Stepping Heavenward, chapter I, part 2

Last week, we covered Katy’s 16th birthday, which occurred on Jan. 15, 1831. This week, we cover the first few months of 1831. Before I jump back in to Stepping Heavenward, though, I again want to spend a few minutes on some background matter. I don’t plan to be doing this every week, but I did some digging and found some more information about Prentiss that is of interest.

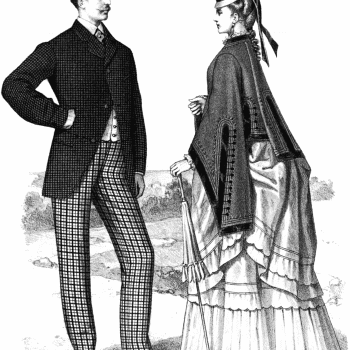

Before I get into the background information, I want to take a moment to talk about Katy’s mother. In the comments section on last week’s post several readers suggested that Katy’s mother sounds like a narcissist. Having reread the entire book, I don’t actually think this is the case. I think we need to understand both the norms of the time, and the purposes of this book.

In many ways, Katy’s mother is similar to Marmee, the mother in Little Women. Like Marmee, Katy is a maternal background presence who is always there. Like Marmee, she is someone her daughter can rely on to be there when she’s in a scrape, and, like Marmee, she is an authority figure who dispenses wisdom and advice. Of course, there’s the whole laying out a laundry list of Katy’s faults on her birthday bit. I’m not suggesting the two mothers are identical; they aren’t.

Later, we’ll going to come to a passage that will allow us to compare Katy’s mother and Marmee directly, when Katy has an interaction with her mother that is virtually identical to an exchange Jo has with Marmee, with some significant differences. In the meantime, I want to emphasize that Katy’s mother is acting within a particular evangelical subculture where calling attention to your child’s faults in order to push them along in their Christian journey was considered appropriate.

It is worth noting that Louisa May Alcott’s mother, Abigail May, raised Alcott and her sisters outside of this mainstream intentionally, eschewing corporal punishment and adhering to all manner of radical ideas about girls and women. So while we can compare the two novels and find common themes, the two also had very foundations and very different purposes.

This all brings me to my second point. After writing last week’s entry, I pulled a book off my shelf—Candy Gunther Brown’s The Word in the World: Evangelical Writing, Publishing, and Reading in America, 1789-1880. It occurred to me that Brown might mention Stepping Heavenward. I checked the index, and hit the jackpot—six straight pages on it. I want to pause for a moment to gain a better understanding of the place and position of Prentiss’ book.

Brown begins her section on Prentiss as follows:

Elizabeth Prentiss (1818-78), born in Portland, Maine, to Ann Shipman and Congregationalist revival preacher Edward Payson, was one of many nineteenth-century evangelical women who used fiction to sanctify the print market by translating doctrinal preaching into a popular cultural medium.

Brown confirms my feeling that there is something radical in the extent to which the women in Prentiss’ book formulate their own theological ideas and teach these ideas not only to each other but also to the men in their lives. What I hadn’t thought about is that the entire book is premised on this idea—it is Prentiss’ way of preaching, even though she is a woman.

When asked whether she had taken her doctrine from her father, Edward Payson, Prentiss claimed to be old enough to have the right to a theology of her own.

Unlike Debi Pearl or Lori Alexander today, Prentiss did not feel the need to justify developing and teaching of theological ideas by arguing that she was an older woman teaching younger women how to be good and pure keepers of the home and helpmeets to their husbands, as outlined in Titus 2. Prentiss had a husband and children, but was not expected to either give up her writing or, say, write only theology that was first read and approved by her husband.

In many ways, Prentiss had more freedom, as an evangelical woman living in the mid-1800s, than women in fundamentalist church communities have today.

And just what is Prentiss’ theology?

Stepping Heavenward stakes out a position distinct from Payson’s Calvinism, yet it shares the same consciousness of original sin and passion for a renewed relationship with God though faith in Jesus Christ.

In the beginning of Prentiss’ novel, it’s the Calvinism that comes through most clearly, although I’ll note a few fractures here and there, in the next few sections. As the book moves on, though, we will begin to see where Prentiss parts ways from Calvinism. Indeed, Katy ultimately ends up disagreeing with and debating individuals—including men!—who hold Calvinist ideals.

I’ve been trying to figure out where Prentiss stood on the social issues of her day—slavery, for example—because evangelicals of the antebellum period were all over the spectrum. Garrison, a radical abolitionist, was an evangelical. But then, plenty of evangelicals were strong supporters of slavery. Prentiss never mentions slavery in her book, and Brown gives us only small hints.

For example, there’s this:

In the evaluation of her 1884 biographer, Prentiss won an audience, not because she wrote anything extraordinary or subversive, but because her writings flowed “squarely in the center of a stream of evangelical preaching which made her interpretation of daily Christian life utterly familiar to a large section of churchgoing America.”

And then there’s also this:

Prentiss reserved her sharpest criticism not for her father but for contemporary novelists whom she understood to have lost sight of Christ in their fictionalization of doctrine, including Harriet Beecher Stowe in her later works such as The Minister’s Wooing (1859) and Elizabeth Stuart Phelps Ward in The Gates Ajar (1868). After reading one of the many offshoot novels inspired by Phelps, Gates Off the Hinges, Prentiss quipped that the next volume ought to be titled “There Ain’t No Gates.”

Rereading this section in Brown’s book has really reemphasized for me how many women were using fiction to make a case for their particular beliefs—about theology or society as a whole—in the mid-1800s. Whether Prentiss’ objection to Stowe’s relative radicalism extended to Stowe’s antislavery views is unclear, but clearly, Prentiss believed there were limits to how far theology should be taken. She believed she had the right to make theological interventions, but not to overturn the cart altogether. She was no left-wing evangelical radical herself.

One last quote from Brown, which neatly explains both Prentiss’ divergence from her father and her objection to writers like Stowe and Phelps, as well as the interventions she herself made:

Payson and Prentiss did not disagree about human or divine nature—doctrines that authors such as Stowe and Phelps revised—but about the salvation process. Payson’s generation of Calvinists had emphasized the doctrine of justification, exemplified by a momentous one-time conversion experience under the influence of a minister’s revival preaching. Prentiss and her peers renewed seventeenth-century Calvinism’s priority on the lifelong, gradual sanctification process; the nineteenth-century version of this doctrine heightened the role that women played in guiding spiritual as well as physical growth in the domestic circle.

With all of this out of the way, let’s return to Katy’s diary.

As you will remember from last week, Katy wrote her first entry on her 16th birthday, January 15, 1831. On January 30th, just over two weeks after her first entry, Katy writes her next entry:

Here I am at my desk once more. There is a fire in my room, and mother is sitting by it, reading. I can’t see what book it is, but I have no doubt it is Thomas A Kempis. How she can go on reading it so year after year, I cannot imagine. For my part I like something new.

Thomas à Kempis is clearly mentioned intentionally. In the next few entries Katy is going to talk a bit about what she likes to read. Noting her mother’s love of Thomas à Kempis—and at once dismissing it—gives us a standard against which to compare Katy’s own frivolous reading habits.

The name Thomas à Kempis is familiar to me, but I don’t know anything about him, so I looked him up. He lived in the late medieval period in Europe. He was German-Dutch. This was before the Reformation, so he would have been Catholic. Wikipedia says he was a member of “the modern devotion,” a spiritual movement of the time, and that he was a prior and both copied the Bible and wrote devotional booklets, which is presumably what Katy’s mother is reading.

Why would Katy’s mother be reading books by a medieval prior? I don’t think we’re meant only to know that Katy’s mother is reading devotional literature, because the mention of Thomas à Kempis feels too particular for that. Fortunately, Brown’s book fills in details we’re lacking:

[John] Wesley wrote or republished hundreds of evangelical tracts and books, beginning with Thomas à Kempis’s Imitation of Christ (1471-72)… (p. 34)

In other words, John Wesley—who founded Methodism in the late eighteenth century and had an enormous influence on American evangelicalism in the first half of the nineteenth century and beyond—not only liked Thomas à Kempis but also republished his books, including his Imitation of Christ, very likely the exact book Katy’s mother is reading.

Brown also writes (page 131) that author Elizabeth Prentiss herself “returned year after year to Thomas à Kempis’s Imitation of Christ,” among other devotional literature. (Brown adds that Prentiss “did not generally ‘like to read sermons,'” preferring instead to seek “the ‘strengthening’ food of Christian experience wherever she could find it, even culling the ‘cream’ from authors outside the evangelical canon,” including Catholic writers, which is extremely interesting.)

But this is an awful lot of time to spend on Thomas à Kempis! The point is, Katy’s mother reads and rereads devotional books that other evangelicals of her time were reading—in this particular case Thomas à Kempis—and Katy does not understand how she can stand to do it. Boring.

Moving right along!

Remember how Katy decided in the last installment to say her prayers in bed? Despite multiple readers noting in the comment section that being in bed meant one could be warm while praying instead of being out in the drafting January cold, Prentiss very clearly wants us to know that Katy should definitely not have gotten in bed to say her prayers.

That night when I stopped writing, I hurried to bed as fast as I could, for I felt cold and tired. I remember saying, “Oh, God, I am ashamed to pray,” and then I began to think of all the things that had happened that day, and never knew another thing till the rising bell rang and I found it was morning. I am sure I did not mean to go to sleep. I think now it was wrong for me to be such a coward as to try to say my prayers in bed because of the cold.

I understand Katy’s chagrin at falling right asleep, although the guilt heaped on here pretty clearly comes from Prentiss’ Calvinist upbringing. But also.

The reason Katy fell asleep forthwith is that she was coming down with a very bad illness as the result of not wearing her boots, and you would think, in retrospect, that Katy’s not spending time kneeling on her cold floor that night (this is before central heating) would be seen as a good thing.

Have a look:

I jumped up as soon as I heard the bell, but found I had a dreadful pain in my side, and a cough. Susan says I coughed all night. I remembered then that I had just such a cough and just such a pain the last time I walked in the snow without overshoes. I crept back to bed feeling about as mean as I could. Mother sent up to know why I did not come down, and I had to own that I was sick. She came up directly looking so anxious! And here I have been shut up ever since; only to day I am sitting up a little.

To her mother’s credit, it sounds like she didn’t say “I told you so.” Prentiss, though, wants to make sure the moral here is hammered in hard:

Poor mother has had trouble enough with me; I know I have been cross and unreasonable, and it was all my own fault that I was ill. Another time I will do as mother says.

Katy’s January 30th entry ends here. But, just in case we missed the lesson to be learned here, there’s a short entry from the next day:

How easy it is to make good resolutions, and how easy it is to break them! Just as I had got so far, yesterday, mother spoke for the third time about my exerting myself so much. And just at that moment I fainted away, and she had a great time all alone there with me. I did not realize how long I had been writing, nor how weak I was. I do wonder if I shall ever really learn that mother knows more than I do!

All of a sudden this song is stuck in my head:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jt50UtON8Go

If this wasn’t an evangelical book in a pseudo devotional genre, this whole “I should have listened to mom!” bit might ring a bit more true for me. I feel like I can see some of this in my own life, with my two kids, after all! “I’m cold!” my oldest will declare. “I told you you to bring your jacket,” I’ll remind her. “I didn’t realize it was going to be this cold!” she’ll respond.

But in this book—a book that sanctifies the domestic and uses fiction to preach theology—this whole “oh gosh, I should have listened to mom” bit feels a bit more pointed. To be fair, though, we’re given to think very little of Amelia’s mom, later on, so maybe it’s not that moms in general know everything, but that Katy should know enough of her mother to respect her judgement.

I really did mean to go on here, but I find this post grown long already. This review series is going to be a bit different from others we’ve looked at, but I’m going to try to keep things moving at a fast enough clip to keep it interesting—and there’s a lot going on to keep up with.

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!