Stepping Heavenward, chapter V

Having broken things off with Charlie, Katy has dedicated herself to doing good. Surely loving God means doing good, after all. Katy is just not always sure what good she can do.

On her mother’s suggestion, Katy has taken a Sunday school class.

There are twelve dear little things in it, of all ages between eight and nine. Eleven are girls, and the one boy makes me more trouble than all of them put together. When I get them all about me, and their sweet innocent faces look up into mine, I am so happy that I can hardly help stopping every now and then to kiss them.

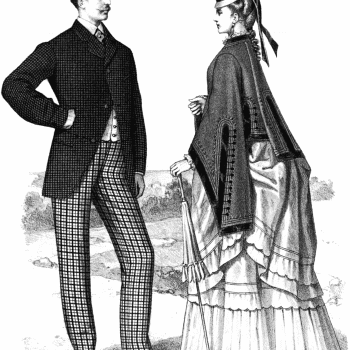

Kissing all the children probably wouldn’t go over all that well today, but the emphasis on the children’s sweetness and innocence is in keeping with a change that was taking place within the middle class at this time. Whereas children had previously been seen as depraved and in need of discipline and training, children were increasingly seen as innocent and pure. And while childhood had previously been a period to hurry children through—lest they die along the way—the middle class increasingly saw childhood as a special period to be celebrated.

While Katy is teaching this Sunday School class, an incident occurs that will later be important. Katy has her first encounter with the man she will marry (sorry, spoilers!).

APRIL 27.-This morning I had my little flock about me, and talked to them out of the very bottom of my heart about Jesus. They left their seats and got close to me in a circle, leaning on my lap and drinking in every word. All of a sudden I was aware, as by a magnetic influence, that a great lumbering man in the next seat was looking at me out of two of the blackest eyes I ever saw, and evidently listening to what I was saying. I was disconcerted at first, then angry. What impertinence. What rudeness! I am sure he must have seen my displeasure in my face, for he got up what I suppose he meant for a blush, that is he turned several shades darker than he was before, giving one the idea that he is full of black rather than red blood. I should not have remembered it, however-by it-I mean his impertinence–if he had not shortly after made a really excellent address to the children. Perhaps it was a little above their comprehension, but it showed a good deal of thought and earnestness. I meant to ask who he was, but forgot it.

It’s so … random. But, okay. I guess.

Oh! Guess what! Katy has a new friend. Clara Ray. They have parties and excursions—“Clara Ray and all her set”—and Katy is invited along. This is good! Katy needs friends!

Oh wait. Oh crap. Katy starts feeling guilty about filling her time with “picnics, drives, parties, etc.,” and finds that her prayers have become “dull and short.” And then Clara tells Katy that “the girls think me reckless and imprudent in speech,” so Katy dumps her and her set.

So much for making new friends.

Katy grows morose.

All my pleasures are innocent ones; there is surely no harm in going to concerts, driving out, singing, and making little visits! But these things distract me; they absorb me; they make religious duties irksome. I almost wish I could shut myself up in a cell, and so get out of the reach of temptation.

And then, later:

I see that if I would be happy in God, I must give Him all. And there is a wicked reluctance to do that. I want Him-but I want to have my own way, too. I want to walk humbly and softly before Him, and I want to go where I shall be admired and applauded. To whom shall I yield? To God? Or to myself?

Eep.

So Katy goes to Dr. Cabot, and asks if it’s okay for her to play and sing in company “when all I do it for is to be admired.” This has become a standard fare of this book, these conversations with Dr. Cabot. As he usually does, Dr. Cabot leads Katy along to a specific conclusion. He tells her that refusing to sing in company would not eliminate her “love of display,” but that it would punish her friends, by depriving them of the pleasure of her singing.

“No child, go on singing; God has given you this power of entertaining and, gratifying your friends. But, pray without ceasing, that you may sing from pure benevolence and not from pure self-love.”

But oh dear! Disaster strikes! There was a shakeup in the Sunday School department and Maria Perry has taken half of Katy’s students! Whatever will Katy do!

“[Y]ou have taken my very best children-the very sweetest and the very prettiest. I shall speak to Mr. Williams about it directly.”

“It is just as pleasant to me to have pretty children to teach as it is to you. Mr. Williams said he had no doubt you would be glad to divide your class with me, as it is so large.”

Um guys. The children were there when they were talking. That’s the reason Katy doesn’t go directly to Mr. Williams—the children are all there and she must begin teaching. Awkward.

Seriously, what is this emphasis on which children are prettiest? It’s just so disturbing and gross. I’m reminded of this sculpture in Denver, completed in the 1880s, where the artist visited 5,000 girls across the city in search of the most beautiful and angelic face, finally choosing six-year-old Ella Catharine Matty. Of course, who are we to speak! We still have beauty pageants for toddlers today. But really, what is Katy communicating to the students she’s left with? Does she treat them differently because they’re not as pretty?

But don’t worry! All is quickly solved! The next day, Mr. Williams comes by to tell Katy that she will have all of the children back again the next week.

All the mothers had been to see him, or had written him notes about it, and requested that I continue to teach them. Mr. Williams said he hoped I would go on teaching for twenty years, and that as fast as his little girls grew old enough to come to Sunday-school he should want me to take charge of them.

Well that’s. Convenient?

Katy feels bad for “the display I made of myself to Maria Perry” and wishes she could “bridle my unlucky tongue.” But she is, apparently, good with children.

I wonder that Katy does not consider becoming a teacher, at least until she marries, like Laura does in the Little House books. But then, this book was published in 1869 and this bit is ostensibly set in the 1830s, and Laura became a teacher in the 1870s or 1880s; women didn’t dominate the teaching profession in the 1830s the way they came to later. Still, when her family found itself in reduced circumstances, Katy switched from “Mr. Stone’s school” to “Miss Higgins’ school,” so clearly women in the area could teach, and Katy is familiar with the concept. Perhaps women of Katy’s class did not teach?

Here we skip some months again, clear up to January, 1835. Katy is now twenty. There has been no mention of beaus, or of any attempt on her mother’s part to set her up with one.

I have begun to visit some of mother’s poor folks with her, and am astonished to see how they love her, how plainly they let her talk to them. As a general rule, I do not think poor people are very interesting, and they are always ungrateful.

Well that’s … lovely.

Prentiss describes several of these visits—or rather, Katy does in her journal—and Katy finds herself much impressed by her mother’s patience. At one point, after visiting Susan Green, who does nothing but talk, Katy wonders aloud to her mother what good the visit did.

“Why the poor creature likes to show off her bright carpet and nice bed, her chairs, her vases and her knick-knacks, and she likes to talk about her beloved money, and her bank stock. I may not have done her any good; but I have given her a pleasure, and so have you.”

“Why, I hardly spoke a word.”

“Yes, but your mere presence gratified her. And if she ever gets into trouble, she will feel kindly towards us for the sake of our sympathy with her pleasures, and will let us sympathize with her sorrows.”

I confess this did not seem a privilege to be coveted. She is not nice at all, and takes snuff.

As I’ve mentioned before, I’m fairly certain that Katy’s comments like this are designed primarily to keep the reader interested—it makes this book different from the dry volumes of sermons to which readers looking for religious fare might otherwise be directed.

We went next to see Bridget Shannon. Mother had lost sight of her for some years, and had just heard that she was sick and in great want. We found her in bed; there was no furniture in the room, and three little half-naked children sat with their bare feet in some ashes where there had been a little fire. Three such disconsolate faces I never saw.

This visiting of the poor is another common thread between this book and Alcott’s Little Women. This scene makes me think of the very beginning of Little Women, when Marmee goes out early one Christmas morning and comes home to ask her girls to make a sacrifice:

“Not far away from here lies a poor woman with a little newborn baby. Six children are huddled into one bed to keep from freezing, for they have no fire. There is nothing to eat over there, and the oldest boy came to tell me they were suffering hunger and cold. My girls, will you give them your breakfast as a Christmas present?”

The girls agree, with only a little bit of reluctance, and pack up their breakfast. Together, they walk in a procession to the home of the Hummel family. Again, from Little Women:

A poor, bare, miserable room it was, with broken windows, no fire, ragged bedclothes, a sick mother, wailing baby, and a group of pale, hungry children cuddled under one old quilt, trying to keep warm.

How the big eyes stared and the blue lips smiled as the girls went in.

… Hannah, who had carried wood, made a fire, and stopped up the broken panes with old hats and her own cloak. Mrs. March gave the mother tea and gruel, and comforted her with promises of help, while she dressed the little baby as tenderly as if it had been her own. The girls meantime spread the table, set the children round the fire, and fed them like so many hungry birds, laughing, talking, and trying to understand the funny broken English.

“Das ist gut!” “Die Engel-kinder!” cried the poor things as they ate and warmed their purple hands at the comfortable blaze. The girls had never been called angel children before, and thought it very agreeable… That was a very happy breakfast, though they didn’t get any of it. And when they went away, leaving comfort behind, I think there were not in all the city four merrier people than the hungry little girls who gave away their breakfasts and contented themselves with bread and milk on Christmas morning.

“That’s loving our neighbor better than ourselves, and I like it,” said Meg, as they set out their presents while their mother was upstairs collecting clothes for the poor Hummels.

Katy finds she likes it too.

Mother sent me to the nearest baker’s for bread; I ran nearly all the way, and I hardly know which I enjoyed most, mother’s eagerness in distributing, or the children’s in clutching at and devouring it. I am going to cut up one or two old dresses to make the poor things something to cover them.

But Katy has some lessons to learn.

One of them has lovely hair that would curl beautifully if it were only brushed out. I told her to come to see me to-morrow, she is so very pretty.

Seriously, what is it with this focus on pretty children?!

Well. It goes very badly. Very badly indeed.

JAN. 20.-The little Shannon girl came, and I washed her face and hands, brushed out her hair and made it curl in lovely golden ringlets all round her sweet face, and carried her in great triumph to mother.

“Look at the dear little thing, mother!” I cried; “doesn’t she look like a line of poetry?”

“You foolish, romantic child!” quoth mother. “She looks, to me, like a very ordinary line of prose. A slice of bread and butter and a piece of gingerbread mean more to her than these elaborate ringlets possibly can. They get in her eyes, and make her neck cold; see, they are dripping with water, and the child is all in a shiver.”

So saying, mother folded a towel round its neck, to catch the falling drops, and went for bread and butter, of which the child consumed a quantity that, was absolutely appalling. To crown all, the ungrateful little thing would not so much as look at me from that moment, but clung to mother, turning its back upon me in supreme contempt.

Moral.-Mothers occasionally know more than their daughters do.

Oy. Yeah, that went well.

Why did Katy get the girl’s hair wet in the first place? I can see brushing it out, and sure, with curly hair it can help to add some moisture, but wet to the point of dripping? That’s wholly unnecessary. It’s January. Jeez, Katy. At least give her some food to eat while you do her hair, you already know she doesn’t have much food at home. This shouldn’t be that hard.

Is Katy’s mother’s comment meant to imply something about the child’s social class? And what’s with the constant referral to children as “it”? This isn’t the first time. When did that change, in literature? I’m fairly certain it’s pretty taboo to refer to a child as “it” today.

Anyway! Katy seems to recognize that she messed up. Is this episode meant to be an indictment of Katy’s focus on how pretty individual children are? Or something more limited?

Guess what! I took us through more quickly and we finished a whole chapter! Going forward, I’m hoping to cover one chapter each week, to keep us from getting bogged down.

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!