Almost eleven months ago, as COVID began to take over, I wrote of how the disease was forcing on the world something it had not taken for a long time: a sabbath. Then, last summer, as it looked like we were in it for a longer haul, I began to wonder if the commitment to stability of life in a monastery had anything to teach us.

Now, we are coming up on almost a year in this monastic holding pattern. In a little more than five weeks, it will be March 11, 2021: it’s on March 11, 2020 that the slow drumbeat of closures and CDC recommendations suddenly, at least to me, seemed to hit all at once and make everything in the U.S. shut down. The last normal thing I did, if you set aside a certain amount of extra handwashing, was travel to a conference in Kansas City from March 5-8; on the way back I wrote a blog post on just-in-time deliveries which, almost as I finished it, became a relic of the Before Times. I haven’t been out of the state of Kentucky since then. I didn’t even leave my county between March 9, 2020 and the middle of June.

Things and practices which we adopted in the hopes that they would be short stopgap measures have become part of our daily lives. Things which we used to do without a second thought now provoke nostalgia or anxiety when we think of them – or both. And lately, as I contemplate all this, I have been thinking of Thomas Merton.

Merton, for those of you who don’t know, was a Trappist monk at the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani, a monastery not far from where I live, and became one of the most famous spiritual writers of the 20th century. There’s plenty out there if you Google him: the most responsible and least sensationalist website to learn more is probably the Merton Center in Louisville. He entered the monastery in the 1940s and sometime in the 1950s began agitating to live as a hermit on the grounds. Monastic hermits go back all the way to the early centuries of the church, but the Trappists were not an eremitic order (the official word for a religious order that supports its monks living as hermits). Nevertheless, Merton prevailed and lived in a hermitage at Gethsemani for three years (1965-1968), until he died in what most probably was an unfortunate accident on a trip to Thailand to speak at a monastic conference.

Being a hermit is hard. Merton certainly found it so. He liked being famous. (I love Merton, but I am not above criticizing him, either.) He seems to have been a tremendous extrovert, and one of his most famous passages describes a spiritual experience of love for his fellow humans that occurred, not in solitary prayer, but in the middle of a crowd in downtown Louisville. (Bonus: the best poem written about this event ever is here.)

Even before he was a hermit, Merton had frequently requested to go places and speak, and had wrestled with his abbot about how much time to spend on the writings which, while benefitting millions, also stroked his own ego; the only reason he died in Thailand and not in his hermitage is because he had begged a new, and more relaxed, abbot to go on the trip. It’s fairly well documented at this point that while living in the hermitage Merton, who was allowed to leave the monastery for medical appointments (and who had many ailments) fell in love with one of the nurses that was treating him; she was 19 and he was in his 50s. They definitely corresponded, and may have done more; he wrote a series of poems for her.

What, you may ask, does any of this have to do with COVID? Well, being a hermit is hard. It was hard, as Merton’s story shows, even for a man who had vowed to devote his life to living in a religious enclosure, desired and felt called to find deeper intimacy with God in silence, and had the support of his superiors and colleagues and the affirmation of his belief system. Why should we assume it would be any easier for any of the rest of us? Especially since I think probably 95% of the people who have become hermits by virtue of COVID are not actually called to the eremitic life. I’m an introvert who has worked from home for almost a decade before COVID, and I am going stark raving bonkers over here.

And yet, all I hear from many places is that I must hold on and stay the course. I hear that the end is coming. It is always just around the corner. And yet, every time it seems the end is near, another problem arises. Lately, even as the hope has dawned of hundreds of my Facebook friends getting vaccinated, of a football field’s worth of vaccines being administered in Lexington, KY, of a steep drop in national infection rates, the story emerges of the new variants.

So, we are told, we must continue to be vigilant. We must continue to stay the course. We must continue to hold on, wear our masks, social distance, talk to people on screens, and abstain from almost everything that makes life actually worth living, from Hamlet to haircuts.

And yet, allowing for the fact that people have been known to sanitize their lives and thoughts on social media, so many people I know seem so calm about this continued hermitage living. For a while a meme was circulating that asked people why they were complaining when their grandparents had to fight in World Wars and all they were being asked to do was hang out at home and watch Netflix. Eventually someone noted that humans are actually not designed to stay home all day in the middle of a cultural and political dumpster fire and watch Netflix. It causes trauma. Lots of trauma. Where are the football fields full of grief counselors?

I am not an anti-masker. I regret that masking has become politicized. I don’t want to die, nor do I want my elderly relatives or our frontline workers or teachers to die. I don’t want anyone to die ever, really. But I sympathize quite strongly with the feeling that living as we are living is NOT NORMAL, and I believe that the way to get cooperation from people in a time of lack of normalcy is not to stigmatize them for wanting to be normal, but to say out loud, often, that wearing a mask can be profoundly uncomfortable and awkward even though for 99% of us it does not actually damage our health, that social distancing from everyone all the time goes against deep-seated human developmental needs, and that we are all going stir crazy up in this hermitage and we don’t really want to stay.

Only when we actually acknowledge how hard this is can we truly ask each other to do the hard things and provide the support necessary to help each other do the hard things.

I think Merton would have agreed.

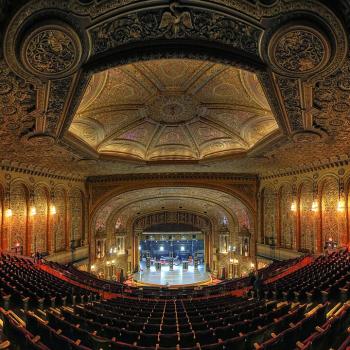

Image: Merton’s hermitage by Bryan Sherwood on Flickr under a CC 2.0 BY license. You may enjoy many of Sherwood’s pictures of Gethesmani, which you can see by going here.