We’re returning to our occasional series of posts on work and vocation (linked at the bottom of this post) in Christian history by Faith and Work Channel senior editor and Christian History magazine senior editor Chris Armstrong. Enjoy!

We’re returning to our occasional series of posts on work and vocation (linked at the bottom of this post) in Christian history by Faith and Work Channel senior editor and Christian History magazine senior editor Chris Armstrong. Enjoy!

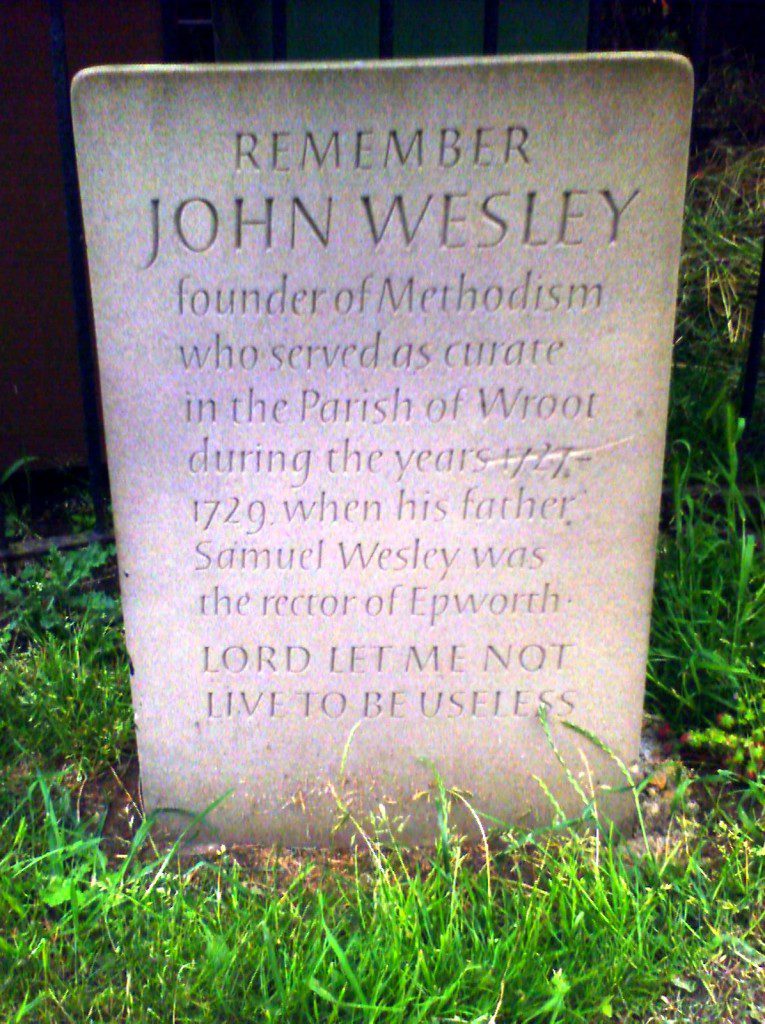

It is well known that early Methodism flourished most among the new working and middle classes – the artisans and entrepreneurs who were rising up above their formerly lowly status in the ancestral class system, in which for example Anglican priests were members of the upper class, and wielded disproportionate social as well as religious authority in the towns. It was the newly discovered mobility that allowed them to rise through industry, frugality, and investment of their time, talents, and treasures that also allowed them to question and challenge the Anglican religious establishment. Such people naturally gravitated to the fervent, warm-hearted, and freeing message of Wesley’s “born-again” religion and its free, democratic organization in small groups and mutual aid societies.

Methodism itself was in many ways entrepreneurial, and so it shouldn’t surprise that it enjoyed good relations with business such as the mining companies of Cornwall. Many of Wesley’s early converts were miners and other workers. The Wesleyan message, meetings, and organizations gave confidence to the people working in the mining businesses, and helped those who led the businesses to do so in ways that made their communities more healthy. Numerous mine captains were also Methodist preachers who communicated to their communities the powerful messages of respectability and self-improvement, thus helping to ensure that Methodism became the most relevant religious institution for laborers and the working class – far more so than the Established Church of England. Through their religion of social as well as personal holiness, Wesleyans found ways to create meaningful and rewarding work that helped to ensure that community needs were met.

Within a few short decades of its introduction in this country, Methodism became the most dominant social organization on the landscape of 19th-century America, and a key part of the “market revolution” that changed this nation’s economic landscape. Thrift, sobriety, hard work, education, a willingness to delay gratification and invest—all of these made Methodists good workers who flourished in the new industrial economy, and within two generations of arriving on American shores, Methodists were building glorious cathedrals in the great cities of their new home. When American Methodist Bishop Matthew Simpson published his 1,000-page Cyclopedia of Methodism in the mid-1870s, many of the figures profiled in its pages were businessmen—a class of people for whom he clearly had the greatest respect.

Then the hugely influential Wesleyan holiness movement burst onto the scene, first in Orange Scott’s 1840 movement, then in the Free Methodist Church, and then in the mid-1860s, through the genteel, middle-class New York City parlor meetings of Methodist laywoman Phoebe Palmer and a small circle of other leaders. Later the branches of the holiness movement that emerged from this third wave would decide, like the first two, that Methodists were becoming too comfortable in their middle-class respectability and ignoring the plight of the poor – also a legacy of John Wesley.

They turned against such rigid class-separating practices as renting the choice pews at the front of the church to wealthy community members and (more famously) the keeping of slaves. But none of that amounted to a turning away from the capitalist system of free enterprise. Rather, it indicated a deep commitment, inherited from Wesley himself, to address the social ills that sometimes arose from unchecked industrial growth, as well as the unscrupulous greed of some at the top of the capitalist heap. Methodism, like Puritanism before it, both fostered industry and entrepreneurship and sought to act as the Christian conscience of the marketplace.

Much more could be said about this influential Methodist and Wesleyan stream – but this will have to do for now. I hope you can see the legacy – both biblical and historical – on which we can build today in presenting a solid theology of work, vocation, and economics.

Originally published at Grateful to the Dead.

Previous posts in this series:

- Getting the beginning and end of the story right

- We were made to work

- Jesus the incarnate worker God’

- A brass-tacks, real-world theology of work and vocation

- Early Christianity and everyday work

- The contemplative contribution

- Luther on ordinary work and vocation

- Calvinists, Puritans, and the Wesleyan response

Image: “Wesley,” Nick Richards.