that of your earthly one. The more you love and trust Him, the nearer you will feel to Him, and the less you will depend on human power and wisdom. His love and care never tire or change, can never be taken from you, but may become the source of lifelong peace, happiness, and strength. Believe this heartily, and go to God with all your little cares, and hopes, and sins, and sorrows, as freely and confidingly as you come to your mother.”

Jo’s only answer was to hold her mother close, and in the silence which followed the sincerest prayer she had ever prayed left her heart without words. For in that sad yet happy hour, she had learned not only the bitterness of remorse and despair, but the sweetness of self-denial and self-control, and led by her mother’s hand, she had drawn nearer to the Friend who always welcomes every child with a love stronger than that of any father, tenderer than that of any mother.

This bit really stuck out to me, as I re-read Little Women this summer. It’s far more overtly religious than anything else in the book. There are references, elsewhere, to Marmee giving each girl a beautifully printed Bible to serve as their “guidebook” in life, and there’s a section where the girls play at Pilgrim’s Progress, and other references to prayer, and there are Christmas festivities. But this? This sticks out.

I’m also struck by how much more personal, and less judgmental, Marmee’s God seems than Katy’s mother’s God. The entire approach, as each mother talks with her daughter, is just so different. “I do wish I could make you love to pray, my darling child,” Katy’s mother says—and that’s about it. Katy is left feeling dour and gloomy. In contrast, Marmee leaves Jo feeling uplifted and positive about the future. Rather than leaving her to stew in “the bitterness of remorse and despair” over what her temper has wrought—Amy’s skating accident—Marmee has spent time with her giving her practical advice, and painting a way forward.

I don’t know enough about either Transcendentalism or Abigail May to know whether the infusion of religion in this section is true to life, or something added to render the book more palatable and less radical. But as I think about it, I suspect that both women—Alcott and Prentiss—were writing of their childhoods. Prentiss grew up in a fairly dour Calvinist home, and may have felt as gloomy as Katy. Regardless of whether the religious content in its particulars reflects Alcott childhood, the mood does.

Abigail May is pretty much my hero.

Anyway, this incident marks the end of the first chapter of Stepping Heavenward. What do we know so far? Katy is 16. She is headstrong and spirited, and is going through some serious spiritual angst, largely brought on by her very religious mother. She adores her mother, and grapples with some serious self-hatred. She went out without her boots and got sick for a month, she quarrels a lot with her brother, and is currently in a spat with her best friend from school, Amelia, over Amelia making friends with the new girl, Jane Underwood.

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!