A recent opinion piece in the New York Times bears the intriguing headline: “Super People.” No, James Atlas is not writing about recent superhero movies or about medical efforts to sustain life. The “super people” that concern Atlas are the young people, in the effort to get into high-ranking colleges and graduate schools, have become extraordinary. These super people are represented by recent winners of a prestigious fellowship:

It’s a select group to begin with, but even so, there doesn’t seem to be anyone on this list who hasn’t mastered at least one musical instrument; helped build a school or hospital in some foreign land; excelled at a sport; attained fluency in two or more languages; had both a major and a minor, sometimes two, usually in unrelated fields (philosophy and molecular science, mathematics and medieval literature); and yet found time — how do they have any? — to enjoy such arduous hobbies as mountain biking and white-water kayaking.

In response to such achievements, Atlas asks:

In response to such achievements, Atlas asks:

Has our hysterically competitive, education-obsessed society finally outdone itself in its tireless efforts to produce winners whose abilities are literally off the charts? And if so, what convergence of historical, social and economic forces has been responsible for the emergence of this new type? Why does Super Person appear among us now?

No simple explanation suffices to answer these questions. Super People are a result, in part, of the insane competition for acceptance into top educational institutions. They are present as a result of the Baby Boomer obsession to produce highly successful children who become highly successful adults. According to Atlas, Super People are usually the offspring for well-to-do parents, parents who can invest both time and money in giving their children exclusive life experiences, the kinds of experiences that make admissions offices take notice.

Atlas sees social risks in the elevation of upper-class super people over the masses. Yet he’s also impressed that, along the way, some of these superkids do good things: “When I read about a student who has worked at a mental health clinic in Bolivia or founded a farmers’ market in a low-income neighborhood in Washington, I’m impressed. (All we did in college, I seem to recall, is smoke dope and play pool.)”

Yet, Atlas also shows concern for the super people. He concludes his article:

Yet, Atlas also shows concern for the super people. He concludes his article:

In the end, the whole idea of Super Person is kind of exhausting to contemplate. All that striving, working, doing. A line of Whitman’s quoted by Dr. Bardes in our conversation has stayed with me: “I loaf and invite my soul.”

Isn’t that where the real work gets done?

I do wonder what will happen to the souls of the super people. My fear is that their souls will be repressed, ignored, perhaps warped and wounded. Then, I wonder what will happen to a world that will increasingly be led by super people with such souls. Will it be a world of compassion and mercy, or of accomplishment and exhaustion? Will super people thrive as spouses, parents, neighbors and friends? Or will they be too busy, not to mention too depressed, to contribute to the common good?

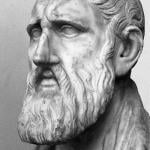

I’m reminded of a man who once sought to make a super person. In many ways, he succeeded. But, if he were with us today, I expect Dr. Viktor Frankenstein might have some sage words of warning for us. Sometimes, in our efforts to create super beings, we end up making monsters.