“THE UNIVERSE IS BASED ON THE SUBJECTION OF WOMAN.”

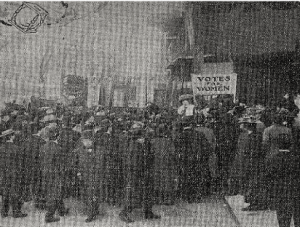

The woman suffragists held their third and largest open-air meeting under less-than-desirable circumstances on January 14, 1908. An icy wind whistled relentlessly over Madison Square, yet the suffragists in charge were out at least a dozen strong, the largest turnout yet.

“Sure, th’ women must want th’ vote bad, t’ spout f’r it on sthrate corners such a day.”

That was the opinion of one-half the audience at the open air suffragette meeting. That half was a small man with a skeptical eye. But the other half, being a woman, thought differently.

“If you waked up some mornin’ and found this country bein’ run by one sex, an’ that sex not yours, wouldn’t you be after spoutin’, too?”

“Mrs. Cobden Sanderson Addresses Men in Madison Square.”

The audience grew larger as the meeting went on. At five minutes to 11 o’clock (11 a.m. being the hour announced) it looked as if there would be no one to receive the bolts, nor any to hurl them for that matter. Madison Square East was empty, save for an icy blast, two policemen, and a shivering man with a portable stand. But precisely at 11 Mrs. Cobden-Sanderson appeared, large and determined, and Mrs. B. Borrmann Wells, a smaller but equally determined woman. Then came Miss Maud Malone, of Harlem, bearing aloft a placard which said:

“Votes for women! Sign the petition to amend the constitution, whereby women will be enfranchised!”

The next arrival was Bolton Hall, in a “stovepipe” hat, so conspicuously respectable that the two policemen heaved a sigh of relief and dropped back. Then a small army of photographers descended upon the scene, and two messenger boys stopped to see what was happening. Cheered by the sight, the speakers marched across the street to the place where the shivering man was nursing the portable stand. Malone led the way with her banner, which she planted, beside the stand with such manful energy that, if it had not been for her saying that “it did not hang right,” and “wouldn’t somebody lend [her] a pin,” the flavor of emancipation would have been complete.

Irvine, who volunteered to open the ball, struck a spark of enthusiasm in the crowd that began to gather.

“I want my wife to vote!” he announced.

“Ah, ain’t he the jewel of a husband!” sighed the woman who had argued with the skeptical man.

“Men declare that virtue and purity reside in woman, yet they are unwilling to allow this virtue to express itself in Legislature,” Irvine continued. “Give women the vote!”

“Ah, sure, there’ll niver be be civilization till we git it,” said the woman fervently.

“Isn’t it wonderful,” the speaker said, “to see these delicate women coming out this cold January morning to convince the passerby, whether they have large brains or small ones, or—” and he looked severely at the gathering crowd of men, “—no brains at all.”

“Oh the suffragettes have brains alright,” opined a man in the rear, “only they don’t use ‘em right.”

Wells mounted the stand and the crowd listened attentively, whether from interest or the novelty of the situation.

“I met a certain self-satisfied man the other day,” she began. “He said to me, ‘Why, what would you do with the vote if you had it? You’d take it home and make pie of it, I suppose?’

“‘And what have you done with the vote?’ I asked him. ‘You’ve taken it to Albany and made hash of it.”

Bolton Hall, the next speaker, was evidently aching to talk about single tax, but restrained himself and proceeded to demolish the argument that women oughtn’t vote because they don’t fight.

“It is false to say that women don’t fight,” he said ardently. “False to say that they don’t fight with physical force. They do!”

“Ah, true for you. They do!” shouted a man with a black eye and two deep scratches on his right cheek.

“War,” said Hall, with a hasty effort to get away from the personal flavor, “it is becoming more and more a matter of brains, and I feel sure that, given the chance, women could pursue that sort of warfare as cleverly, and as inexorably as men.”

Harriett Keyser took the stand. “There has been a lot of talk lately about open-air meetings not being respectable,” she said, “but I consider the good cause ensures the respectability. We women are tired of being disfranchised auxiliaries.”

Mrs. Cobden Sanderson, who was to sail for England, made a farewell speech. She said some things about woman suffrage in New Zealand, which stirred the wrath of a man in the fringe of the crowd.

“No petticoat government for me!” he called tauntingly.

“I’m sorry to hear a man say that,” replied the speaker. “But the vote isn’t kept from us by men. It’s kept from us by the indifference of women of the upper class. They have all they want, say they. Yes, and they have more than they need they are prisoners of luxury. I don’t look to the rich for help in this reform, I look to the common people.”[1]

SUFFRAGE & FEMINISM

The interests of the Suffragists and Feminists, though overlapping in many ways, were not the same movements. “An essential difference between ‘Feminism’ and ‘Suffragism,’” writes early Feminist, W.L. George, “is that the Suffrage is but part of the greater propaganda; while Suffragism desires to remove an inequality, Feminism purports to alter radically the mental attitudes of men and women.”[2] Feminism and Socialism, likewise, had complimentary traits, such as the term “patriarchy.” It had its origins in American social-theorist, Lewis Henry Morgan’s 1871 ethnological treatise, Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family. In this work Morgan states that there are 15 stages of familial/civilizational development ranging from the lowest, “Promiscuous Intercourse,” to the highest “The Overthrow of the Classification System,” with the penultimate stage of civilizational development being “Patriarchy.”[3] This work was expounded upon by the Socialist, Fredrich Engels, in a work (posthumously published in 1884) titled The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State: in the Light of the Researches of Lewis H. Morgan. Engels states: “Man’s […] unlimited rule was emphasized and endowed with continuity by the downfall of matriarchy, the introduction of patriarchy, and the gradual transition from the pairing family to the monogamic family.” [4] It the summer of 1888, the Feminist writer Mona Caird popularized the term “patriarchy” based off of Engel’s theories.[5] “The woman of the nineteenth century finds the old shells and sheaths of a decaying patriarchal system drawn away from her,” Caird states, “while at the same time she is exposed, or liable to be exposed, to the full blast of the competitive tempest in which modern life is passed, almost from the cradle to the grave.”[6]

Leading American Feminists weighed in on Caird’s essay. “Marriage,” said Matilda Joselyn Gage, “for woman, is a slavish institution.” Grace Greenwood believed that marriage was “woefully out of harmony with the spirit of [the] age,” while Ella Wheeler Wilcox believed that “the system of marriage [was] alright; it [was] the abuse of it that [they] deplored.”[7] By the first decade of the twentieth-century, confidence in marriage had soured considerably among Feminists. W.L. George writes:

With marriage [Feminists] are per most concerned. Though they not in the main prepared to advocate free union, they are emphatical arrayed against modern marriage, which they look upon as slave union. The somewhat ridiculous modifications of the marriage service introduced by a few couples in America and by one in England in which the word “obey” was deleted from the bride’s pledge, can be taken as indicative of the Feminist attitude. Their grievances against the home, against the treatment of women in the trades, are closely connected with the marriage question, for they believe that the desire of man to have a housekeeper, of woman to have a protector, deeply influence the complexion of unions which they would base exclusively upon love, and it follows that they do not accept as effective marriage any union where the attitudes of love do not exist. For them who favor absolute equality, partnership, sharing of responsibilities and privileges, modern marriage represents a condition of sex slavery into which woman is frequently compelled to enter because she needs to live, and in which she must often remain, however abominable the conditions under which the union is maintained, because man, master of the purse, is master of the woman. Generally, then, the Feminists are in opposition to most of the world institutions. For them the universe is based upon the subjection of woman.

In the main, Feminists are opposed to indissoluble Christian marriage. Some satisfaction has been given to them in a great many states by the extension of divorce facilities, but they are not content with piecemeal reform such as has been carried out in the United States, for they realize quite well that divorce cuts both ways, and that it is not satisfactory for a wife to be married in one state, and divorced under a slack law in another. Indeed I believe that one of the first Feminist demands in America would be for a federal marriage law. But alterations in the law are minor points by the side of the emotional revolution that is to be engineered […]

Personally, I am inclined to believe that the ultimate aim of Feminism with regard to marriage is the practical suppression of marriage and the institution of free alliance. It may be that thus only can woman develop her own personality, but society itself must so greatly alter, do so very much than equalize wages and provide for all, that these ultimate ends very distant. They lie beyond the de cease of Capitalism itself, for imply a change in the nature of human being which is not when we consider that man has a great deal since the Stone Age, is still inconceivably radical […]

One feature manifests itself, and that is a change of attitude in woman with regard to the child. Indications in modern novels and modern conversation are not wanting to show that a type of woman is arising who believes in a new kind of matriarchate, that is to say, in a state of society where man will not figure in the life of woman except as the father of her child. Two cases have come to my knowledge where English women have been prepared to contract alliances with men with whom they did not intend to pass their lives—this because they desired a child. They consider that the child is the expression of the feminine personality, while after the child’s birth, the husband becomes a mere excrescence […]

One of the most profound changes will, I think, appear in sex relations. The “New Woman” as we know her today, a woman who is not so new as the woman who will be born of her, is a very unpleasant product; armed with a little knowledge, she tends to be dogmatic in her views and offensive in argument. She tends to hate men, and to look upon Feminism as a revenge; she adopts mannish ways, tends to shout, to contradict, to flout principles because they are principles; also she affects a contempt for marriage which is the natural result of her hatred of man.[8]

The “Progressives” of the Progressive Era, as the name might suggest, were concerned with its antonym, “Decadence.” In fact, “Decadence” was the title of a lecture by Arthur Balfour (former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom) in January 1908.[9] (Rev. Percy S. Grant, naturally, also wrote a great deal on the topic.)[10] This theme appeared in the constellation of topics regarding “social ills.” The role of women is society was very much discussed, as the State was encroaching into domestic affairs like marriage and divorce. This interested the Socialists, and it was said: “The greatest barrier against the advance of socialism in property is the institution of the family. The family and private property are, in their judgment, so intimately related that property cannot be socialized until the institution of the family is socialized also.”[11] Some feared that human societies, like analogous systems in the animal kingdom, were at risk of creating a “third sex” by manipulating ancient gender roles. “Human society like the societies of the social insects might evolve a neuter sex originally female very highly individuated like the worker bee, which has paid the all-but-inevitable price of such very high individuation in virtual or actual sterility.”[12] This view reflected the common belief that “the advanced woman is a third sex possessing neutral characteristics and indifferent if not hostile to marriage and maternity.”[13]

PEOPLE OF THE UNDERWORLD

I. INTERCOLLEGIATE SOCIALIST SOCIETY.

II. THE CRY OF PEONAGE.

III. MUCKERS.

IV. GALLAGHER’S HELL.

V. PUNK.

VI. SOUDAN.

VII. BOWERY.

VIII. “IT IS A BETTER FLAG THAN THE AMERICAN FLAG.”

IX. PENETRATING THE ASCENSION.

X. “THE UNIVERSE IS BASED ON THE SUBJECTION OF WOMAN.”

XI. PROGRESSIVE WOMAN SUFFRAGE UNION.

XII. THE CHRISTIAN SOCIALIST FELLOWSHIP.

XIII. THE ERUPTION OF THE END.

SOURCES:

[1] Mrs. Cobden Sanderson Addresses Men in Madison Square. 1908. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/rbcmiller001147/.

[2] George, W.L. “Feminist Intentions.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXII, No. 6 (December 1913): 721-732.

[3] Morgan, Lewis Henry. Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family. The Smithsonian Institute. Washington, D.C. (1871): 480.

[4] Engels, Friedrich. The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State. Charles h. Kerr & Company Co-Operative. Chicago, Illinois. (1902): 196-197.

[5] Fillingham, Lydia Alix. “’The Colorless Skein of Life’: Threats to the Private Sphere in Conan Doyle’s A Study in Scarlet.” ELH. Vol. LVI, No. 3 (Autumn 1989): 667-688.

[6] Caird, Mona. The Morality of Marriage And Other Essays On The Status And Destiny Of Woman. George Redway. London, England. (1897): 69.

[7] O’Dow. Betsy. “Believe In Marriage.” The Los Angeles Evening Express. (Los Angeles, California) October 20, 1888.

[8] George, W.L. “Feminist Intentions.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXII, No. 6 (December 1913): 721-732.

[9] “[Decadence] attacks, or is alleged to attack, great communities and historic civilizations: which is to societies of men what senility is to man, and is often, like senility, the precursor and the cause of final dissolution.” [Belfour, Arthur James. Decadence: Delivered At Newnham College, January 25, 1908. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, England. (1908): 6.]

[10] Grant writes: “With the growth of industrialism, cities must expand. In the country farms are deserted; in the city, mush room apartment-houses spring up. The man whose father followed the plough, must spend his days on a bookkeeper’s stool and breathe close, city air. A majority of the men and women of the United States will soon live in tenement-houses. The cradle of the future American citizen will be the tenement. Our cities are not only filled from our abandoned farms with people who for generations have been used to the vigor of country labor; our cities are filled with aliens. We are crowding the tenements with foreigners. The American farmer’s boy is trying to breathe in the devitalized air of the city, and the European peasant is trying to keep his health in America, Class and race acclimatization are going on at once. The farmer is bent upon becoming a factory or mercantile unit; the foreigner hastens to become an American. This is serious business. If you know any mill town full of foreigners, you have mourned over the deterioration of physique in the second generation. American food, hot summers, cold winters, stuffy tenements play the mischief with ruddy, beefy Englishmen or Irishmen or whom you will. I have been repeatedly shocked to find girls of sixteen among cotton operatives with full sets of false teeth.” [Grant, Percy Stickney. “Physical Deterioration Among The Poor In America And One Way Of Checking It.” The North American Review. Vol. 184, No. 608 (February 1, 1907): 254-267.]

[11] McConnell, Ray Madding. “The Ethics Of State Interference In The Domestic Relations.” International Journal Of Ethics. Vol. XVIII, No. 3 (April 1908): 363-374.

[12] Saleeby, C.W. “The Obstacles To Eugenics.” The Sociological Review. Vol. II, No. 3 (July 1909): 228-240.

[13] Atkinson, Mabel. “The Feminist Movement And Eugenics.” The Sociological Review. Vol. III, No. 1 (January 1910): 51-56.